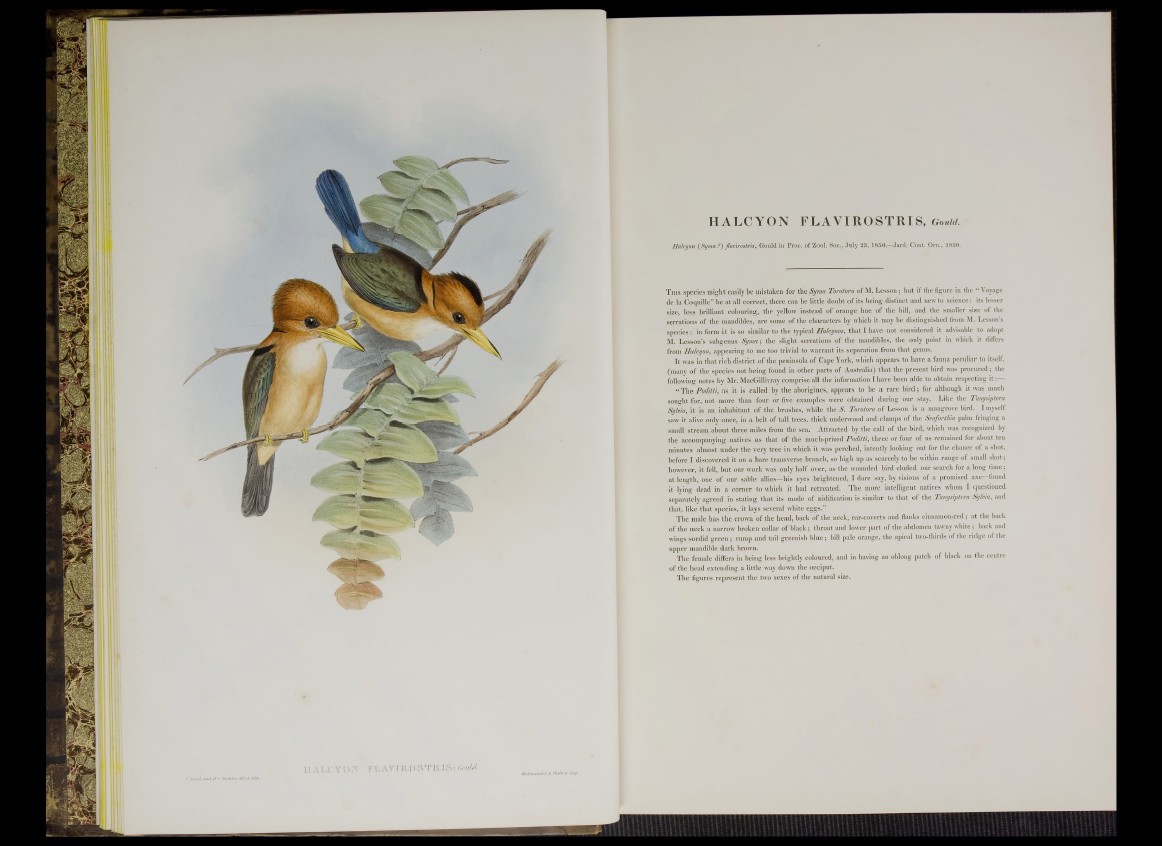

HALCYON FLAVIROSTRIS, Gould.

Halcyon (\Syma f ) jlavirostris, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., July 23, 1850.—Jardj Cont. Orn., 1850.

T h is species might easily be mistaken for the Syma Torotoro of M. Lesson; but if the figure in the “ Voyage

de la Coquille” be at all correct, there can be little doubt of its being distinct and new to science: its lesser

size, less brilliant colouring, the yellow instead of orange hue of the bill, and the smaller size of the

serrations of the mandibles, are some of the characters by which it may be distinguished from M. Lesson’s

species: in form it is so similar to the typical Halcyons, that I have not considered it advisable to adopt

M. Lesson’s subgenus Syma; the slight serrations of the mandibles, the only point in which it differs

from Halcyon, appearing to me too trivial to warrant its separation from that genus.

It was in that rich district of the peninsula of Cape York, which appears to have a fauna peculiar to itself,

(many of the species not being found in other parts of Australia) that the present bird was procured; the

following notes by Mr. MacGillivray comprise all the information I have been able to obtain respecting it

“ The Poditti, as it is called by the aborigines, appears to be a rare b ird; for although it was much

sought for, not more than four or five examples were obtained during our stay. Like the Tanysiptera

Sylvia, it is an inhabitant of the brushes, while the S. Torotoro of Lesson is a mangrove bird. I myself

saw it alive only once, in a belt of tall trees, thick underwood and clumps of the Seafortliia palm fringing a

small stream about three miles from the sea. Attracted by the call of the bird, which was recognized by

the accompanying natives as that of the much-prized Poditti, three or four of us remained for about ten

minutes almost under the very tree in which it was perched, intently looking out for the chance of a shot,

before I discovered it on a bare transverse branch, so high up as scarcely to be within range of small shot;

however, it fell, but our work was only half over, as the wounded bird eluded our search for a long time;

at length, one of our sable allies—his eyes brightened, I dare say, by visions of a promised axe—found

it lying dead in a corner to which it had retreated. The more intelligent natives whom I questioned

separately agreed in stating that its mode of nidification is similar to that of the Tanysiptera Sylvia, and

that, like that species, it lays several white eggs.”

The male has the crown of the head, back of the neck, ear-coverts and flanks cinnamon-red; at the back

of the neck a narrow broken collar of black; throat and lower part of the abdomen tawny w hite; back and

wings sordid green ; rump and tail greenish blue; bill pale orange, the apical two-thirds of the ridge of the

upper mandible dark brown.

The female differs in being less brightly coloured, and in haring an oblong patch of black on the centre

of the head extending a little way down the occiput.

The figures represent the two sexes of the natural size.