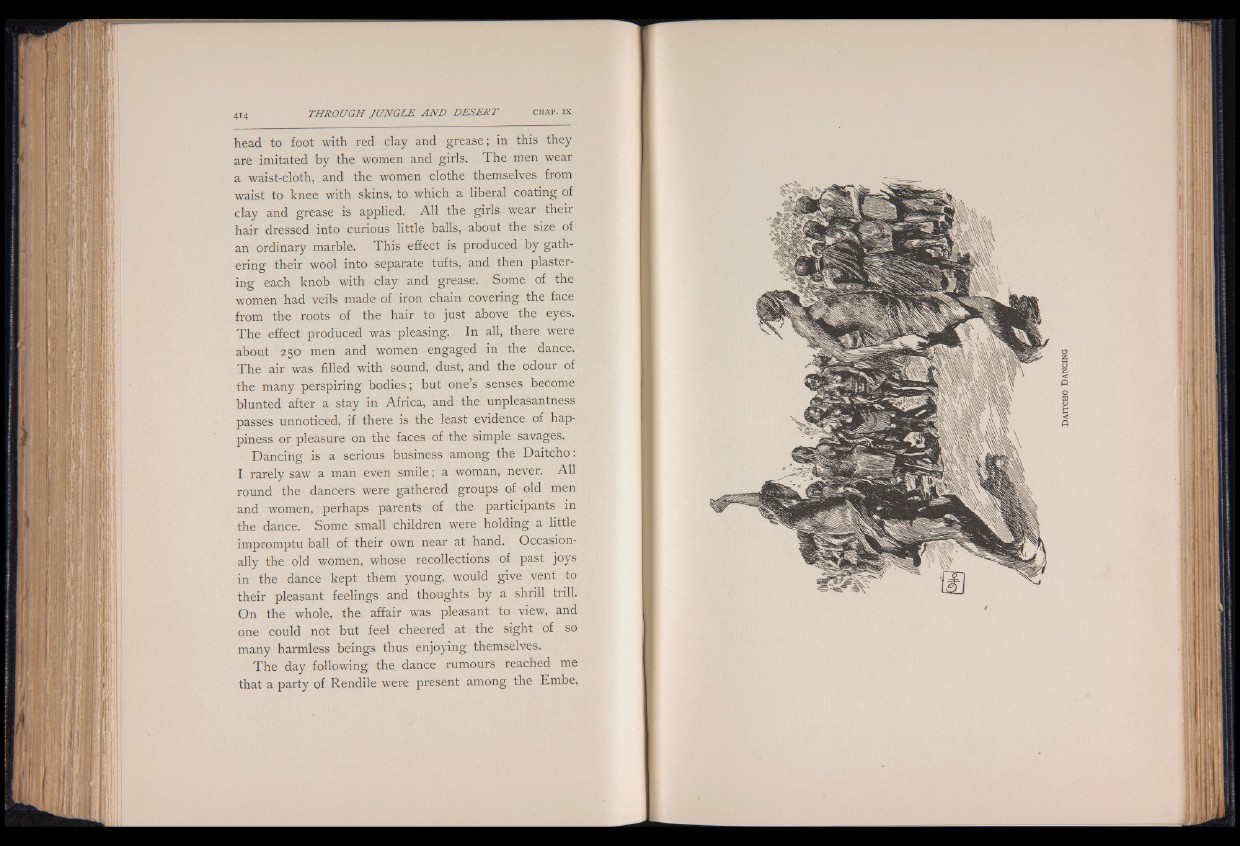

head to foot with red clay and grease; in this they

are imitated by the women and girls. The men wear

a waist-cloth, and the women clothe themselves from

waist to knee with skins, to which a liberal coating of

clay and grease is applied. All the girls wear their

hair dressed into curious little balls, about the size of

an ordinary marble. This effect is produced by gathering

their wool into separate tufts, and then plastering

each knob with clay and grease. Some of the

women had veils made of iron chain covering the face

from the roots of the hair to just above the eyes.

The effect produced was pleasing. In all, there were

about 250 men and women engaged in the dance.

The air was filled with sound, dust, and the odour of

the many perspiring bodies; but one’s senses become

blunted after a stay in Africa, and the unpleasantness

passes unnoticed, if there is the least evidence of happiness

or pleasure on the faces of the simple savages.

Dancing is a serious business among the Daitcho:

I rarely saw a man even smile; a woman, never. All

round the dancers were gathered groups of old men

and women, perhaps parents of the participants in

the dance. Some small children were holding a little

impromptu ball of their own near at hand. Occasionally

the old women, whose recollections of past joys

in the dance kept them young, would give vent to

their pleasant feelings and thoughts by a shrill trill.

On the whole, the affair was pleasant to view, and

one could not but feel cheered at the sight of so

many harmless beings thus enjoying themselves.

The day following the dance rumours reached me

that a party of Rendile were present among the Embe,