a ■

iJ..' 1 :

'N-': Î

! i

< I

the rock wliicli is formed by tbe consolidation of tbe

sand, so tliat ive liave often repeated again and again

in tlie distance of a quarter of a mile all tlie pbeno-

meua,—denudation, uncoiiformability, curving, fold-

ing, synclinal and anticlinal axes, &c., wbicb are

[irodnced in real rocks, if I may use tbe expression,

by combined aqueous and nietamorpbic action,

extending over incalculable periods of time. Tbe

principal roads, ndiicli are extremely good as tliey are

laid out and iiiaiiitaiiied partly ivitli a view to

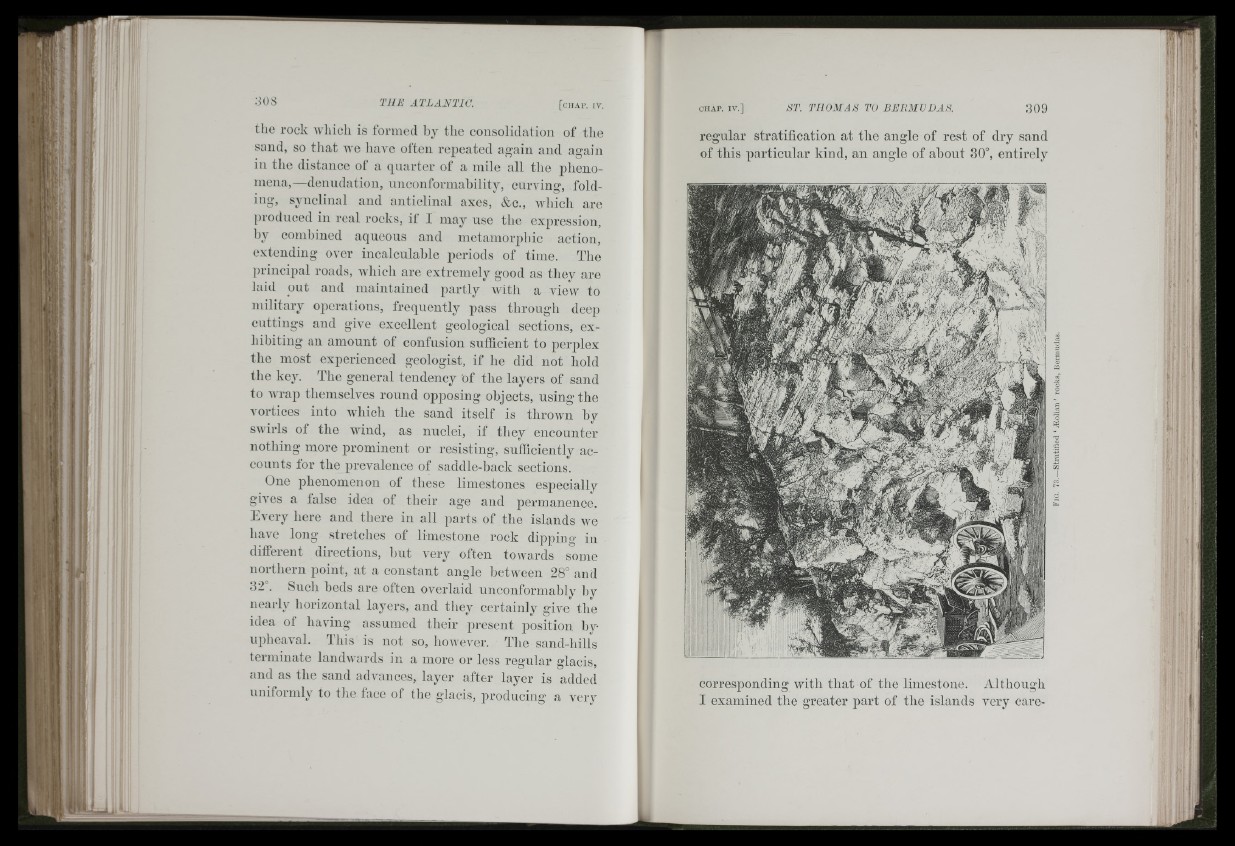

military operations, frequently pass tbrougb deep

cuttings and give excellent geological sections, exhibiting

an amount of confusion sufficient to perplex

tbe most experienced geologist, if be did not liold

tbe kcA. file general tendency of tbe layers of sand

to n rap tbemselves round opposing objects, using the

vortices into wbicb the sand itself is thrown by

swirls of tbe wind, as nuclei, if they encounter

nothing more prominent or resisting, sufficiently accounts

for tbe prevalence of saddle-back sections.

One ¡^benomenon of these limestones especially

gives a false idea of their age and permanence.

Every here and there in all parts of the islands we

have long stretches of limestone rock dipping in

different directions, hut very often towards some

northern point, at a constant angle between 28° and

32 . Sucli beds are often overlaid unconformahly by

nearly horizontal layers, and tliey certainly give the

idea of having assumed tbeir present position by

npbeaA’al. Tbis is not so, however. Tbe sand-bills

terminate landwards in a more or less regular glacis,

and as tbe sand adi'ances, layer after layer is added

uniformly to the face of tbe glacis, producing a very

regular stratification at the angle of rest of dry sand

of this particular kind, an angle of ahout 30°, entirely

corresponding with that of the limestone. Although

I examined the greater part of the islands very care