as pertain solely to individuals, or if they do not graduate through a series of examples to the style exhibited by

the types of the species. The skulls, as I have shown (and this fact is patent to every mammalogist), vary even

among examples of the same species to a great degree; and slight differences in crania, therefore, cannot safely

be accepted as indicating distinct forms, any *more than a variation in the colour or shape of the spots, or in

the arrangement of the markings taken by themselves can, properly, be considered sufficient to constitute a species.

Thickness or length of the for is another unreliable character, as is proved by Tigers and Leopards from cold

and warm countries being so differently clothed, and yet belonging to the same species respectively; and therefore

it is to be expected that other species of the Family from different latitudes will vary from each other in a similar

degree. Length of tail is another character only to be accepted with the greatest caution; for it is known that the

caudal vertebrae are not equal in number among individuals of even the same species. Variations in all the points

mentioned above are to be expected among the Cats, and sometimes they occur to an extraordinary degree—witness

the examples of F. pardalis, Linn., called F. melanura; and therefore such forms are to be regarded as varieties,

and not hastily to be announced as newly discovered species. The confusion that existed in the synonymy of many

species was occasioned solely, as I believe, by different authors not being aware of the great amount of variation

that exists among the members of this Family; and, indeed, it is only comparatively lately that this fact has been

understood. The size of spots is an unreliable character; for I have almost always found, among the species of

small-spotted Cats, that there would be individuals having large spots, sometimes inclined to take the form of rings

with light centres; but with the addition of other specimens, these would prove to be only individual variations.

Among the Cats a peculiarity of coloration and markings and of general form is only of specific value when it is

corroborated by the skull also showing conspicuous differences from those of other known species; and when these

characters are sustained by several individuals, then it can be decided with some approach to certainty that a new

species has been discovered. But to accept any one of these characters by itself as sufficient, is more likely to lead

to error than to increase our knowledge of the family. A systematic arrangement of the species of Felidse cannot

be made; but I have endeavoured to group together those that presented a similar style of coloration and a general

mode of life, as well as a resemblance in the formation of their skulls. I commence with F. leo and its representative

in the New World, F. concolor; then F. tigris, which stands alone. Following this are the great Cats

with large-spotted coats, F. uncía, F. onca, and F. pardas ; then the marbled Cats, F. diardi and F. marmorata.

After these I put three species which seem to form a little group of themselves, F. manul, F. pageros, and

F. colocolo. Then come the unspotted species, F. jaguarondi, F. badia, F. eyra, F. planiceps, and F. temminckii. The

striped species are next, viz. F. pardalis and F. tigrina, to be followed by the black-spotted species F. geoffi'oyi,

F. bengalensis, F. vivenina, F. tristis, F. scripta, F. chrysothrix, and F. serval. After these are the red-spotted Cats,

F. euptilura, F. javensis, and F. rubiginosa. F. catus and F. caffra seem to come naturally h e re ; and after them I

place F. ornata as apparently nearest related to F. chaus, which follows it, to be succeeded by F. caudata and

F. shawiana, leading to the lynxes, which are six in number—F. cervaria, F. canadensis, F. pardina, F. lynx, F. rufa,

and F. caracal. F. domestica closes the list of the genus Felis. Concluding the enumeration of the Family I place

Cynailurus jabatas.

GENERA.

The species of Felidae have been separated at various times by different authors into many genera, some of

which included several species, others only one. Some of the distinctive characters of these genera, as given by

their describers, a r e :—a round or vertical pupil, with the orbit completely or incompletely closed behind by bone;

the presence or absence of a first upper premolar; the separation of the nasals from the maxillae by the lengthened

processes of the intermaxillae and frontal bones, as in Catolynx, Gray. This character is seen even more pronounced

in the .skull of lynxes, as well, though not to so great a degree in F. marmorata. One species has been by some

accorded generic rank because the first upper premolar is double-rooted and greatly developed. With the exception

