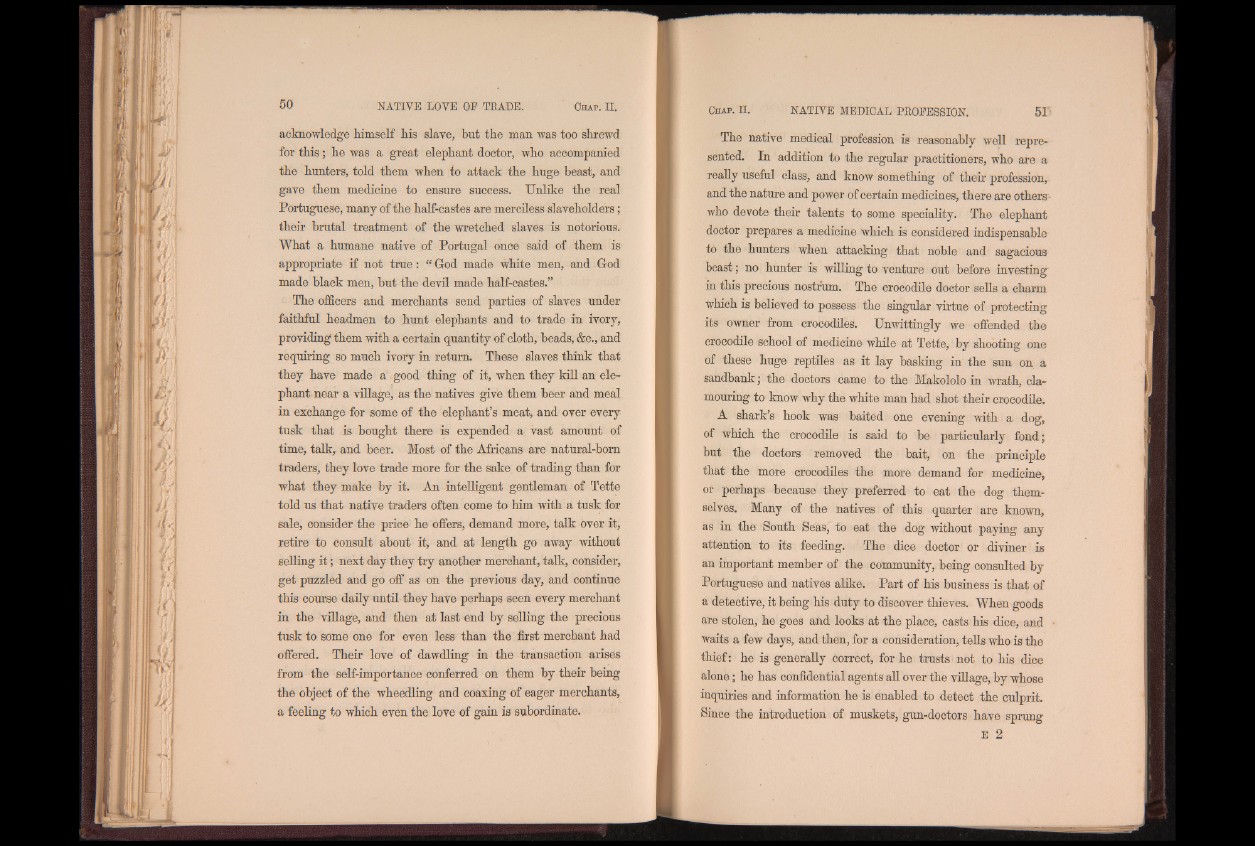

acknowledge himself his slave, but the man was too shrewd

for th is; he was a great elephant doctor, who accompanied

the hunters, told them when to attack the huge beast, and

gave them medicine to ensure success. TJnlike the real

Portuguese, many of the half-castes are merciless slaveholders;

their brutal treatment of the wretched slaves is notorious.

What a humane native of Portugal once said of them is

appropriate if not tru e : “ God made white men, and God

made black men, hut the devil made half-castes.”

The officers and merchants send parties of slaves under

faithful headmen to hunt elephants and to trade in ivory,

providing them with a certain quantity of cloth, heads, &c., and

requiring so much ivory in return. These slaves think that

they have made a good thing of it, when they kill an elephant

near a village, as the natives give them beer and meal

in exchange for some of the elephant’s meat, and over every

tusk that is bought there is expended a vast amount of

time, talk, and beer. Most of the Africans are natural-born

traders, they love trade more for the sake of trading than for

what they make by it. An intelligent gentleman of Tette

told us that native traders often come to him with a tusk for

sale, consider the price he offers, demand more, talk over it,

retire to consult about it, and at length go away without

selling i t ; next day they try another merchant, talk, consider,

get puzzled and go off as on the previous day, and continue

this course daily until they have perhaps seen every merchant

in the village, and then at last end by selling the precious

tusk to some one for even less than the first merchant had

offered. Their love of dawdling in the transaction arises

from the self-importance conferred on them by their being

the object of the wheedling and coaxing of eager merchants,

a feeling to which even the love of gain is subordinate.

The native medical profession is reasonably well represented.

In addition to the regular practitioners, who are a

really useful class, and know something of their profession,

and the nature and power of certain medicines, there are others -

who devote their talents to some speciality. The elephant

doctor prepares a medicine which is considered indispensable

to the hunters when attacking that noble and sagacious

beast; no hunter is willing to venture out before investing

in this precious nostrum. The crocodile doctor sells a charm

which is believed to possess the singular virtue of protecting

its owner from crocodiles. Unwittingly we offended the

crocodile school of medicine while at Tette, by shooting one

of these huge reptiles as it lay basking in the sun on a

sandbank; the doctors came to the Makololo in wrath, clamouring

to know why the white man had shot their crocodile.

A shark’s hook was baited one evening with a dog,

of which the crocodile is said to be particularly fond;

but the doctors removed the bait, on the principle

that the more crocodiles the more demand for medicine,

or perhaps because they preferred to eat the dog themselves.

Many of the natives of this quarter are known,

as in the South Seas, to eat the dog without paying any

attention to its feeding. The dice doctor or diviner is

an important member of the community, being consulted by

Portuguese and natives alike. Part of his business is that of

a detective, it being his duty to discover thieves. When goods

are stolen, he goes and looks at the place, casts his dice, and

waits a few days, and then, for a consideration, tells who is the

thief: he is generally correct, for he trusts not to his dice

alone; he has confidential agents all over the village, by whose

inquiries and information he is enabled to detect the culprit.

Since the introduction of muskets, gun-doctors have sprung

E 2