i

it a

Ii

i f

i i

all 410,743 pots of spirits. This, estimating the

grown-up male population at 10,000, is an allowance

of 41 pots to each'individual.

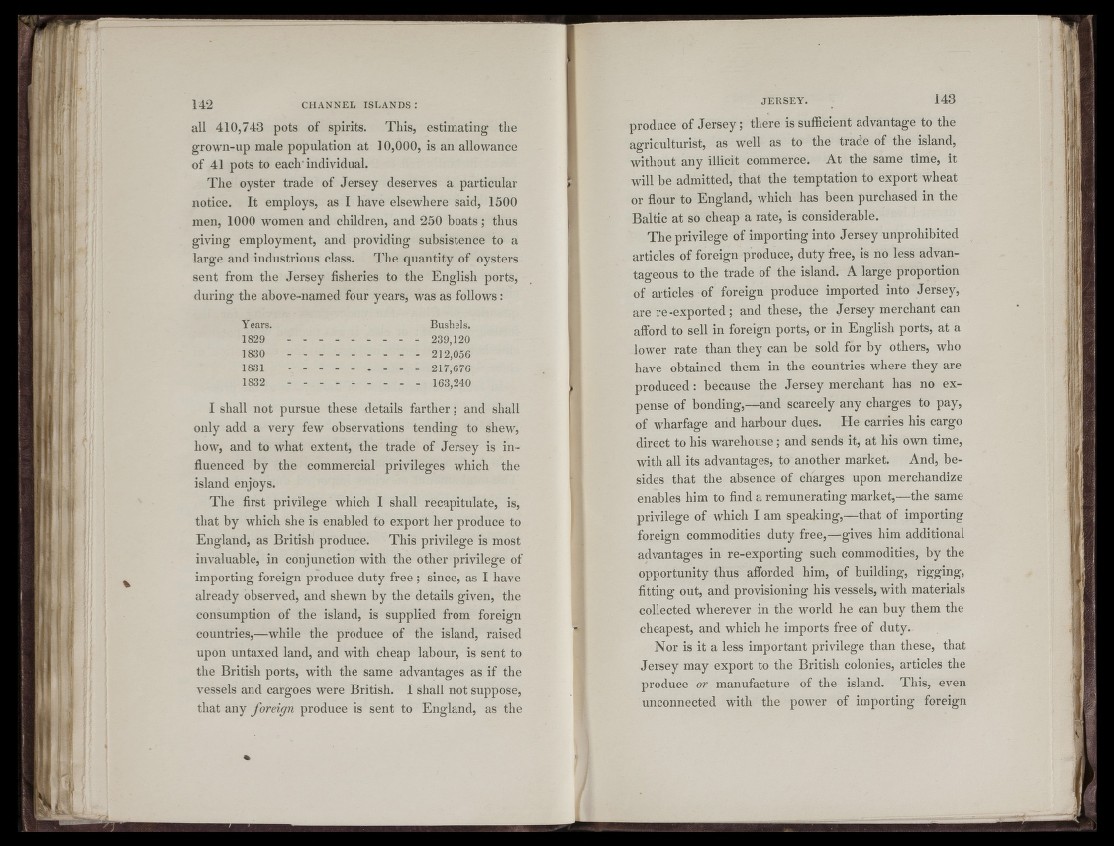

The oyster trade of Jersey deserves a particular

notice. It employs, as I have elsewhere said, 1500

men, 1000 women and children, and 250 boats; thus

giving employment, and providing subsistence to a

large and industrious class. The quantity of oysters

sent from the Jersey fisheries to the English ports,

during the above-named four years, was as follows:

Years. Bushels.

1829 - - - - ............................. 239,120

1830 212,056

1831 - - ............................................ 217,676

1832 - - - .................................... 163,240

I shall not pursue these details farther; and shall

only add a very few observations tending to shev^,

how, and to what extent, the trade of Jersey is in-

fiuenced by the commercial privileges which the

island enjoys.

The first privilege which I shall recapitulate, is,

that by which she is enabled to export her produce to

England, as British produce. This privilege is most

invaluable, in conjunction with the other privilege of

importing foreign produce duty fre e ; since, as I have

already observed, and shewn by the details given, the

consumption of the island, is supplied from foreign

countries,—while the produce of the island, raised

upon untaxed land, and with cheap labour, is sent to

the British ports, with the same advantages as if the

vessels and cargoes were British. I shall not suppose,

that any foreign produce is sent to England, as the

produce of Jersey; there is sufficient advantage to the

agriculturist, as well as to the trade of the island,

without any illicit commerce. At the same time, it

will be admitted, that the temptation to export wheat

or flour to England, which has been purchased in the

Baltic at so cheap a rate, is considerable.

The privilege of importing into Jersey unprohibited

articles of foreign produce, duty free, is no less advantageous

to the trade of the island. A large proportion

of articles of foreign produce imported into Jersey,

are re-exported; and these, the Jersey merchant can

aiford to sell in foreign ports, or in English ports, at a

lower rate than they can be sold for by others, who

have obtained them in the countries where they are

produced : because the Jersey merchant has no expense

of bonding,—and scarcely any charges to pay,

of wharfage and harbour dues. He carries his cargo

direct to his warehouse; and sends it, at his own time,

with all its advantages, to another market. And, besides

that the absence of charges upon merchandize

enables him to find a remunerating market,—the same

privilege of which I am speaking,—that of importing

foreign commodities duty free,—gives him additional

advantages in re-exporting such commodities, by the

opportunity thus aiforded him, of building, rigging,

fitting out, and provisioning his vessels, with materials

collected wherever in the world he can buy them the

cheapest, and which he imports free of duty.

Nor is it a less important privilege than these, that

Jersey may export to the British colonies, articles the

produce or manufacture of the island. This, even

unconnected with the power of importing foreign

Ii