streams flowing into it. I t is quite remarkable for the abundance

of fish; and we saw upwards of fifty large canoes

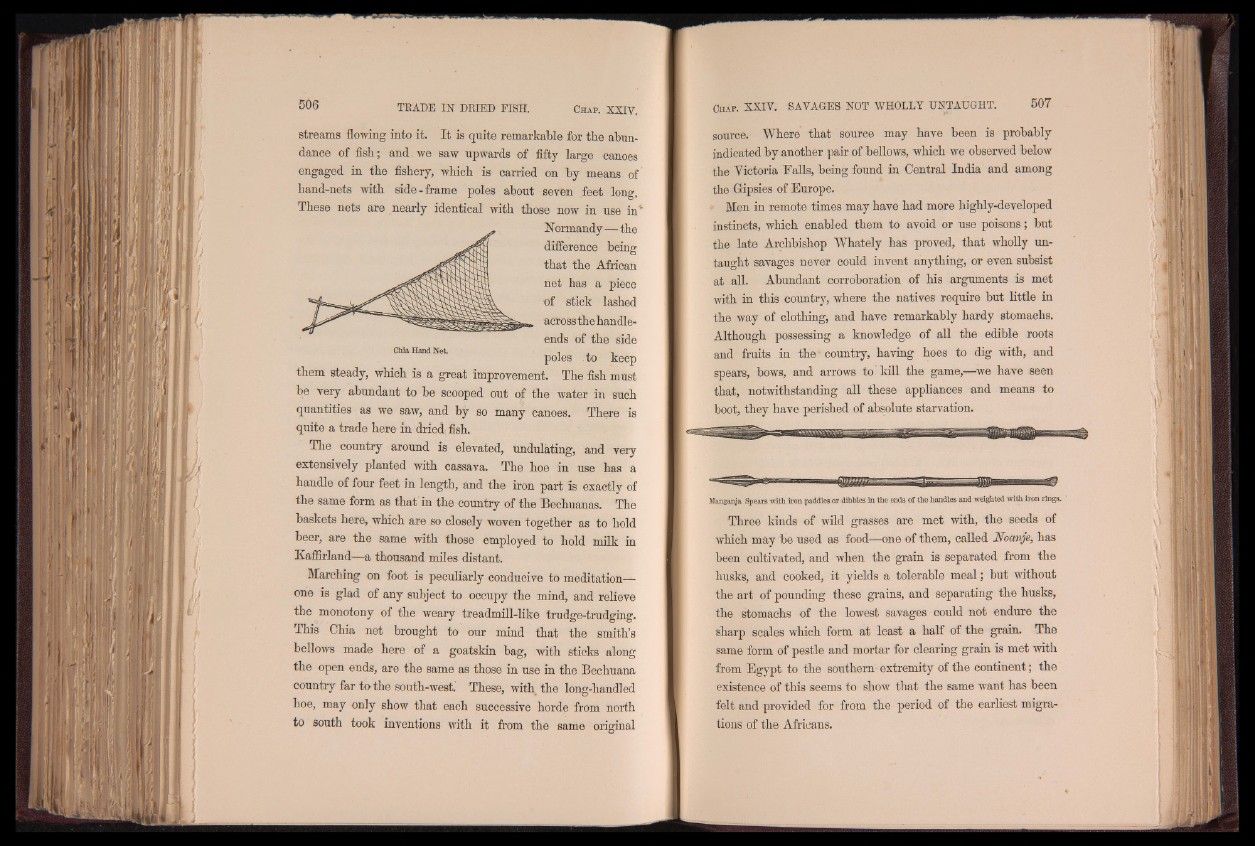

engaged in the fishery, which is carried on by means of

hand-nets with side-frame poles about seven feet long.

These nets are nearly identical with those now in use in1

Normandy — the

difference being

that the African

net has a piece

of stick lashed

across the handle-

ends of the side

Chla Hand Net. i . , poles to keep

them steady, which is a great improvement. The fish must

be very abundant to be scooped Out of the water in such

quantities as we saw, and by so many canoes. There is

quite a trade here in dried fish.

The country around is elevated, undulating, and very

extensively planted with cassava. The hoe in use has a

handle of four feet in length, and the iron part is exactly of

the same form as that in the country of the Bechuanas. The

baskets here, which are so closely woven together as to hold

beer, are the same with those employed to hold milk in

KafiSrland—a thousand miles distant.

Marching on foot is peculiarly conducive to meditation-

one is glad of any subject to occupy the mind, and relieve

the monotony of the weary treadmill-like trudge-trudging.

This Chia net brought to our mind that the smith’s

bellows made here of a goatskin bag, with sticks along

the open ends, are the same as those in use in the Bechuana

country far to the south-west. These, with the long-handled

hoe, may only show that each successive horde from north

to south took inventions with it from the same original

source. Where that source may have been is probably

indicated by another pair of bellows, which we observed below

the Victoria Palls, being found in Central India and among

the Gipsies of Europe.

Men in remote times may have had more highly-developed

instincts, which enabled them to avoid or use poisons; but

the late Archbishop Whately has proved, that wholly untaught

savages never could invent anything, or even subsist

at all. Abundant corroboration of his arguments is met

with in this country, where the natives require but little in

the way of clothing, and have remarkably hardy stomachs.

Although possessing a knowledge of all the edible roots

and fruits in th e1 country, having hoes to dig with, and

spears, bows, and arrows to kill the game,—we have seen

that, notwithstanding all these appliances and means to

boot, they have perished of absolute starvation.

Manganja Spears with iron paddles or dibbles in the ends of the handles and weighted with iron rings.

Three kinds of wild grasses are met with, the seeds of

which may be used as food—one of them, called Noanje, has

been cultivated, and when the grain is separated from the

husks, and cooked, it yields a tolerable meal; but without

the art of pounding these grains, and separating the husks,

the stomachs of the lowest savages could not endure the

sharp scales which form at least a half of the grain. The

same form of pestle and mortar for clearing grain is met with

from Egypt to the southern extremity of the continent; the

existence of this seems to show that the same want has been

felt and provided for from the period of the earliest migrations

of the Africans.