us to listen -with pleasure to the singing of birds. I t might

he owing to the greater cold, but the variety of notes in their

warblings seemed greater than with African birds in general.

A pretty little black bird, with white shoulders, probably a

weaver, but not seen elsewhere, sat on the topmost twigs of

the huge trees, pouring forth its melody as if glad, among

the deserted villages, once more to see the face of man. I t

flew from tree to tree, and sang on the wing, though not

soaring like the lark. I t bears frost, and to the bird-fancier

or Acclimatization Society might be an interesting addition to

their birds of song. I t is not the honey-guide alone that is

attached to man. The whydah-bird and waterwagtail are

held sacred by the natives of different parts, and consequently

come without fear close to human kind. Were our small birds

not so much persecuted by small boys, their attachment would

be more apparent, even in England.

Seabenzo, the chief whom we found on the Tyotyo

rivulet, had accompanied us some distance over the undulating

highland plains; and as he and our own men needed

meat, we killed an elephant. This, unless one really needs

the meat, or is eager for the ivory, can scarcely be- looked

back to without regret. These noble beasts, capable of being

so useful to man in the domestic state, are, we fear, destined,

at no distant date, to disappear from the face of the earth.

Yet, in the excitement, all this and more was at once forgotten,

and we joined in the assault as eagerly as those who

think only of the fat and savoury flesh.

The writings of Harris and Gordon Cumming contain such

full and nauseating details of indiscriminate slaughter of the

wild animals, that one wonders to see almost every African

book since besmeared with feeble imitations of these great

hunters’ tales. Some tell of escapes from situations which,

from our knowledge of the nature of the animals, it requires

a painful stretch of charity to believe ever existed,

even in dreams; and others of deeds which lead one to

conclude that the proportion of “ bom butchers,” in the

population, is as great as of public-house keepers to the

people in Glasgow.

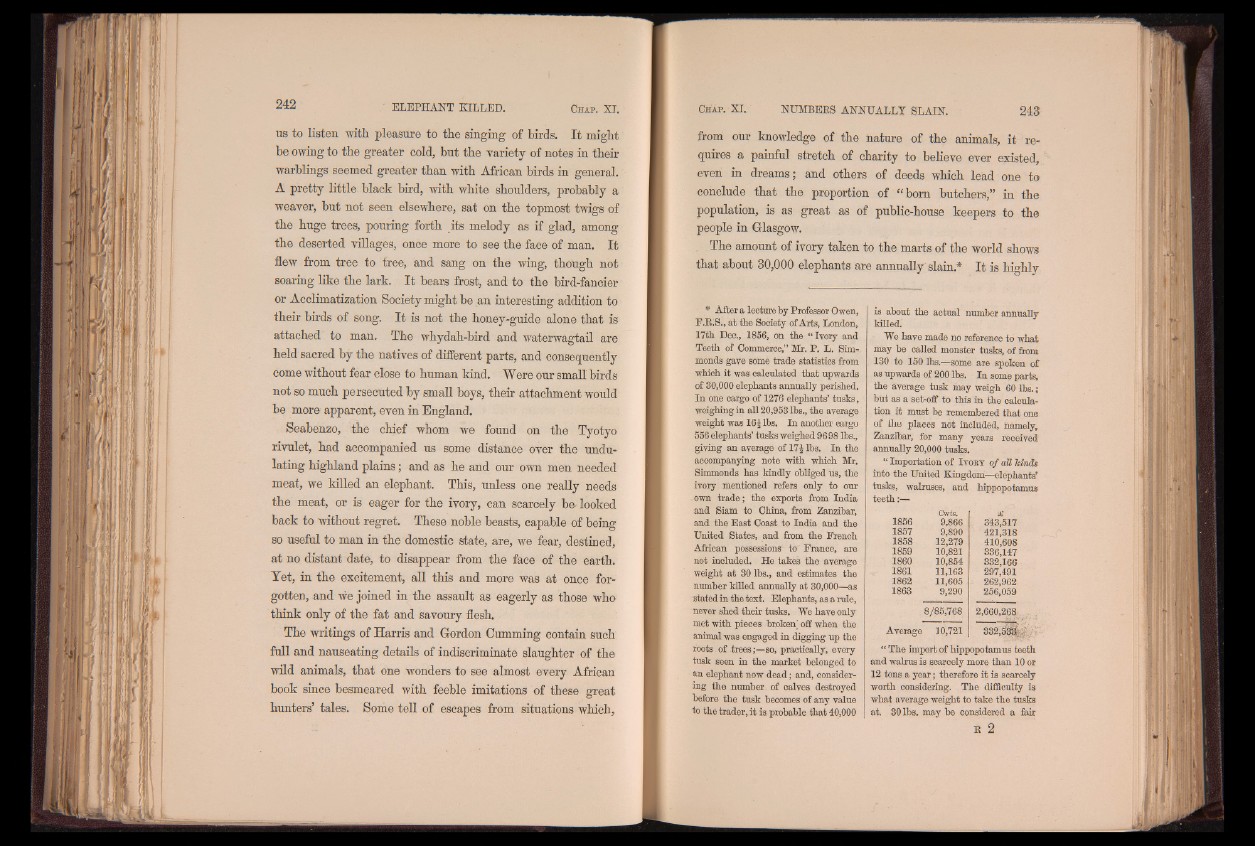

, The amount of ivory taken to the marts of the world shows

that about 30,000 elephants are annually slain.* It is highly

* After a lecture by Professor Owen,

F.R.S., at the Society of Arts, London,

17th Dec., 1856, on the “ Ivory and

Teeth of Commerce,” Mr. P. L. Sim-

monds gave some trade statistics from

which it was calculated that upwards

of 30,000 elephants annually perished.

In one cargo of 1276 elephants’ tusks,

weighing in all 20,953 lbs., the average

weight was 16$ lbs. In another cargo

556 elephants’ tusks weighed 96 98 lbs.,

giving an average of 17$ lbs. In the

accompanying note with which Mr.

Simmonds has kindly obliged us, the

ivory mentioned refers only to our

own trade; the exports from India

and Siam to China, from Zanzibar,

and the East Coast to India and the

United States, and from the French

African possessions' to France, are

not included. He takes the average

weight at 30 lbs., and estimates the

number killed annually at 30,000—as

stated in the text. Elephants, as a rule,

never shed their tusks. We have only

met with pieces broken^ off when the

animal was engaged in digging up the

roots of trees;—so, practically, every

tusk seen in the market belonged to

an elephant now dead; and, considering

the number, of calves destroyed

before the tusk becomes of any value

to the trader, it is probable that 40,000

is about the actual number annually

killed.

We have made no reference to what

may be called monster tusks, of from

130 to 150 lbs.—some are spoken of

as upwards of 200 lbs. In some parts,

the average tusk may weigh 60 lbs.;

but as a set-off to this in the calculation

it must be remembered that one

of the places not included, namely,

Zanzibar, for many years received

annually 20,000 tusks.

“ Importation of I v o b y of all kinds

into the United Kingdom—elephants’

tusks, walruses, and hippopotamus

teeth;—■

Cwts. £

1856 9,866 343,517

1857 9,890 421,318

1858 12,279 410,608

1859 10,821 336,147

1860 10,854 332,166

1861 11,163 297,491

1862 11,605 262,962

1863 9,290 256,059

8/85,768 2,660,268

Average 10,721 332,5Sf£

“ The import of hippopotamus teeth

and walrus is scarcely more than 10 or

12 tons a year; therefore it is scarcely

worth considering. The difficulty is

what average weight to take the tusks

at. 30 lbs. may be considered a fair

E 2