coast than that at which it dived: another distinct point of difference in the habits

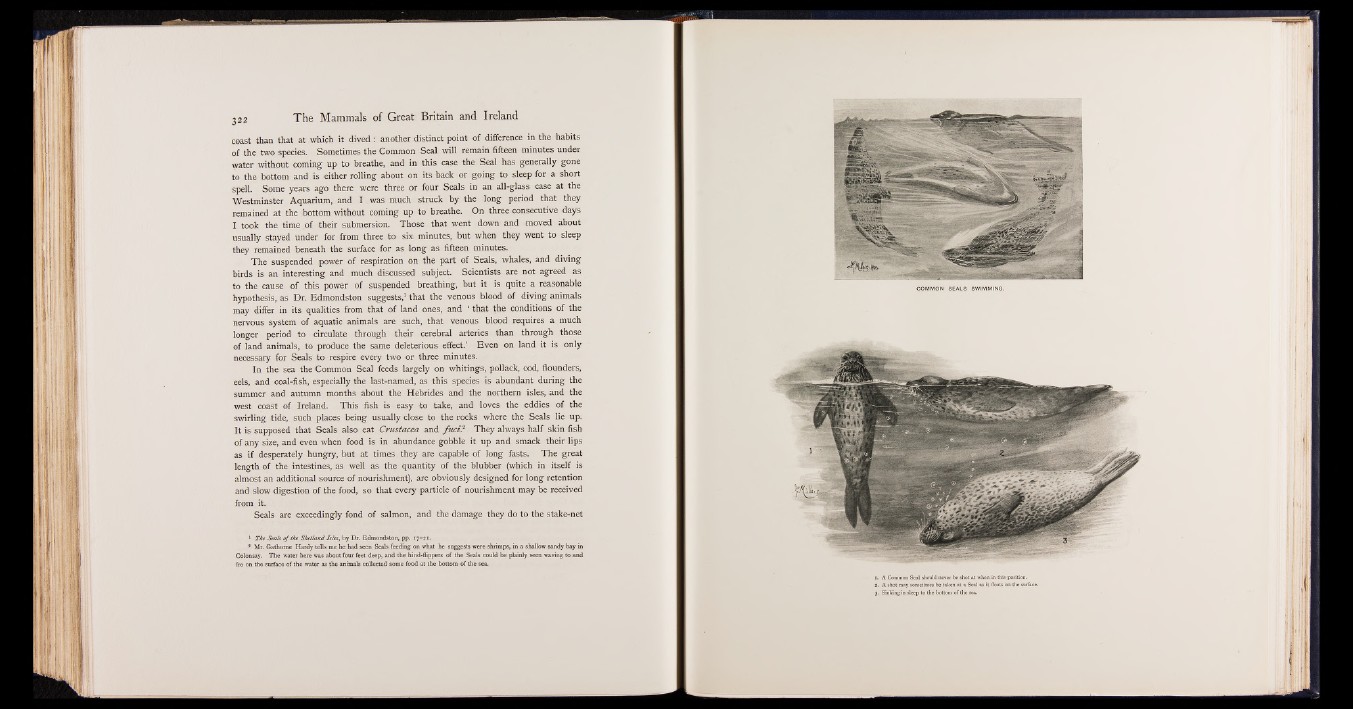

of the two species. Sometimes the Common Seal will remain fifteen minutes under

water without coming up to breathe, and in this case the Seal has generally gone

to the bottom and is either rolling about on its back or going to sleep for a short

spell. Some years ago there were three or four Seals in an all-glass case at the

Westminster Aquarium, and I was much struck by the long period that they

remained at the bottom without coming up to breathe. On three consecutive days

I took the time of their submersion. Those that went down and moved about

usually stayed under for from three to six minutes, but when they went to sleep

they remained beneath the surface for as long as fifteen minutes.

The suspended power of respiration on the part of Seals, whales, and diving

birds is an interesting and much discussed subject. Scientists are not agreed as

to the cause of this power of suspended breathing, but it is quite a reasonable

hypothesis, as Dr. Edmondston suggests,1 that the venous blood of diving animals

may differ in its qualities from that of land ones, and * that the conditions of the

nervous system of aquatic animals are such, that venous blood requires a much

longer period to circulate through their cerebral arteries than through those

of land animals, to produce the same deleterious effect.’ Even on land it is only

necessary for Seals to respire every two or three minutes.

In the sea the Common Seal feeds largely on whitings, pollack, cod, flounders,

eels, and coal-fish, especially the last-named, as this species is abundant during the

summer and autumn months about the Hebrides and the northern isles, and the

west coast of Ireland. This fish is easy to take, and loves the eddies of the

swirling tide, such places being usually close to the rocks where the Seals lie up.

It is supposed that Seals also eat Crustacea and fu ci? They always half skin fish

of any size, and even when food is in abundance gobble it up and smack their lips

as if desperately hungry, but at times they are capable of long fasts. The great

length of the intestines, as well as the quantity of the blubber (which in itself is

almost an additional source of nourishment), are obviously designed for long retention

and slow digestion of the food, so that every particle of nourishment may be received

from it.

Seals are exceedingly fond of salmon, and the damage they do to the stake-net

1 The Seals of the Shetland Isles, by Dr. Edmondston, pp. 17-21.

* Mr. Gathome Hardy tells me he had seen Seals feeding on what he suggests were shrimps, in a shallow sandy bay in

Colonsay. The water here was about four feet deep, and the hind-flippers of the Seals could be plainly seen waving to and

fro on the surface of the water as die animals collected some food at the bottom of the sea.