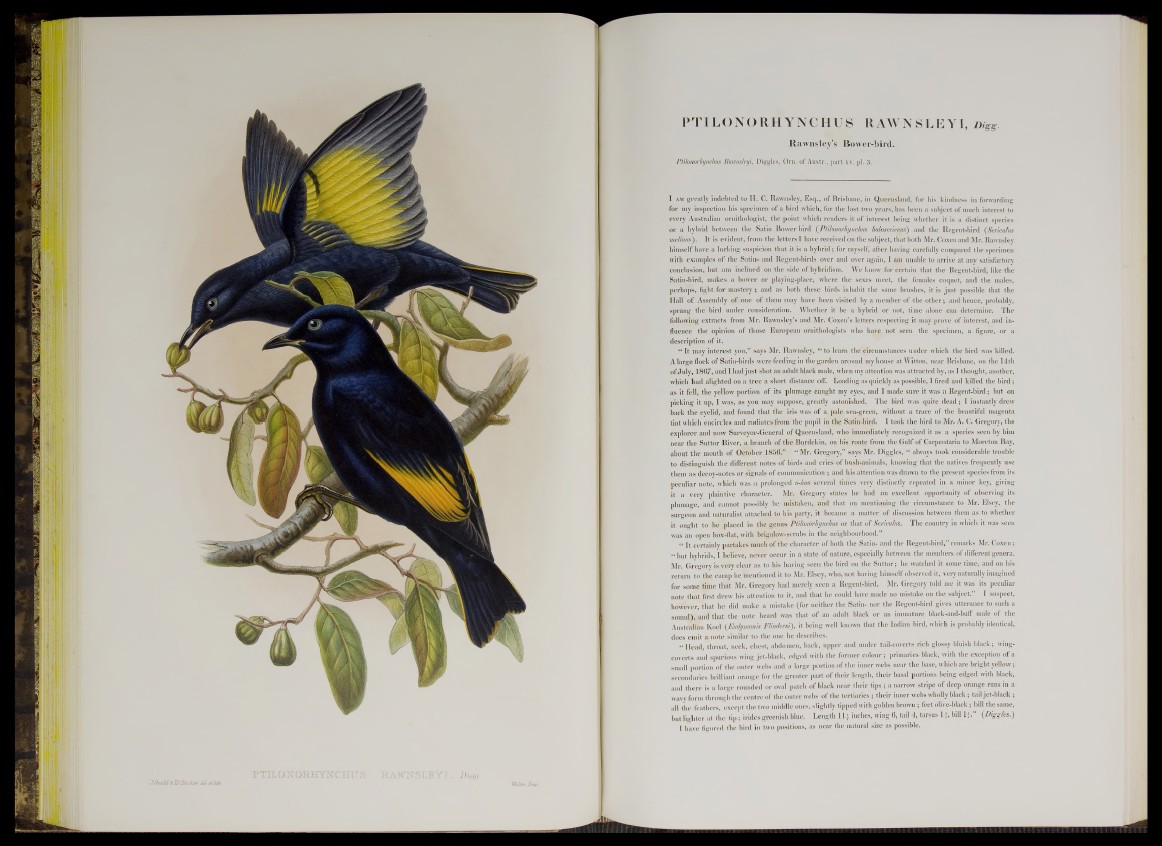

PTILONORHYNCHUS R AWNS LEY I, Digg.

Rawnsley’s Bower-bird.

Ptilonorhynchus Pawnsleyi, Piggies, Orn. of Austr., part xv. pi. 3.

I am greatly indebted to H. C. Rawnsley, Esq., of Brisbane, in Queensland, for his kindness in forwarding

for my inspection his specimen of a bird which, for the last two years, has been a subject of much interest to

every Australian ornithologist, the point which renders it of interest being whether it is a distinct species

or a hybrid between the Satin Bower bird ( Ptilonorhynchus holosericeus) and the Regent-bird (Sericulus

melinus). It is evident, from the letters I have received on the subject, that both Mr. Coxen and Mr. Rawnsley

himself have a lurking suspicion that it is a hybrid ; for myself, after having carefully compared the specimen

with examples of the Satin- and Regent-birds over and over again, I am unable to arrive at any satisfactory

conclusion, but am inclined on the side of hybridism. We know for certain that the Regent-bird, like the

