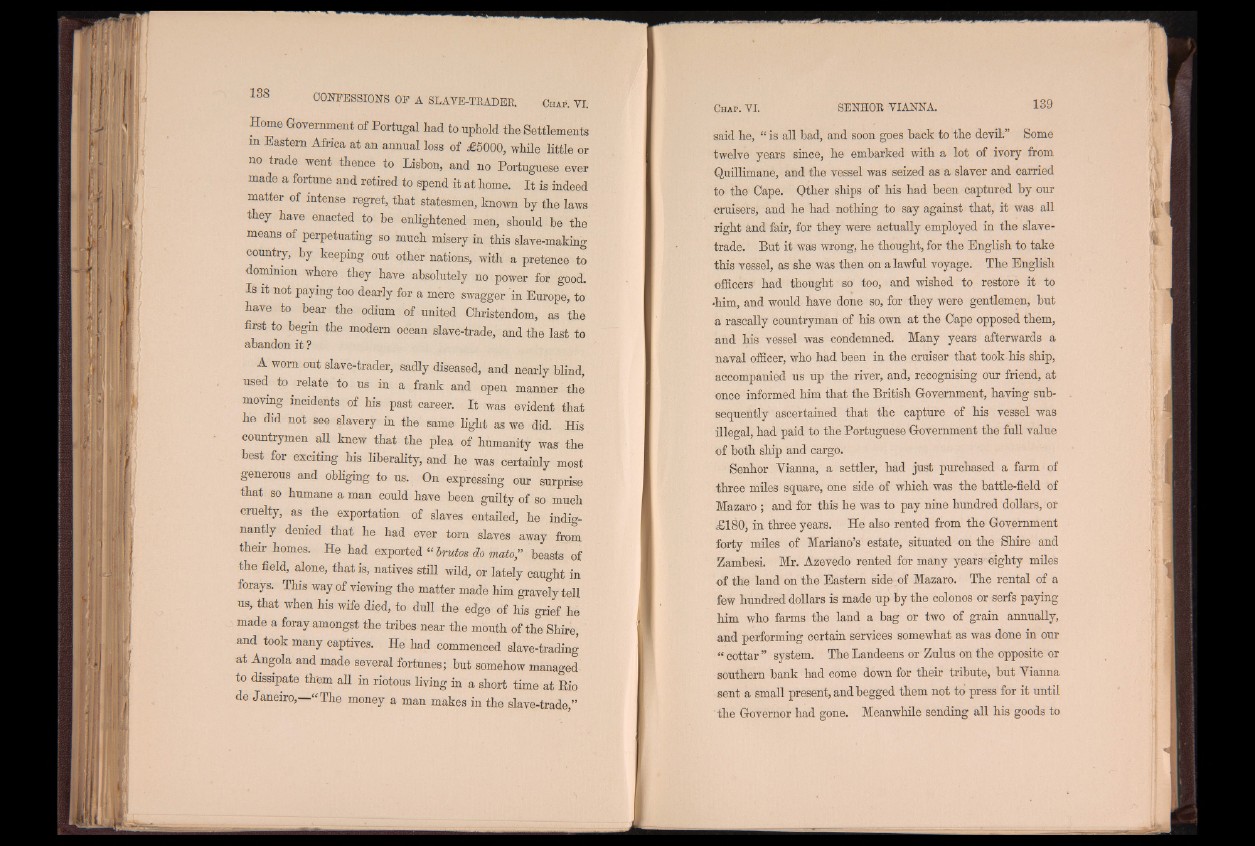

Home Government of Portugal had to uphold the Settlements

m Eastern Africa at an annual loss of £5000, while little or

no trade went thence to Lisbon, and no Portuguese ever

made a fortune and retired to spend it at home. I t is indeed

matter of intense regret, that statesmen, known by the laws

they have enacted to be enlightened men, should be the

means of perpetuating so much misery in this slave-making

country, by keeping out other nations, with a pretence to

dominion where they have absolutely no power for good.

Is it not paying too dearly for a mere swagger in Europe, to

have to bear the odium of united Christendom, as the

first to begin the modem ocean slave-trade, and the last to

abandon it ?

A worn out slave-trader, sadly diseased, and nearly blind,

used to relate to us in a frank and open manner the

moving incidents of his past career. I t was evident that

he did not see slavery in the same light as we did. His

countrymen all knew that the plea of humanity was the

best for exciting his liberality, and he was certainly most

generous and obliging to us. On expressing our surprise

that so humane a man could have been guilty of so much

cruelty, as the exportation of slaves entailed, he indignantly

denied that he had ever tom slaves away from

their homes. He had exported “ brutos do mato” beasts of

the field, alone, that is, natives still wild, or lately caught in

forays. This way of viewing the matter made him gravely tell

us, that when his wife died, to dull the edge of his grief he

made a foray amongst the tribes near the mouth of the Shire,

and took many captives. He had commenced slave-trading

a t Angola and made several fortunes; but somehow managed

to dissipate them all in riotous living in a short time at Eio

de Janeiro,—“ The money a man makes in the slave-trade,”

said he, “ is all bad, and soon goes back to the devil.” Some

twelve years since, he embarked with a lot of ivory from

Quillimane, and the vessel was seized as a slaver and carried

to the Cape. Other ships of his had been captured by our

cruisers, and he had nothing to say against that, it was all

right and fair, for they were actually employed in the slave-

trade. But it was wrong, he thought, for the English to take

this vessel, as she was then on a lawful voyage. The English

officers had thought so too, and wished to restore it to

•him, and would have done so, for they were gentlemen, but

a rascally countryman of his own at the Cape opposed them,

and his vessel was condemned. Many years afterwards a

naval officer, who had been in the cruiser that took his ship,

accompanied us up the river, and, recognising our friend, at

once informed him that the British Government, having subsequently

ascertained that the capture of his vessel was

illegal, had paid to the Portuguese Government the full value

of both ship and cargo.

Senhor Yianna, a settler, had just purchased a farm of

three m ile s square, one side of which was the battle-field of

Mazaro ; and for this he was to pay nine hundred dollars, or

£180, in three years. He also rented from the Government

forty m iles of Mariano’s estate, situated on the Shire and

Zambesi. Mr. Azevedo rented for many years eighty miles

of the land on the Eastern side of Mazaro. The rental of a

few hundred dollars is made up by the colonos or serfs paying

him who farms the land a bag or two of grain annually,

and performing certain services somewhat as was done in our

“ cottar ” system. The Landeens or Zulus on the opposite or

southern bank had come down for their tribute, but Yianna

sent a small present, and begged them not to press for it until

the Governor had gone. Meanwhile sending all his goods to