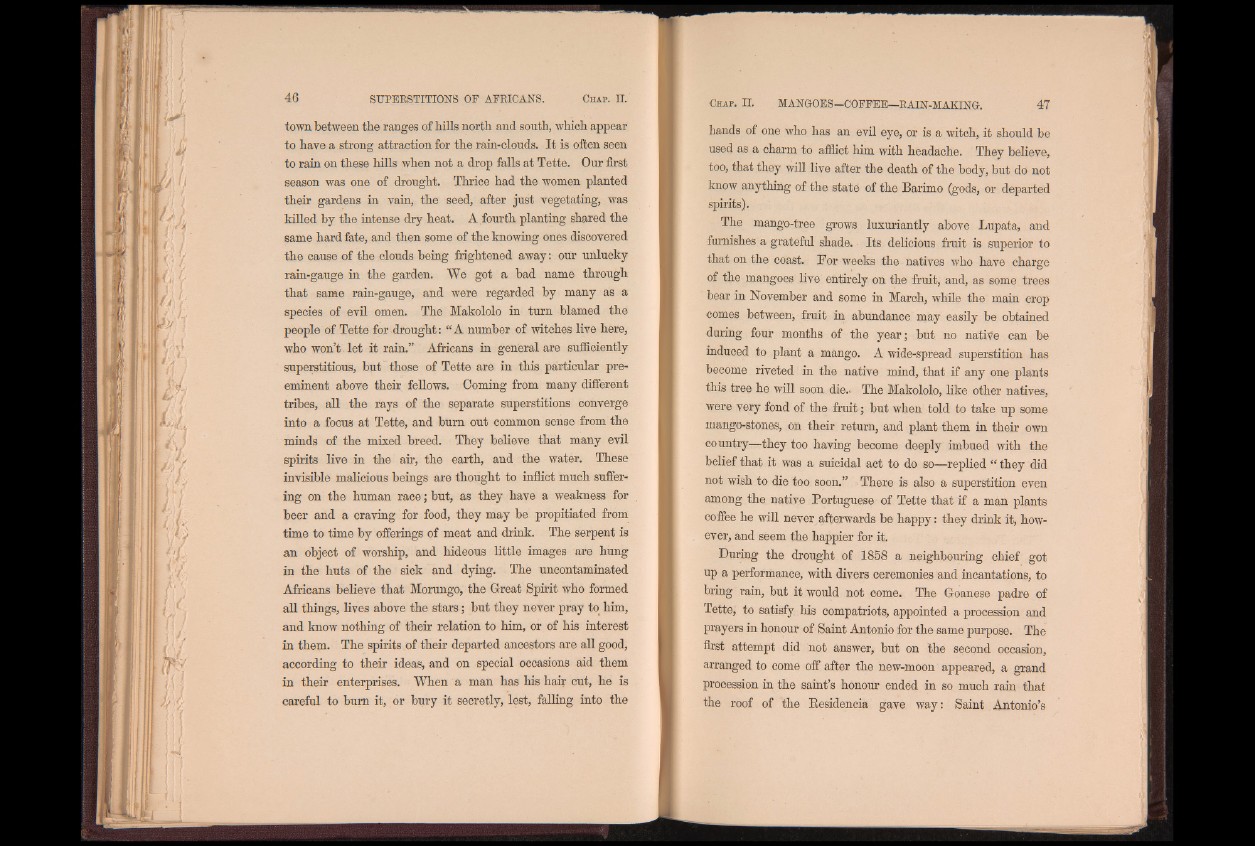

town between tbe ranges of hills north and south, which appear

to have a strong attraction for the rain-clouds. I t is often seen

to rain on these hills when not a drop falls at Tette. Our first

season was one of drought. Thrice had the women planted

their gardens in vain, the seed, after just vegetating, was

killed by the intense dry heat. A,fourth planting shared the

same hard fate, and then some of the knowing ones discovered

the cause of the clouds being frightened away: our unlucky

rain-gauge in the garden. We got a bad name through

that same rain-gauge, and were regarded by many as a

species of evil omen. The Makololo in turn blamed the

people of Tette for drought: “A number of witches live here,

who won’t let it rain.” Africans in general are sufficiently

superstitious, but those of Tette are in this particular preeminent

above their fellows. Coming from many different

tribes, all the rays of the separate superstitions converge

into a focus at Tette, and bum out common sense from the

minds of the mixed breed. They believe that many evil

spirits live in the air, the earth, and the water. These

invisible malicious beings are thought to inflict much suffering

on the human race; but, as they have a weakness for

beer and a craving for food, they may be propitiated from

time to time by offerings of meat and drink. The serpent is

an object of worship, and hideous little images are hung

in the huts of the sick and dying. The uncontaminated

Africans believe that Morungo, the Great Spirit who formed

all things, lives above the stars; but they never pray to him,

and know nothing of their relation to him, or of his interest

in them. The spirits of their departed ancestors are all good,

according to their ideas, and on special occasions aid them

in their enterprises. When a man has his hair cut, he is

careful to bum it, or bury it secretly, lest, falling into the

hands of one who has an evil eye, or is a witch, it should be

used as a charm to afflict him with headache. They believe,

too, that they will live after the death of the body, but do not

know anything of the state of the Barimo (gods, or departed

spirits).

The mango-tree grows luxuriantly above Lupata, and

furnishes a grateful shade. Its delicious fruit is superior to

that on the coast. For weeks the natives who have charge

of the mangoes live entirely on the fruit, and, as some trees

bear in November and some in March, while the main crop

comes between, fruit in abundance may easily be obtained

during four months of the year; but no natife can be

induced to plant a mango. A wide-spread superstition has

become riveted in the native mind, that if any one plants

this tree he will soon die.. The Makololo, like other natives,

were very fond of the fruit; but when told to take up some

mango-stones, on their return, and plant them in their own

country—they too having become deeply imbued with the

belief that it was a suicidal act to do so—replied “ they did

not wish to die too soon.” There is also a superstition even

among the native Portuguese of Tette that if a man plants

coffee he will never afterwards be happy: they drink it, however,

and seem the happier for it.

During the drought of 1858 a neighbouring chief got

up a performance, with divers ceremonies and incantations, to

bring rain, but it would not come. The Goanese padre of

Tette, to satisfy his compatriots, appointed a procession and

prayers in honour of Saint Antonio for the same purpose. The

first attempt did not answer, but on the second occasion,

arranged to come off after the new-moon appeared, a grand

procession in the saint’s honour ended in so much rain that

the roof of the Residencia gave way: Saint Antonio’s