or keeled, and may, or may not, be toothed or

fringed at the mouth. A t this time it encloses the

fertilized archegonium, now developed into a sporo-

gonium, with a rudimentary pedicel, which is

enclosed within a membrane, attached at the base

and pointed at the apex, called a calyptra. This is

not to be confounded with the hood, or calyptra, in

mosses, which is torn away at the base and carried

up, like a cap or extinguisher, on the top of the

capsule. In Hepatics the calyptra remains fixed

at the base and is ruptured at the apex, leaving the

fragments behind, in the perianth, surrounding the

base of the fruit stalk. With the rupture of the

calyptra the sporogonium is forced upwards by the

growth of its peduncle, and appears above the

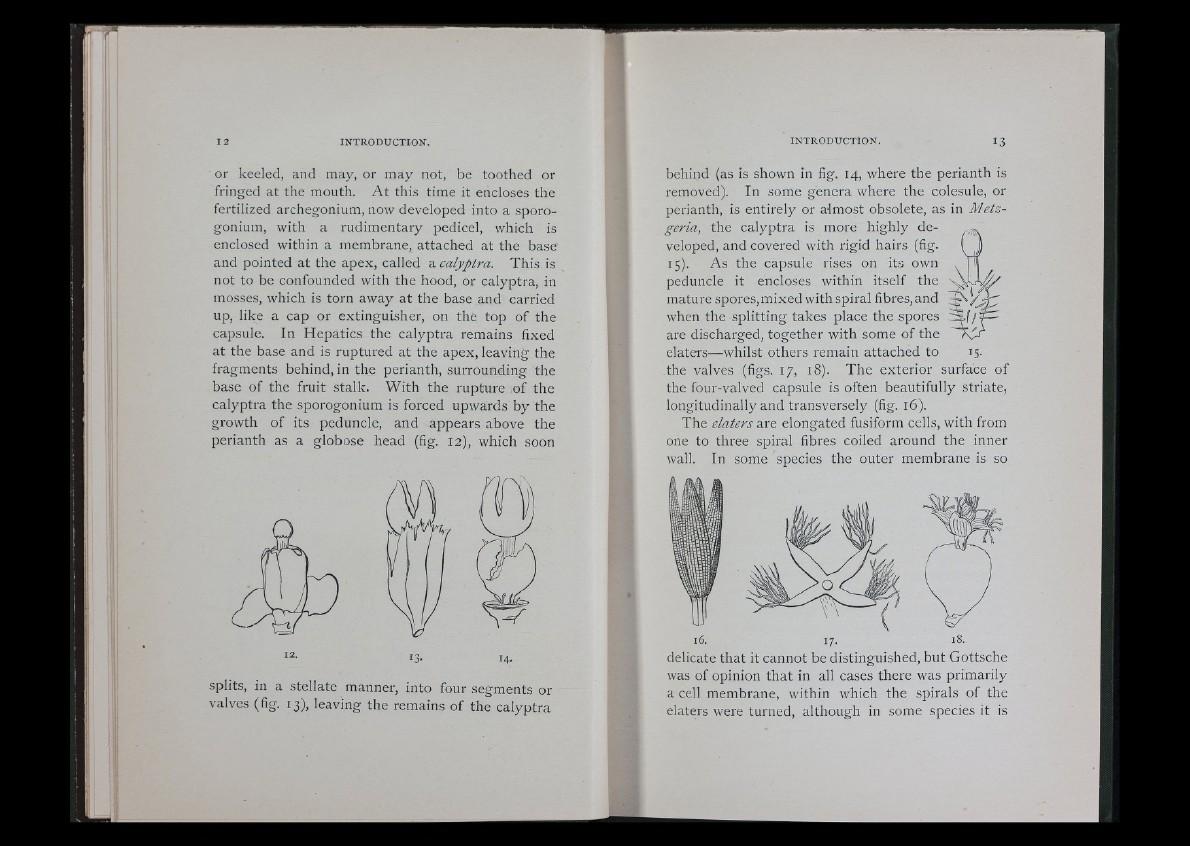

perianth as a globose head (fig. 12), which soon

splits, in a stellate manner, into four segments or

valves (fig. 13), leaving the remains of the calyptra

behind (as is shown in fig. 14, where the perianth is

removed). In some genera where the colesule, or

perianth, is entirely or almost obsolete, as in Metz-

geria, the calyptra is more highly developed,

and covered with rigid hairs (fig.

15). As the capsule rises on its own

peduncle it encloses within itself the

mature spores, mixed with spiral fibres, and

when the splitting takes place the spores

are discharged, together with some of the

elaters—-whilst others remain attached to 15.

the valves (figs. 17, 18). The exterior surface of

the four-valved capsule is often beautifully striate,

longitudinally and transversely (fig. 16).

The elaters are elongated fusiform cells, with from

one to three spiral fibres coiled around the inner

wall. In some species the outer membrane is so

delicate that it cannot be distinguished, but Gottsche

was of opinion that in all cases there was primarily

a cell membrane, within which the spirals of the

elaters were turned, although in some species it is