of the Cheetah, or Hunting-Leopard, I have not adopted any of the genera proposed by later writers, but have

retained all the forms in one genus, that of Felis; for it seemed that the characters, some of which have been

enumerated above, were not of sufficient consequence to denote so important a division as that implied by the term

generic. Some of the large Cats, such as the Lion, Ounce, Jaguar, Puma, Leopard, &c., may be considered as

possessing round pupils in almost every condition in which the animal may b e ; yet, as the shape of the pupil in the

majority of the species depends so much upon the quality and quantity of different lights and other causes, this

character becomes one of the most unsatisfactory imaginable upon which to establish generic rank. The form of

the skull also, even in animals closely allied—indeed, it may be said, of individuals belonging to the same species—

varies so greatly that no reliance can be placed upon it for exhibiting generic distinction; and as regards the

teeth, even these may not always be depended on, as TVTivart states (‘The Cat, p. 393) that he examined a skull

of an old lion which showed no trace of upper true molars or even of their alveoli; in fact there was no evidence

of those teeth’s past existence. The Cheetah, however, possesses several prominent and distinctive characters which

may well be considered generic. Its claws are very imperfectly retractile, the skull is very high in proportion

to its length, with short nasals; the first upper premolar is sometimes present, sometimes not, while the second

premolar is very large and projects downwards equally with the sectorial, and the inner cusp of the upper

sectorial is rudimentary. The limbs and tail are also long, the former rather slender.

