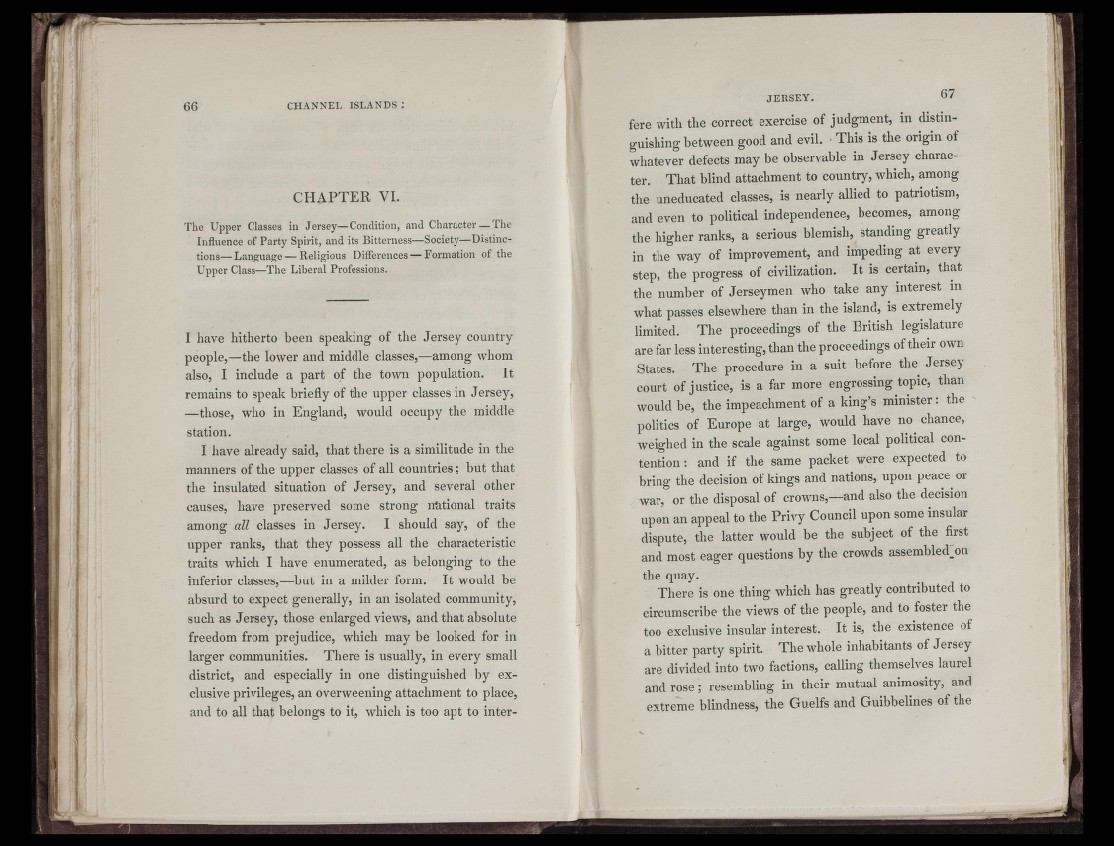

C H A P T ER VI.

The Upper Classes in Jersey—Condition, and Character— The

Influence of Party Spirit, and its Bitterness—Society—Distinctions—

Language — Religious Differences — Formation of the

Upper Class—The Liberal Professions.

I have hitherto been speaking of the Jersey country

people,—the lower and middle classes,—among whom

also, I include a part of the town population. It

remains to speak briefly of the upper classes in Jersey,

—those, who in England, would occupy the middle

station.

I have already said, that there is a similitude in the

manners of the upper classes of all countries; but that

the insulated situation of Jersey, and several other

causes, have preserved some strong national traits

among all classes in Jersey. I should say, of the

upper ranks, that they possess all the characteristic

traits which I have enumerated, as belonging to the

inferior classes,—but in a milder form. It would be

absurd to expect generally, in an isolated community,

such as Jersey, those enlarged views, and that absolute

freedom from prejudice, which may be looked for in

larger communities. There is usually, in every small

district, and especially in one distinguished by exclusive

privileges, an overweening attachment to place,

and to all that belongs to it, which is too apt to interfere

with the correct exercise of judgment, in distinguishing

between good and evil. ■ This is the origin of

whatever defects may be observable in Jersey character.

That blind attachment to country, which, among

the uneducated classes, is nearly allied to patriotism,

and even to political independence, becomes, among

the higher ranks, a serious blemish, standing greatly

in the way of improvement, and impeding at every

step, the progress of civilization. It is certain, that

the number of Jerseymen who take any interest in

what passes elsewhere than in the island, is extremely

limited. The proceedings of the British legislature

are far less interesting, than the proceedings of their own

States. The procedure in a suit before the Jersey

court of justice, is a far more engrossing topic, than

would be, the impeachment of a king’s minister : the

politics of Europe at large, would have no^ chance,

weighed in the scale against some local political contention

: and if the same packet were expected to

bring the decision of kings and nations, upon peace or

war, or the disposal of crowns,—and also the decision

upon an appeal to the Privy Council upon some insular

dispute, the latter would be the subject of the first

and most eager questions by the crowds assembled^on

the quay.

There is one thing whicli has greatly contributed to

circumscribe the views of the people, and to foster the

too exclusive insular interest. It is, the existence of

a bitter party spirit. The whole inhabitants of Jersey

are divided into two factions, calling themselves laurel

and rose ; resembling in their mutual animosity, and

extreme blindness, the Guelfs and Guibbelines of the