Roughly a month later, the treatise had been printed, revealing van Marum’s ardent labour of

the past months. The details of his research have been summarised and discussed elsewhere,

so a short overview should suffice for all purposes here.8

It is particularly interesting to note that his experiments did “not together form any unified

research project”.9 It seems rather that van Marum applied the unprecedented high voltages

the machine could generate to a variety of experimental set-ups that were being

controversially discussed at the time. He indicates as much in the preface to the treatise, when

he recapitulates:

“[T]he history of Electrical Science teaches us that progress in this science has been made in

step with the use of ever larger electrical instruments giving a more powerful electrical force.

Reflecting on this, there seemed to me to be every ground for hoping that a still more

powerful electrical force than used so far, if such could be produced, would lead to new

discoveries.” 10

In other words: “the bigger the better”, and van Marum was hoping to be able to resolve some

controversies about the nature of electricity with Cuthbertson’s generator.

It is equally important to note that van Marum was not performing these experiments on his

own. This would in fact have been impossible for the simple reason that at least two people

were needed to crank up the machine. But van Marum did not only employ mere assistants to

perform menial tasks, he was joined by other eminent scholars in performing experiments in

the Oval Room. More specifically, he was regularly joined by John Cuthbertson, Adriaan

Paets van Troostwijk, Jan Rudolph Deiman and Jan Hendrik van Swinden. For a brief while

John Cuthbertson was even paid the handsome sum of f200,- a month to take care of the

instrument and its accessories, which put him roughly on par with van Marum in terms of

salary. Adriaan Paets van Troostwijk and Jan Rudolph Deiman built a reputation as some of

the finest chemists of the Netherlands. Together with van Marum they used the electrostatic

generator to find out more about the combustion of gases, the oxidation of metals - which was

then referred to as calcination - and the conductivity of various metals and other substances.

Van Swinden and van Marum focused on the former’s longstanding interest in magnetism,

testing the effect the charges generated by the electrostatic generator had on permanent and

artificial magnets. At one point they saw themselves confronted with - and were puzzled by -

electromagnetic effects, but did not pursue these any further, as Oersted famously did some

40 years later.

8 Willem D. Hackmann, “Electrical Researches,” vol. 3, Martinus van Marum: Life & Work (Haarlem: Tjeenk

Willink & Zoon, 1971), 329-378; H.A.M. Snelders, “Martinus van Marum En de Natuurwetenschappen,” in Een

Elektriserend Geleerde: Martinus van Marum 1750-1837, ed. Lodewijk. C. Palm and Anton Wiechmann

(Haarlem: J. Enschede, 1987), 158-168.

Hackmann, “Electrical Researches,” 330-331.

10 Martinus van Marum, “Description o f a Very Large Electrical Machine Installed in Teyler’s Museum at

Haarlem and o f the Experiments Performed with It,” ed. E. Lefebvre, J.G. de Bruijn, and R.J. Forbes, vol. 5,

Martinus van Marum: Life & Work (Leyden: Noordhoff International Publishing, 1974), 4.

1 Gerhard Wiesenfeldt, “Politische Ikonographie von Wissenschaft: Die Abbildung von Teylers ‘ungemein

großer’ Elektrisiermaschine, 1785/87,” NTM 10 (2002): 226.

On occasion the members of Teylers Second Society were involved in the experiments as

well. The minutes of a Society’s meeting in early March 1785 contain a graphic description of

what they witnessed: Van Marum had crisscrossed the Oval Room with a long, thin wire,

through which - in contemporary wording - “electric fire-stuff’ (electric vuur-stof or

phlogiston) was then channelled. The wire immediately started glowing, which in itself must

have looked impressive. Although the description is slightly ambivalent and it is not entirely

clear what the experiment entailed, what clearly transpires is how spectacular it must have

been. The members described how they had the impression that the wire was “surrounded by

long fiery fluff’, and that it “as soon as touched with a finger, emitted sparks of fire.” 1

