so that a cluster of Bats is a restless, squeaking congregation throughout the

day; no individual can secure much repose. When, as occasionally happens,

a colony is at rest, the voices of the Bats are exceedingly mild and gentle;

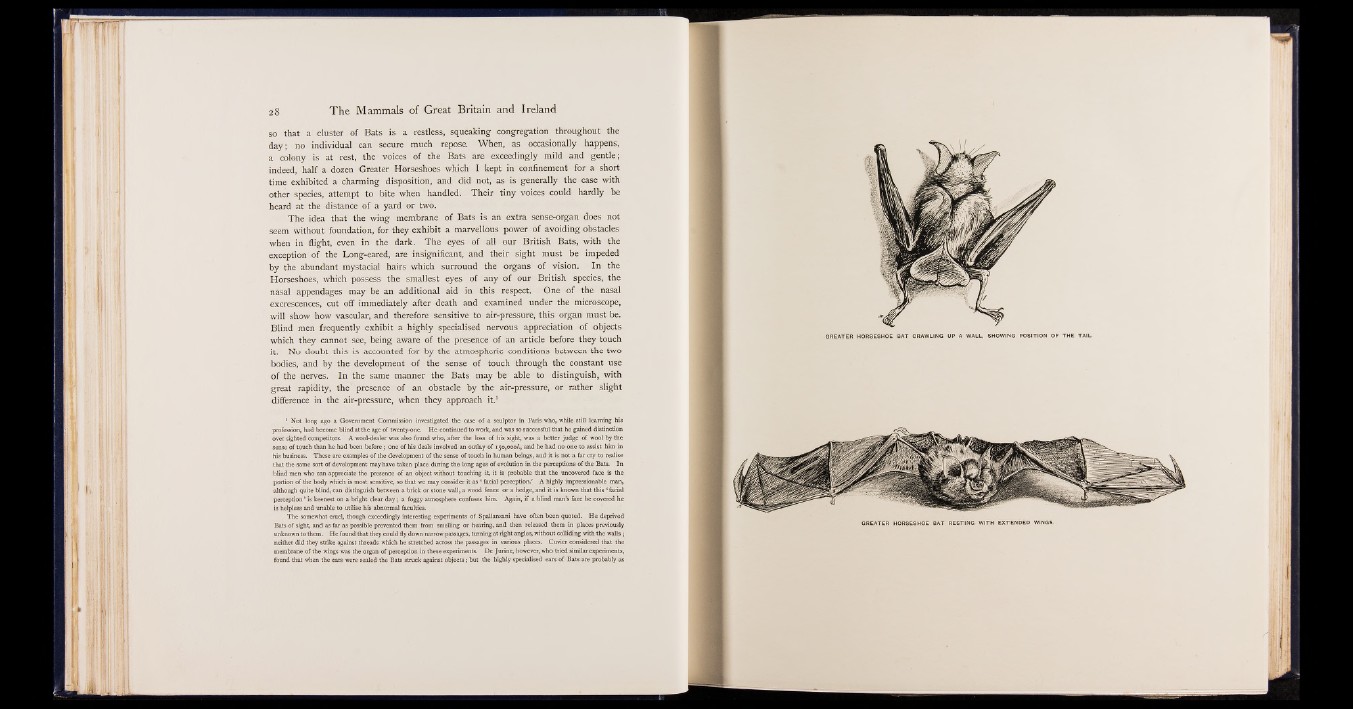

indeed, half a dozen Greater Horseshoes which I kept in confinement for a short

time exhibited a charming disposition, and did not, as is generally the case with

other species, attempt to bite when handled. Their tiny voices could hardly be

heard at the distance of a yard or two.

The idea that the wing membrane of Bats is an extra sense-organ does not

seem without foundation, for they exhibit a marvellous power of avoiding obstacles

when in flight, even in the dark. The eyes of all our British Bats, with the

exception of the Long-eared, are insignificant, and their sight must be impeded

by the abundant mystacial hairs which surround the organs of vision. In the

Horseshoes, which possess the smallest eyes of any of our British species, the

nasal appendages may be an additional aid in this respect. One of the nasal

excrescences, cut off immediately after death and examined under the microscope,

will show how vascular, and therefore sensitive to air-pressure, this organ must be.

Blind men frequently exhibit a highly specialised nervous appreciation of objects

which they cannot see, being aware of the presence of an article before they touch

it. No doubt this is accounted for by the atmospheric conditions between the two

bodies, and by the development of the sense of touch through the constant use

of the nerves. In the same manner the Bats may be able to distinguish, with

great rapidity, the presence, of an obstacle by the air-pressure, or rather slight

difference in the air-pressure, when they approach it.1

1 Not long ago a Government Commission investigated the case of a sculptor in Paris who, while still learning his

profession, had become blind at the age of twenty-one. He continued to work, and was so successful that he gained distinction

over sighted competitors. A wool-dealer was also found who, after the loss of his sight, was a better judge of wool by the

sense of touch than he had been before; one of his deals involved an outlay of 150,000/., and he had no one to assist him in

his business. These are examples o f the development of the sense of touch in human beings, and it is not a far cry to realise

that the same sort o f development may have taken place during the long ages of evolution in the perceptions of the Bats. In

blind men who can appreciate the presence of an object without touching it, it is probable that the uncovered face is the

portion of the body which is most sensitive, so that we may consider it as ‘ facial perception.’ A highly impressionable man,

although quite blind,can distinguish between a brick or stone wall, a wood fence or a hedge, and it is known that this 'facial

perception ’ is keenest on a bright clear d ay; a foggy atmosphere confuses him. Again, if a blind man’s face be covered he

is helpless and unable to utilise his abnormal faculties.

The somewhat cruel, though exceedingly interesting experiments of Spallanzani have often been quoted. He deprived

Bats of sight, and as far as possible prevented them from smelling or hearing, and then released them in places previously

unknown to them. He found that they could fly down narrow passages, turning at right angles, without colliding with the walls;

neither did they strike against threads which he stretched across the passages in various places. Cuvier considered that the

membrane of the wings was the organ of perception in these experiments. De Jurine, however, who tried similar experiments,

found that when the ears were sealed the Bats struck against objects; but the highly specialised ears o f Bats are probably as