As a rule, the Pokomo were friendly and easily convinced

of our good intentions; but at times we met with

difficulty in procuring guides. Along the banks of the

Tana, except at points where the natives had made

clearings, the forest growth was really picturesque and

imposing. The Pokomo have a slight knowledge of

irrigation, and in their little openings in the forest an

idea can be had of the productiveness of the soil, and

what might be accomplished by cultivation of the soil, if

European methods were in vogue. This, however, is

only in the immediate neighbourhood of the river; for at

distances varying from 100 yards to one mile from the

banks of the river, the aspect changes mto that of a

sandy desert, gleaming here and there with mica. Such

trees as are found on this desert are stunted mimosa

and aloes.

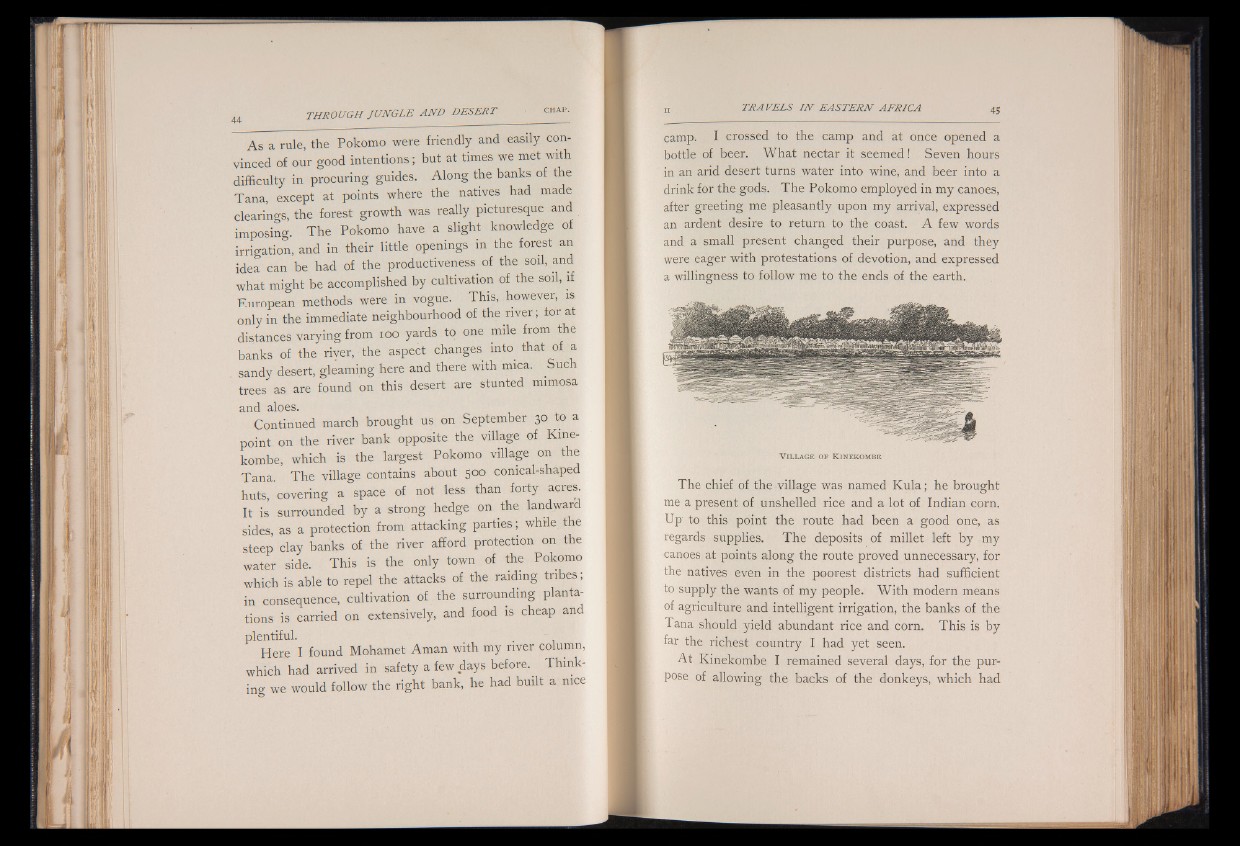

Continued march brought us on September 30 to a

point on the river bank opposite the village of Kine-

kombe, which is the largest Pokomo village on the

Tana. The village contains about 500 conical-shaped

huts, covering a space of not less than forty acres.

It is surrounded by a strong hedge on the landward

sides, as a protection from attacking parties; while the

steep clay banks of the river afford protection on the

water side. This is the only town of the Pokomo

which is able to repel the attacks of the raiding tribes;

in consequence, cultivation of the surrounding plantations

is carried on extensively, and food is cheap and

plentiful.

Here I found Mohamet Aman with my river column,

which had arrived in safety a few days before.^ Thinking

we would follow the right bank, he had built a nice

camp. I crossed to the camp and at once opened a

bottle of beer. What nectar it seemed! Seven hours

in an arid desert turns water into wine, and beer into a

drink for the gods. The Pokomo employed in my canoes,

after greeting me pleasantly upon my arrival, expressed

an ardent desire to return to the coast. A few words

and a small present changed their purpose, and they

were eager with protestations of devotion, and expressed

a willingness to follow me to the ends of the earth.

V i l l a g e o f K in e k o m b e

The chief of the village was named K ula ; he brought

me a present of unshelled rice and a lot of Indian corn.

Up to this point the route had been a good one, as

regards supplies. The deposits of millet left by my

canoes at points along the route proved unnecessary, for

the natives even in the poorest districts had sufficient

to supply the wants of my people. With modern means

of agriculture and intelligent irrigation, the banks of the

Tana should yield abundant rice and corn. This is by

far the richest country I had yet seen.

At Kinekombe I remained several days, for the purpose

of allowing the backs of the donkeys, which had