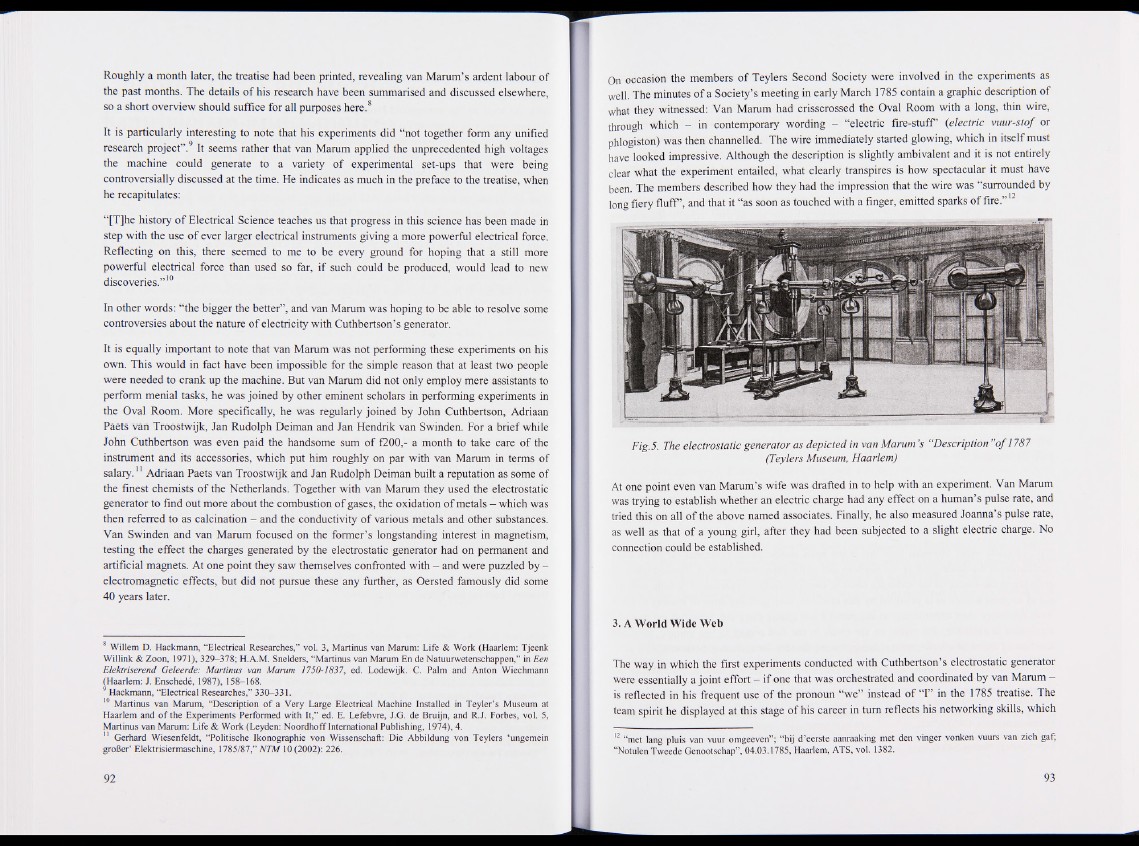

Fig.5. The electrostatic generator as depicted in van Marum’s “Description "of 1787

(Teylers Museum, Haarlem)

At one point even van Marum’s wife was drafted in to help with an experiment. Van Marum

was trying to establish whether an electric charge had any effect on a human’s pulse rate, and

tried this on all of the above named associates. Finally, he also measured Joanna’s pulse rate,

as well as that of a young girl, after they had been subjected to a slight electric charge. No

connection could be established.

3. A World Wide Web

The way in which the first experiments conducted with Cuthbertson’s electrostatic generator

were essentially a joint effort — if one that was orchestrated and coordinated by van Marum —

is reflected in his frequent use of the pronoun “we” instead of “I” in the 1785 treatise. The

team spirit he displayed at this stage of his career in turn reflects his networking skills, which

12 “met lang pluis van vuur omgeeven”; “bij d’cerstc aanraaking met den vinger vonken vuurs van zich gaf,

“Notulen Tweede Genootschap”, 04.03.1785, Haarlem, ATS, vol. 1382.