due to the animals having been brought ovet in a boat-load of earth from Morven,

an explanation I cannot agree with. Moles are admirable swimmers, and could

easily have swum across the short sea passage between the mainland and Mull. In

the same way, by swimming, they probably reached the Island of Ulva, where they

also exist. In all the other islands of the Outer and Inner Hebrides the Mole is at

present unknown, as also in the Orkneys, Shetlands, and in Ireland.

Some writers attribute the earliest existence of this species in Britain to the

beginning of the Pleistocene epoch, but there is strong evidence that it existed

practically in the same form as to-day prior to the first Glacial epoch. The genus

is found on the Continent as early as the Lower Miocene formation, while Moles

of an allied type existed at the beginning of the Tertiary epoch.

Habits.— Aristotle seems to have been the first to describe the Mole, but

centuries elapsed before any naturalist turned his attention to study the habits

of this curious animal, a fact accounted for by] the difficulties attending observation.

It was the Frenchman Le Court.who, in the year 1798, made the first

scientific observations on the animal. He imparted his knowledge to Cadet

de Vaux, who published in 1803 his interesting ‘ De la Taupe, de ses moeurs,

de ses habitudes, et des moyens de la détruire,' which is for the most part a

reliable record. In 1829 Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire published his ‘ Cours de l’Histoire

Naturelle des Mammifères,' which, although copying much of Le Court’s original

work, supplied some admirable anatomical observations on the structure of this

animal, which are now very generally accepted. Subsequently Blasius, MacGil-

livray, and Bell have all described the Moles, and Mr. J. E. Harting contributed

a short but able paper on the animal to the ‘Zoologist’ for December 1887.

Notwithstanding that Mr. Lionel Adams pokes fun at the writers who

have from time to time called attention to the Mole’s adaptation to local

environment, the fact remains that the animal is a most extraordinary example

of the way in which Nature endows her children with those characteristics which

will enable them to hold their own, or, in other words, how evolution has altered

and perfected a creature so that it can exist in spite of the bitter struggle for

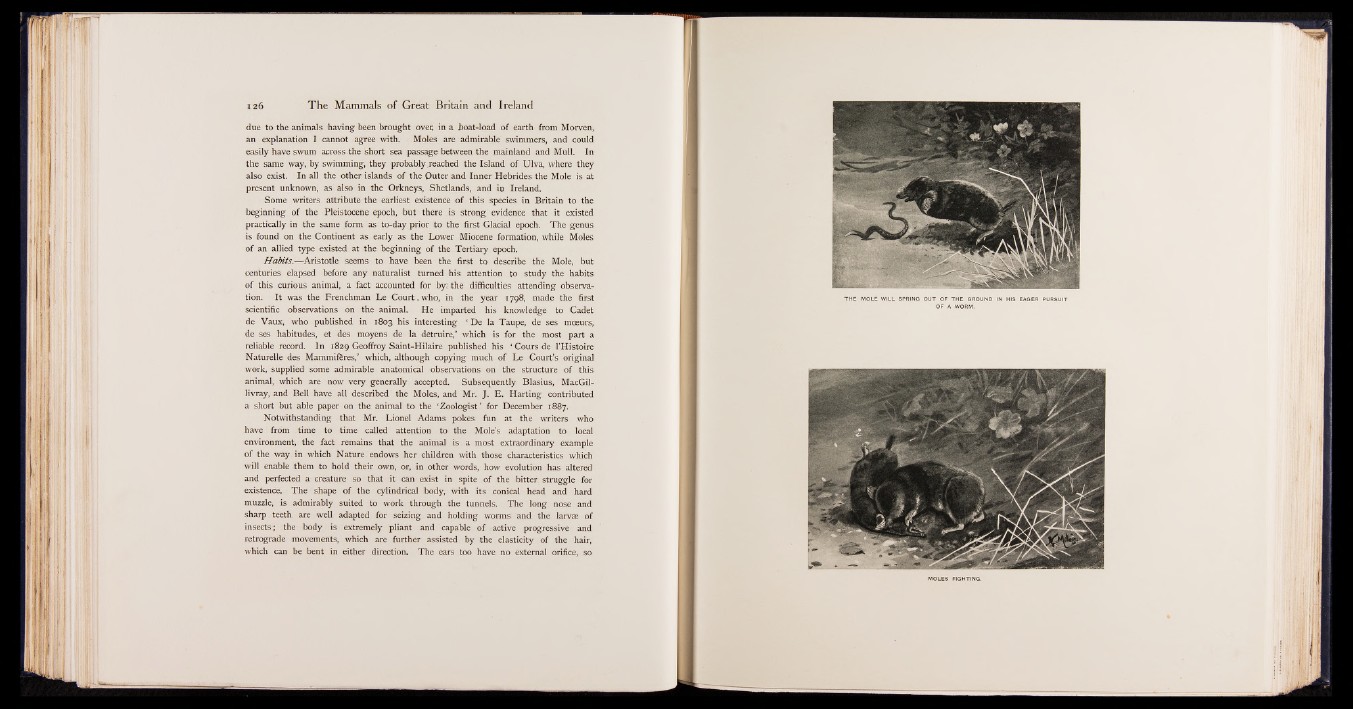

existence. The shape of the cylindrical body, with its conical head and hard

muzzle, is admirably suited to work through the tunnels. The long nose and

sharp teeth are well adapted for seizing and holding worms and the larvae of

insects ; the body is extremely pliant and capable of active progressive and

retrograde movements, which are further assisted by the elasticity of the hair,

which can be bent in either direction. The ears too have no external orifice, so