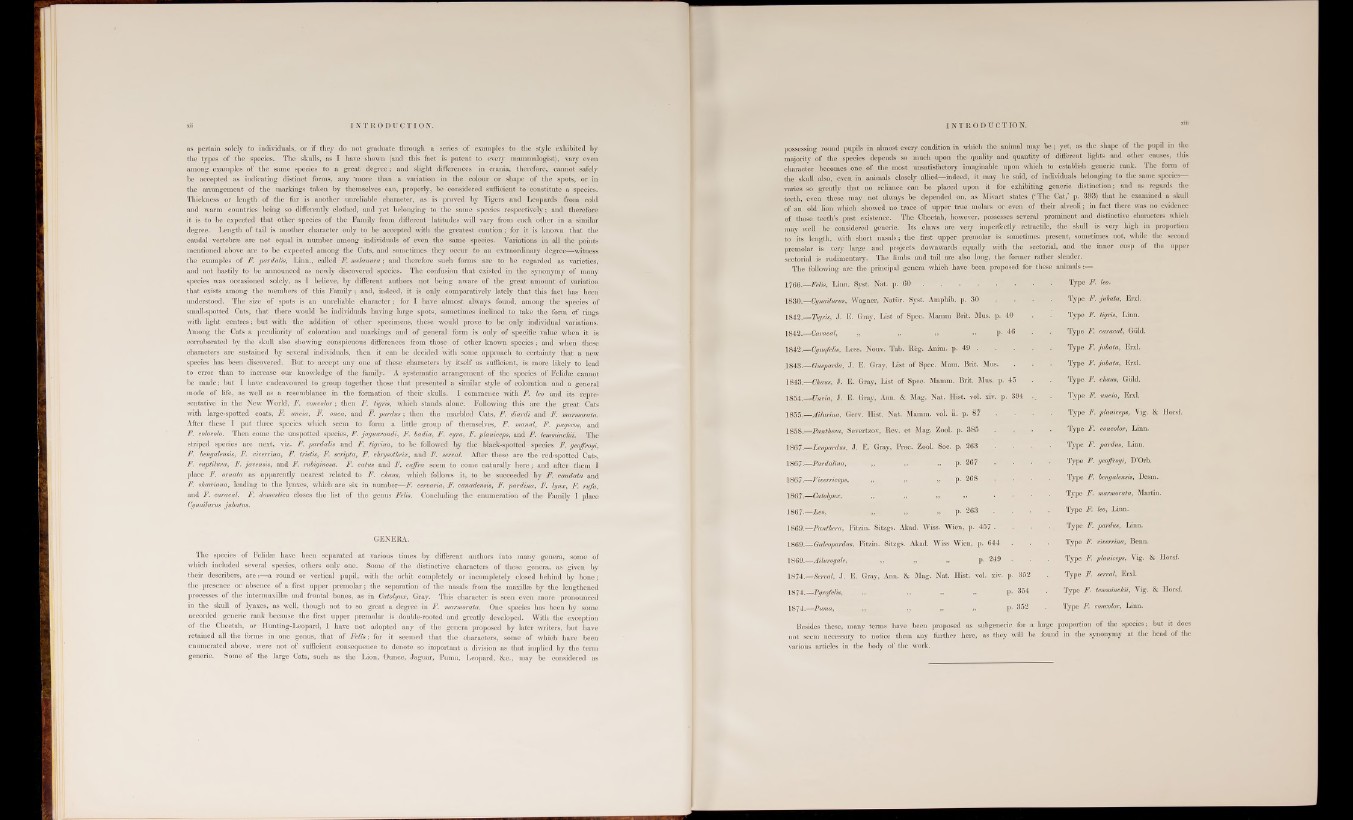

The following are the principal genera which have been proposed for these an imals^ ^^H

1766.—Felis, Linn. Syst. Nat. p. 60 Type F. leo.

1830.—Oynailunts, Wagner, Natiir. Syst. Amphib. p. 30 Type F. jubata, Erxl.

1842.—Tigris, J. E. Gray, List of Spec. Mamm Brit. Mus. p. 40 Type F. tigris, Linn.

1842.—Caracal, „ „ „ P- 46 Type F. caracal, Güld.

1842.—Cynofelis, Less. Nouv. Tab. R&g. Anim. p. 49 . Type F. jubata, Erxl.

1843.—Gueparda, J. E. Gray, List of Spec. Mam. Brit. Mus. Type F. jubata, Erxl.

1843.— Chaus, J. E. Gray, List of Spec. Mamm. Brit. Mus. p. 45 Type F. chaus, Güld.

1854.—Uncia, J. E. Gray, Ann. & Mag. Nat. Hist. vol. xiv. pi. 394 Type F. uncia, Erxl.

1855.—Ailurina, Gerv. Hist. Nat. Mamm. vol. ii. p. 87 Type F. planiceps, Vig. & Horsf.

1858.—Panthera, Severtzov, Rev. et Mag. Zool. p. 385 Type F. concolor, Linn.

18Q7^^^jeopardus, J. E. Gray, Proc. Zool. SoC. p. 263 Type F. par dus, Linn.

1867.-—Pardalina, „ „ „ p- 267 Type F. geoffroyi, D’Orb.

1867.— Fiverriceps, „ „ „ p- 268 Type F. bengalensis, Desm.

1867.—Catolynx, ,, „ » » Type F. marmorata, Martin.

1867.—Leo, „ » » P- 263 Type F. leo, Linn.

1869.—Panthera, Fitzin. Sitzgs. Akad. Wiss. Wien, p. 457 . Type F. pardus, Linn.

1869.—Oaleopardus, Fitzin. Sitzgs. Akad. Wiss Wien, p. 644 Type F. viverrina, Benn.

1869.—Ailurogale, „ ,, ,, p- 249 Type F. planiceps, Vig. & Horsf.

1874.—Semal, J. E. Gray, Ann. & Mag. Nat. Hist. vol. xiv. p. 352 Type F. serval, Erxl.

1874,—Pyrofelis, „ „ „ » p. 354 Type F. temminckii, Vig. & Horsf.

1874.—Puma, ,, ,, „ » p. 352 Type F. concolor, Linn.

Besides these, many terms have been proposed as subgeneric for a large proportion of the species; but it does

not seem necessary to notice them any further here, as they will . be found in the synonymy at the head of the

various articles in the body of the work.