8 INTRODUCTION.

time.s verysmall, attached to the stem at more or less

regular distances, which are termed amphigastria, or

stipules (figs. 3 to 6). Sometimes they may resemble

the true leaves in miniature or they may be

totally different, and occasionally they are absent

altogether. Mixed with the stipules, on the ventral

surface, delicate unicellular radicles will often be

observed, which assist in fixing the Hepatic to its

matrix or the mosses with which it is intermixed.

Theoretically three rows of leaves are present, two

lateral, or true leaves, and one ventral, the stipules

or amphigastria, the radicles may be regarded

morphologically as modified leaves.

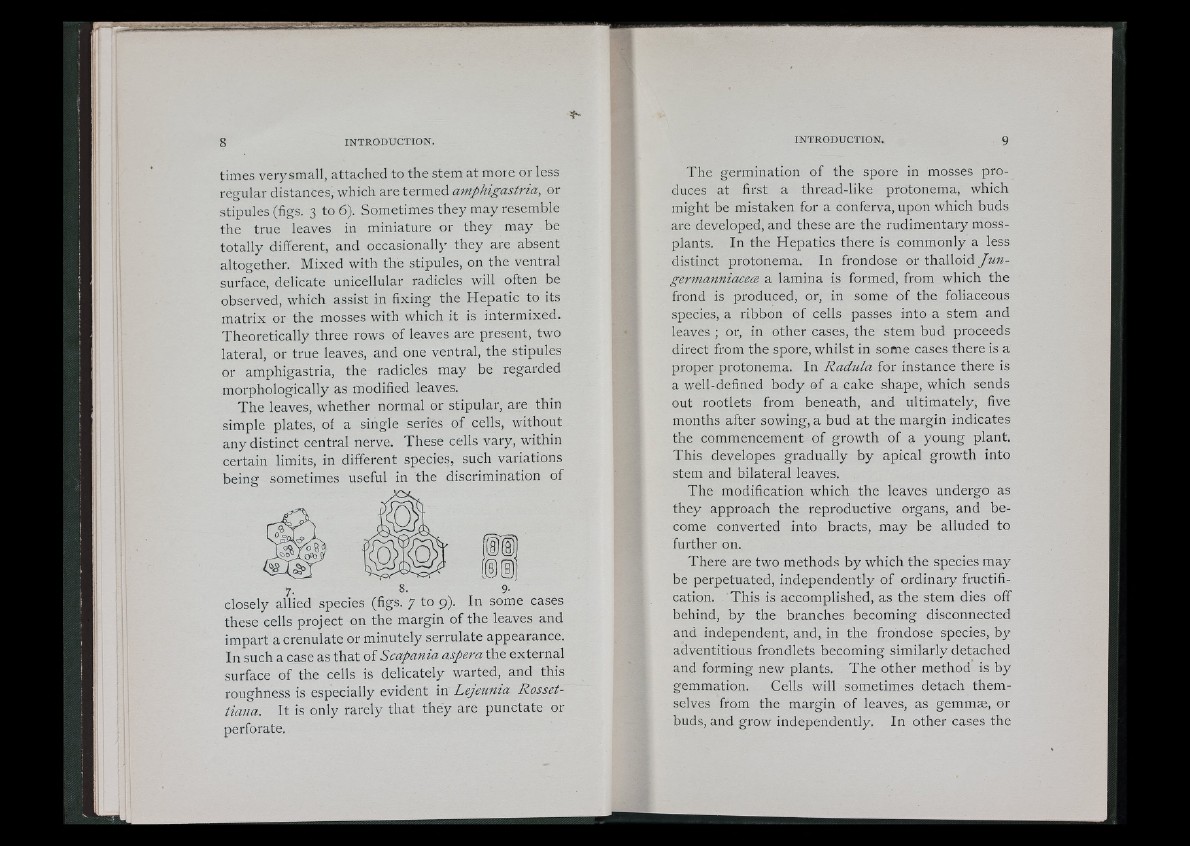

The leaves, whether normal or stipular, are thin

simple plates, of a single series of cells, without

any distinct central nerve. These cells vary, within

certain limits, in different species, such variations

being sometimes useful in the discrimination of

7. 8- 9 '

closely allied species (figs. 7 to 9). In some cases

these cells project on the margin of the leaves and

impart acrenulate or minutely serrulate appearance.

In such a case as that of Scapania aspera the external

surface of the cells is delicately warted, and this

roughness is especially evident in Lejeunia Rosset-

tiana. It is only rarely that they are punctate or

perforate.

The germination of the spore in mosses produces

at first a thread-like protonema, which

might be mistaken for a conferva, upon which buds

are developed, and these are the rudimentary moss-

plants. In the Hepatics there is commonly a less

distinct protonema. In frondose or thalloid Ju n germanniacecB

a lamina is formed, from which the

frond is produced, or, in some of the foliaceous

species, a ribbon of cells passes into a stem and

leaves ; or, in other cases, the stem bud proceeds

direct from the spore, whilst in some cases there is a

proper protonema. In Radula for instance there is

a well-defined body of a cake shape, which sends

out rootlets from beneath, and ultimately, five

months after sowing, a bud at the margin indicates

the commencement of growth of a young plant.

This developes gradually by apical growth into

stem and bilateral leaves.

The modification which the leaves undergo as

they approach the reproductive organs, and become

converted into bracts, may be alluded to

further on.

There are two methods by which the species may

be perpetuated, independently of ordinary fructification.

This is accomplished, as the stem dies off

behind, by the branches becoming disconnected

and independent, and, in the frondose species, by

adventitious frondlets becoming similarly detached

and forming new plants. The other method is by

gemmation. Cells will sometimes detach themselves

from the margin of leaves, as gemmae, or

buds, and grow independently. In other cases the