As we marched along, all the Wakamba we met

appeared sullen, and the guides we had taken with us

said that they would surely come at night and rescue

the slaves. A t the end of the day’s march we camped

in a small valley, and all night long our sleep was

broken by continued shouting and bawling of war-

songs. The natives of the neighbouring villages came

to us hour by hour, each bringing a small présent of

milk, or perhaps a goat. This they did from fear

that if we were attacked by the natives, and they

had not previously made friendly overtures, we would

wreak vengeance upon them. They said that all the

inhabitants of the villages of Mwyru were encamped

near us, and vowed to fall upon us and take back the

slaves. However, the demonstration amounted to nothing

but bluster.

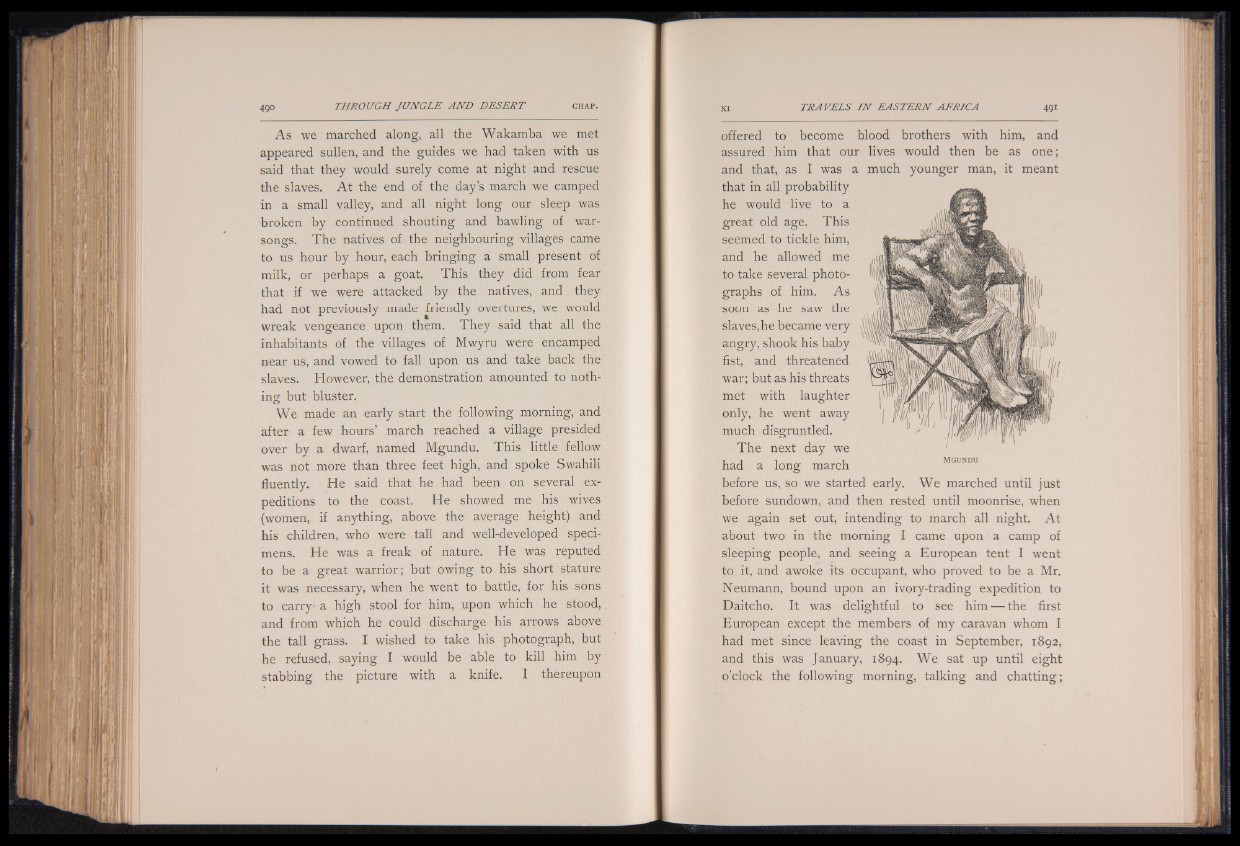

We made an early start the following morning, and

after a few hours’ march reached a village presided

over by a dwarf, named Mgundu. This little fellow

was not more than three feet high, and spoke Swahili

fluently. He said that he had been on several expeditions

to the coast. He showed me his wives

(women, if anything, above the average height) and

his children, who were tall and well-developed specimens.

He was a freak of nature. He was reputed

to be a great warrior; but owing to his short stature

it was necessary, when he went to battle, for his sons

to carry a high stool for him, upon which he stood,

and from which he could discharge his arrows above

the tall grass. I wished to take his photograph, but

he refused, saying I would be able to kill him by

stabbing the picture with a knife. I thereupon

offered to become blood brothers with him, and

assured him that our lives would then be as one;

and that, as I was a much younger man, it meant

that in all probability

he would live to a

great old age. This

seemed to tickle him,

and he allowed me

to take several photographs

of him. As

soon as he saw the

slaves, he became very

angry, shook his baby

fist, and threatened

war; but as his threats

met with laughter

only, he went away

much disgruntled.

The next day we

t i t 1 M g u n d u had a long march

before us, so we started early. We marched until just

before sundown, and then rested until moonrise, when

we again set out, intending to march all night. A t

about two in the morning I came upon a camp of

sleeping people, and seeing a European tent I went

to it, and awoke its occupant, who proved to be a Mr.

Neumann, bound upon an ivory-trading expedition to

Daitcho. It was delightful to see him — the first

European except the members of my caravan whom I

had met since leaving the coast in September, 1892,

and this was January, 1894. We sat up until eight

o’clock the following morning, talking and chatting;