FELIS UNCIA

TH E SNOW-LEOPARD.

FELIS UNCIA, Erxleb. Syst. Mamm. (1777) p. 508.—Schreb. Säugeth. Th. iii. p. 386, pi. c. (1778).—Gmel. Syst. N a t (1788) vol. i. pt. i.

p. 77. sp. 9 .—Cuv. Ossem. Foss. (1825) vol. iv. p. 427.—H. Smith, in Griff. Anim. King. (1827) vol. iii. p. 468.—Swains. Anim. Menag.

(18 3 8 ) p. 124 Hodg. Journ. Asiat. Soc. Beng. (1842) vol. i i . p. 275.—J. E. Gray, Cat. Mamm. Brit. Mus. (1842) p. 41.—Jard. Nat.

Libr. vol. xvi. p. 191, pi. xiii.—Gerv. Nat. Hist. Mamm. (18 5 5 ) p. 85, pi. xxi. fig. 1 1—Horsf. Proc. Zool. Soc. (1856) p. 395. sp. 17.—

Blyth, Proc. Zool. Soc. (1863) p. 183. sp. 5.—Jerd. Mamm. Ind. (1867) p. 101. sp. 106.—M°Masters, Notes, Jerd. Mamm. Ind. p. 34.

—Hutton, Proc. Zool. Soc. (1869) p. 58.—Dode, Proc. Zool. Soc. (1871) p. 481.—Blanf. Proc. Zool. Soc. (1876) p. 633.—Danf. & Alst.

Proc. Zool. Soc. (1877) p. 272.

ONCE, Penn. Hist. Quad. (1793) vol. i. p. 285. sp. 185.

FELIS PARDUS, Pallas, Zoog. Rosso-Asiat. (1811) t. i. p. 17 ?—Fisch. Zoogr. (1814) p. 220. sp. 3, var. B.

FELIS IRBIS, Ehrenb. Ann. Sc. Nat. (1830) t. xxi. p. 394.—Less. Compl. Buff. (1838) vol. i. p. 406.—Id. Nouv. Tab. Rfcgn. Anim. (1842)

p. 51. sp. 517.—Middend. Sibir. Reise, (1847-59) Band ii. p. 73.—Schrenck, Reis. Forsch. Amurlande, (1858) Band i. p. 96.—Radde,

Reis. Süd. von Ost-Sibir. (1862) Band i. p. 164.—Murray, Geogr. Distr. Mamm. (1866) p. 99.—A. Milne-Edw. Recher. Mamm. p. 213.

LEOPARDUS UNCIA, J. E. Gray, Cat Mamm. Brit. Mus. (1842) p. 41.—Adams, Proc. Zool. Soc. (1856) p. 514.—Hodg. Cat. Coll. Mamm.

Brit. Mus. (18 6 3 ) p. 3. sp. 27.—Id. Cat. Coll. Mamm. & Birds Nep. & Thib. p. 5.

UNCIA IRBIS, J. E. Gray, Ann. & Mag. N a t Hist. vol. xiv..(1854) p. 394.—Id. Cat. Carn. Mamm. (1869) p. 9. fig. 11 (skull).—Id. Proc.

Zool. Sop. (18 6 7 ) p. 262. fig. 1 (skull).

FELIS UNCIOIDES, Horsf. Ann. & Mag. Nat. Hist. (1855). 2nd ser. vol. xvi, p. 105.

FELIS TULLIANA, Valencien. Compt Rend. (1856) t. xlii. p. 1035.—Tchihatcheff, Asie Min. (1856) p. 613, pi. i.

PANTHERA IRBIS, Severtz. Rev. Mag. Zool. (1858) p. 386.—Fitzin. Sitzungsb. Akad. Wiss. Wien, (1868) lviii. p. 478. .

H a b . Snowy regions of Middle Asia, Thibetan plateau. Asia Minor (D a n f o r d ) . Mountains east of Smyrna (B l y t h ).

Altai Mountains (E h r e n b e r g ).: . Amoor river and island of Sakhalien (Sc h r e n c k ). Western China (F o n t a n ie r ).

Turkestan (D o d e ). Corea (S ie b o l d ) .

