times in succession.” Mr. J. Henderson, formerly tenant of the shootings of the

Ross of Mull and Tiree, has seen them doing so in calm weather before a storm,

and this is also our experience. Martin, again, in his ancient account, assigns

this habit as. especially exercised in cold weather, whilst other authors consider it as

belonging to the breeding season, and assign it to the males chasing each other,

but the habit is observed quite irrespective of the breeding season. With so many

conflicting ideas, it seems impossible to say with certainty why Seals indulge in

this habit.’ On the following page (p. 22) the same authors give an interesting

description of a fight between two Seals for the possession of a sea trout which

one of them had caught.

The Common Seal is undoubtedly attracted by musical sounds, but that it has

any more discrimination in the matter than other animals I very much doubt.

Almost any strange noise, such as loud talking or singing, appeals to its abundant

sense of curiosity, and it comes to see what is the matter. Some authors would

almost have us believe that it would turn its nose up at the penny whistle if it

once heard the piano-playing of M. Paderewski, and Highlanders have assured me

that Seals have been known to weep at the skilful playing of a pibroch.

Singing certainly brings Seals near, but the unsentimental observation of those

who have long kept these animals in confinement tends to show that it is the

strangeness of any noise that attracts them. Once the Seal has become accustomed

to music or any other unfamiliar sound, and has learnt the cause of it, it takes no

more notice of it than any other creature.

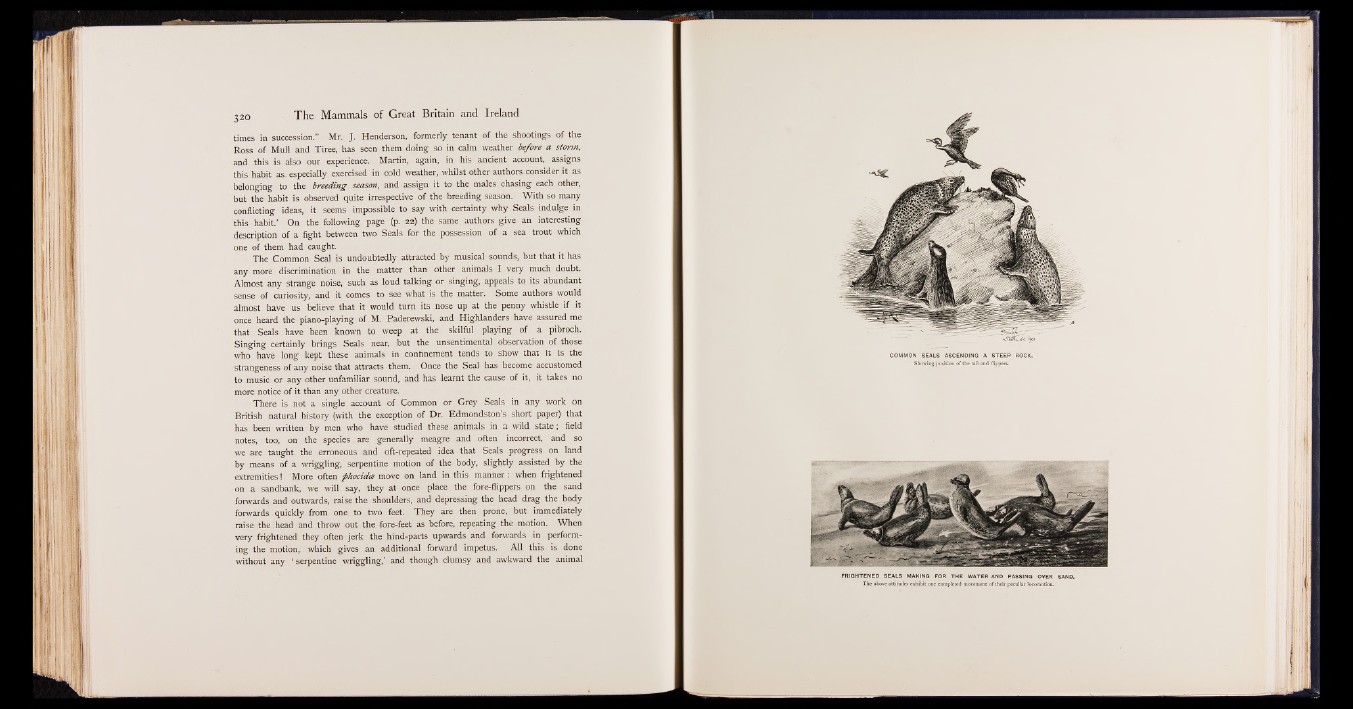

There is not a single account of Common or Grey Seals in any work on

British natural history (with the exception of Dr. Edmondston s short paper) that

has been written by men who have studied these animals in a wild state; field

notes, too, on the species_ are generally meagre and often incorrect, and so

we are taught the erroneous and oft-repeated idea that Seals progress on land

by means of a wriggling, serpentine motion of the body, slightly assisted by the

extremities 1 More often phocidce move on land in this manner: when frightened

on a sandbank, we will say, they at once place the fore-flippers on the sand

forwards and outwards, raise the shoulders, and depressing the head drag the body

forwards quickly from one to two feet. They are then prone, but immediately

raise the head and throw out the fore-feet as before, repeating the motion. When

very frightened, they often jerk the hind-parts upwards and forwards in performing

the motion, which, gives an additional forward impetus. All this is done

without any ‘ serpentine wriggling,’ and though clumsy and awkward the animal