Satin-bird, makes a bovver or playing-place, where the sexes meet, the females coquet, and the males,

perhaps, fight for mastery; and as both these birds inhabit the same brushes, it is just possible that the

Hall of Assembly of one of them may have been visited by a member of the o ther; and hence, probably,

sprang the bird under consideration. Whether it be a hybrid or not, time alone can determine. The

following extracts from Mr. Rawnsley’s and Mr. Coxen’s letters respecting it may prove of interest, and influence

the opinion of those European ornithologists who have not seen the specimen, a figure, or a

description of it.

“ It may interest you,” says Mr. Rawnsley, “ to learn the circumstances under which the bird was killed.

A large flock of Satin-birds were feeding in the garden around my house atWitton, near Brisbane, on the 14th

of July, 1867, and I had just shot an adult black male, when my attention was attracted by, as I thought, another,

which had alighted on a tree a short distance off. Loading as quickly as possible, I fired and killed the bird ;

as it fell, the yellow portion of its plumage caught my eyes, and I made sure it was a Regent-bird; but on

picking it up, I was, as you may suppose, greatly astonished. The bird was quite dead ; I instantly drew

back the eyelid, and found that the iris was of a pale sea-green, without a trace of the beautiful magenta

tint which encircles and radiates from the pupil in the Satin-bird. I took the bird to Mr. A. C. Gregory, the

explorer and now Surveyor-General of Queensland, who immediately recognized it as a species seen by him

near the Suttor River, a branch of the Burdekin, ou his route from the Gulf of Carpentaria to Moreton Bay,

about the month of October 1856.” “ Mr. Gregory,” says Mr. Diggles, “ always took considerable trouble

to distinguish the different notes of birds and cries of bush-animals, knowing that the natives frequently use

them as decoy-notes or signals of communication ; and his attention was drawn to the present species from its

peculiar note, which was a prolonged o-hao several times very distinctly repeated in a minor key, giving

it a very plaintive character. Mr. Gregory states he had an excellent opportunity of observing its

plumage, and cannot possibly be mistaken, and that on mentioning the circumstance to Mr. Elsey, the

surgeon and naturalist attached to his party, it became a matter of discussion between them as to whether

it ouo-ht to be placed in the genus Ptilonorhytichus or that of Sericulus. The country in which it was seen

was an open box-flat, with brigalow-scrubs in the neighbourhood.”

“ It certainly partakes much of the character of both the Satin- and the Regent-bird,” remarks Mr. Coxen ;

1 [)ut hybrids I believe, never occur in a state of nature, especially between the members of different genera.

Mr. Gregory is very clear as to his having seen the bird on the Suttor; he watched it some time, and on his

return to the camp he mentioned it to Mr. Elsey, who, not having himself observed it, very naturally imagined

for some time that Mr. Gregory had merely seen a Regent-bird. Mr. Gregory told me it was its peculiar

note that first drew his attention to it, and that he could have made no mistake on the subject.” I suspect,

however, that he did make a mistake (for neither the Satin- nor the Regent-bird gives utterance to such a

sound), and that the note heard was that of an adult black or an immature black-and-buff male of the

Australian Koel (Eudynamis Winder si), it being well known that the Indian bird, which is probably identical,

does emit a note similar to the one he describes.

“ Head, throat, neck, chest, abdomen, back, upper and under tail-coverts rich glossy bluish black; wing-

coverts and spurious wing jet-black, edged with the former colour; primaries black, with the exception of a

small portion of the outer webs and a large portion of the inner webs near the base, which are bright yellow;

secondaries brilliant orange for the greater part of their length, their basal portions being edged with black,

and there is a large rounded or oval patch of black near their tip s; a narrow stripe of deep orange runs in a

wavy form through the centre of the outer webs of the tertiaries ; their inner webs wholly black ; tail jet-black ;

all the feathers, except the two middle ones, slightly tipped with golden brown ; feet olive-black ; bill the same,

but lighter at the tip ; irides greenish blue. Length 1 I f inches, wing 6, tail 4, tarsus I f , bill I f .” (Diggles.)

I have figured the bird in two positions, as near the natural size as possible.