their palms extend towards the front, grip the worm firmly. Then the Mole,

having turned the worm, draws it into his mouth with a series of short, quick

jerks, at the same time moving his paws slightly forward.

‘And the effect of this movement is to cause the earth to squirt out at the

tail-end, the tip having been cut off purposely to give the earth free vent.

‘ Thus the Mole secures a clean meal, without any distasteful clay. Evidently

he knows that the tail is the proper part of the worm to bite off, and that he

must begin feeding at the nose to effect his purpose; for it is clear, says

Mr. Runciman, from the conformation of the worm, that only in this way could

the trick be done.’

Besides worms, which are its principal food, the Mole eats lizards, frogs,

larvae, and small mammals, and birds when it can get them. When coming home

one day in 1901, through Warnham Park, I observed the wing of a chaffinch

sticking out of a Mole run, and on pulling it found the entire body had just been

eaten. This might have been done by mice or Moles, while a weasel or stoat

would certainly have eaten the bird above ground; but the whole manner in which

it had been drawn underground pointed to the fact that a Mole was the aggressor.

An interesting account is given1 of a blackbird which was discovered fluttering

above a Mole run; it was held in position by a Mole, which had seized its leg.

Mr. C. A. Hamond’s steward, who discovered the bird, took it in his hand, when

the Mole at once let go its hold. The steward then replaced the bird’s leg in the

run, and after an interval of eight or ten minutes the Mole returned and again

attempted to seize the leg.

On page 33 of his paper on the habits of the Mole Mr. L. Adams gives an

interesting note sent to him by Mr. C. E. Wright, of Kettering, who is a firm believer

in the Mole’s destructiveness in eating partridge and pheasant eggs. Mr. Wright

says his keepers have observed Moles in the act of eating them, and gives an account

of how the Moles work up to the nests and ‘ let them down ’ into their runs, where

the eggs are devoured. These observations are certainly interesting, but it is curious

that such a habit has not been observed elsewhere.

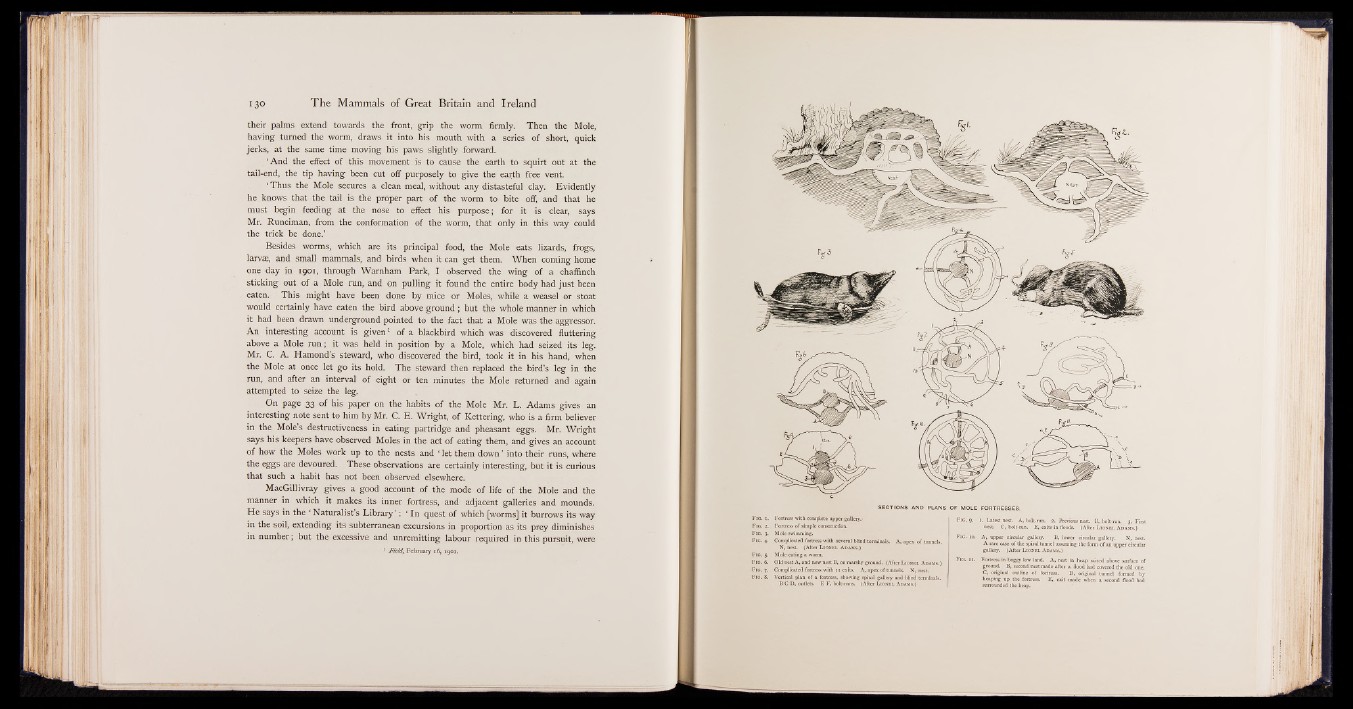

MacGillivray gives a good account of the mode of life of the Mole and the

manner in which it makes its inner fortress, and adjacent galleries and mounds.

He says in the ‘ Naturalist’s Library’ : ‘ In quest of which [worms] it burrows its way

in the soil, extending its subterranean excursions in proportion as its prey diminishes

in number; but the excessive and unremitting labour required in this pursuit, were

1 Field, February 16, 1901.