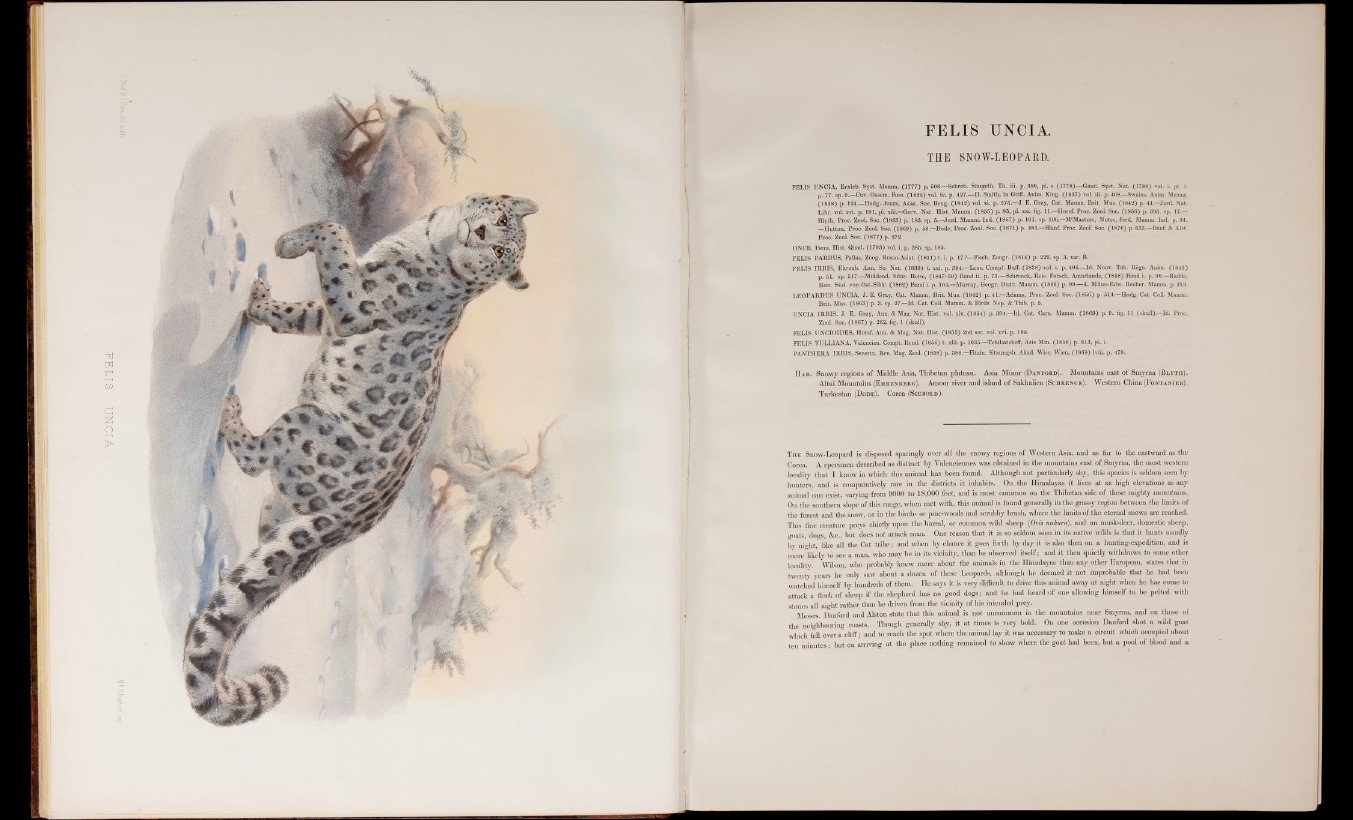

T h e Snow-Leopard is disposed sparingly over all the snowy regions of Western Asia, and as far to the eastward as the

Corea. A specimen described as distinct by Valenciennes was obtained in the mountains east of Smyrna, the most western

locality that I know in which this animal has been found. Although not particularly shy, this species is seldom seen by

hunters, and is comparatively rare in the districts it inhabits. On the Himalayas, it lives at as high elevations as any

animal can exist, varying from 9000 to 18,000 feet, and is most common on the Thibetan side of these mighty mountains.

On the southern slope of this range, when met with, this animal is found generally in the grassy region between the limits of

the forest and the snow, or in the birch- or pine-woods and scrubby brush, where the limits of the eternal snows are reached.

This fine creature preys chiefly upon the burral, or common wild sheep (Ovis nahura), and on musk-deer, domestic sheep,

goats, dogs, &c., but does not attack man. One reason that it is so seldom seen in its native wilds is that it hunts usually

by night, like all the Cat tribe; and when by chance it goes forth by day it is also then on a hunting-expedition, and is

more likely to see a man, who may be in its vicinity, than be observed itself; and it then quietly withdraws to some other

locality. Wilson, who probably knew more about the animals in the Himalayas than any other European, states that in

twenty years he only saw about a dozen of these Leopards, although he deemed it not improbable that he had been

watched himself by hundreds of them. He says it is very difficult to drive this animal away at night when he has come to

attack a flock of sheep if the shepherd has no good dogs; and he had heard of one allowing himself to be pelted with

stones all night rather than be driven from the vicinity of his intended prey.

Messrs. Danford and Alston state that this animal is not uncommon in the mountains near Smyrna, and on those of

the neighbouring coasts. Though generally shy, it at times is very bold. On one occasion Danford shot a wild goat

which fell over a cliff; and to reach the spot where the animal lay it was necessary to make a circuit which occupied about

ten minutes; but on arriving at the place nothing remained to show where the goat had been, but a pool of blood and a