visitors could shore up their credentials as fully fledged members of the bourgeoisie through

the aesthetic contemplation of works of art in public. Put differently, exhibitions - and by

extension, as they were increasingly defined by the public display of their collections,

museums too - were turning into places to “see and be seen”.

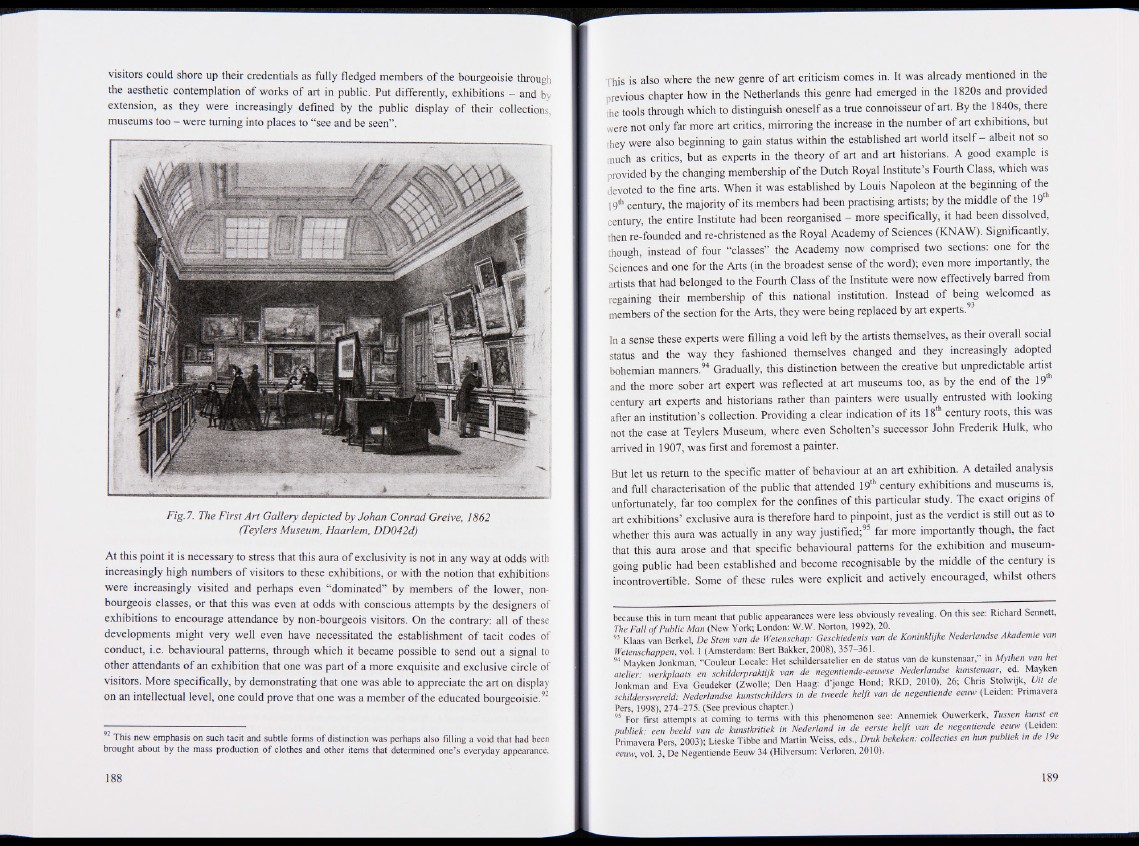

Fig.7. The First Art Gallery depicted by Johan Conrad Greive, 1862

(Teylers Museum, Haarlem, DD042d)

At this point it is necessary to stress that this aura of exclusivity is not in any way at odds with

increasingly high numbers of visitors to these exhibitions, or with the notion that exhibitions

were increasingly visited and perhaps even “dominated” by members of the lower, nonbourgeois

classes, or that this was even at odds with conscious attempts by the designers of

exhibitions to encourage attendance by non-bourgeois visitors. On the contrary: all of these

developments might very well even have necessitated the establishment of tacit codes of

conduct, i.e. behavioural patterns, through which it became possible to send out a signal to

other attendants of an exhibition that one was part of a more exquisite and exclusive circle of

visitors. More specifically, by demonstrating that one was able to appreciate the art on display

on an intellectual level, one could prove that one was a member of the educated bourgeoisie.92

