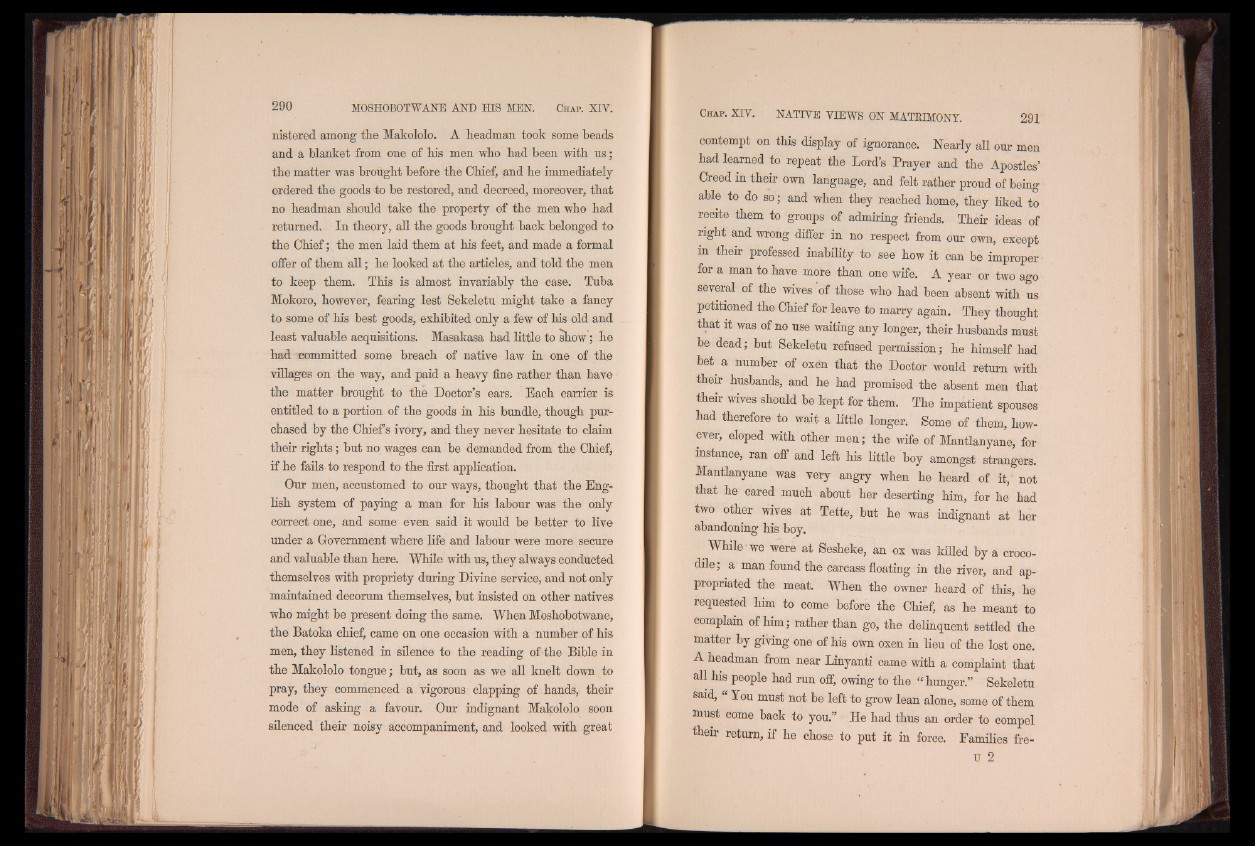

nistered among the Makololo. A headman took some beads

and a blanket from one of his men who had been with u s ;

the matter was brought before the Chief, and he immediately

ordered the goods to be restored, and decreed, moreover, that

no headman should take the property of the men who had

returned. In theory, all the goods brought back belonged to

the Chief; the men laid them at his feet, and made a formal

offer of them a ll; he looked at the articles, and told the men

to keep them. This is almost invariably the case. Tuba

Mokoro, however, fearing lest Sekeletu might take a fancy

to some of his best goods, exhibited only a few of his old and

least valuable acquisitions. Masakasa had little to show; he

had committed some breach of native law in one of the

villages on the way, and paid a heavy fine rather than have

the matter brought to the Doctor’s ears. Each carrier is

entitled to a portion of the goods in his bundle, though purchased

by the Chiefs ivory, and they never hesitate to claim

their rights; but no wages can be demanded from the Chief,

if he fails to respond to the first application.

Our men, accustomed to our ways, thought that the English

system of paying a man for his labour was the only

correct one, and some even said it would be better to live

under a Government where life and labour were more secure

and valuable than here. While with us, they always conducted

themselves with propriety during Divine service, and not only

maintained decorum themselves, but insisted on other natives

who might be present doing the same. When Moshobotwane,

the Batoka chief, came on one occasion with a number of his

men, they listened in silence to the reading of the Bible in

the Makololo tongue; but, as soon as we all knelt down to

pray, they commenced a vigorous clapping of hands, their

mode of asking a favour. Our indignant Makololo soon

silenced their noisy accompaniment, and looked with great

contempt on this display of ignorance. Nearly all our men

had learned to repeat the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostles’

Creed in their own language, and felt rather proud of being

able to do so; and when they reached home, they liked to

recite them to groups of admiring friends. Their ideas of

right and wrong differ in no respect from our own, except

in their professed inability to see how it can be improper

for a man to have more than one wife. A year or two ago

several of the wives of those who had been absent with us

petitioned the Chief for leave to marry again. They thought

that it was of no use waiting any longer, their husbands must

be dead; but Sekeletu refused permission; he himself had

be\ a Mmber of oxen that the Doctor would return with

their husbands, and he had promised the absent men that

their wives should be kept for them. The impatient spouses

had therefore to wait a little longer. Some of them, however,

eloped with other men; the wife of Mantlanyane, for

instance, ran off and left his little boy amongst strangers.

Mantlanyane was very angry when he heard of it, not

that he cared much about her deserting him, for he had

two other wives at Tette, but he was indignant at her

abandoning his boy.

While we were at Sesheke, an ox was killed by a crocodile;

a man found the carcass floating in the river, and appropriated

the meat. When the owner heard of thin, he

requested him to come before the Chief, as he meant to

complain of him; rather than go, the delinquent settled the

matter by giving one of his own oxen in lieu of the lost one.

A headman from near Linyanti came with a complaint that

all his people had run off, owing to the “ hunger.” Sekeletu

said, You must not be left to grow lean alone, some of them

must come back to you.” He had thus an order to compel

their return, if he chose to put it in force. Families freu

2