This new emphasis on such tacit and subtle forms o f distinction was perhaps also filling a void that had been

brought about by the mass production o f clothes and other items that determined one’s everyday appearance,

This is also where the new genre of art criticism comes in. It was already mentioned in the

previous chapter how in the Netherlands this genre had emerged in the 1820s and provided

the tools through which to distinguish oneself as a true connoisseur of art. By the 1840s, there

were not only far more art critics, mirroring the increase in the number of art exhibitions, but

they were also beginning to gain status within the established art world itself gfalbeit not so

much as critics, but as experts in the theory of art and art historians. A good example is

provided by the changing membership of the Dutch Royal Institute’s Fourth Class, which was

devoted to the fine arts. When it was established by Louis Napoleon at the beginning of the

19th century, the majority of its members had been practising artists; by the middle of the 19

century, the entire Institute had been reorganised# more specifically, it had been dissolved,

then re-founded and re-christened as the Royal Academy of Sciences (KNAW). Significantly,

though, instead of four “classes” the Academy now comprised two sections: one for the

Sciences and one for the Arts (in the broadest sense of the word); even more importantly, the

artists that had belonged to the Fourth Class of the Institute were now effectively barred from

regaining their membership of this national institution. Instead of being welcomed as

members of the section for the Arts, they were being replaced by art experts.

In a sense these experts were filling a void left by the artists themselves, as their overall social

status and the way they fashioned themselves changed and they increasingly adopted

bohemian manners.94 Gradually, this distinction between the creative but unpredictable artist

and the more sober art expert was reflected at art museums too, as by the end of the 19

century art experts and historians rather than painters were usually entrusted with looking

after an institution’s collection. Providing a clear indication of its 18th century roots, this was

not the case at Teylers Museum, where even Scholten’s successor John Frederik Hulk, who

arrived in 1907, was first and foremost a painter.

But let us return to the specific matter of behaviour at an art exhibition. A detailed analysis

and full characterisation of the public that attended 19th century exhibitions and museums is,

unfortunately, far too complex for the confines of this particular study. The exact origins of

art exhibitions’ exclusive aura is therefore hard to pinpoint, just as the verdict is still out as to

whether this aura was actually in any way justified;95 far more importantly though, the fact

that this aura arose and that specific behavioural patterns for the exhibition and museum-

going public had been established and become recognisable by the middle of the century is

incontrovertible. Some of these rules were explicit and actively encouraged, whilst others

because this in turn meant that public appearances were less obviously revealing. On this see: Richard Sennett,

The Fall o f Public Man (New York; London: W.W. Norton, 1992), 20.

93 Klaas van Berkel, De Stem van de Wetenschap: Geschiedenis van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van

Wetenschappen, vol. 1 (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2008), 35|l i 361.

94 Mayken Jonkman, “Couleur Locale: Het schildersatelier en de status van de kunstenaar,” in Mythen van het

atelier: werkplaats en schilderpraktijk van de negentiende-eeuwse Nederlandse kunstenaar, ed. Mayken

Jonkman and Eva Geudeker (Zwolle; Den Haag: d’jonge Hond; RKD, 2010), 26; Chris Stolwijk, Ult de

schilderswereld: Nederlandse kunstschilders in de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw (Leiden: Pnmavera

Pers, 1998), 274-275. (See previous chapter.) , , „

95 For first attempts at coming to terms with this phenomenon see: Annemiek Ouwerkerk, Tussen kunst en

publiek■ een beeid van de kunstkritiek in Nederland in de eerste helft van de negentiende eeuw (Leiden:

Primavera Pers, 2003); Lieske Tibbe and Martin Weiss, eds., Druk bekeken: collecties en hun publiek in de 19e

eeuw, vol. 3, De Negentiende Eeuw 34 (Hilversum: Verloren, 2010).