f

[>li X

i

“■’I ;

■-M

live at extreme depths, simply because it exhibits no trace of active vitality after

being dragged from a normal to an abnormal element.

Again, false analogies were advanced to show what would be the effect

of the stupendous pressure known to prevail at the bottom of the ocean on

creatures constituted to exist under a totally different series of conditions.

Thus, the collapse of the air-bladder in some fishes, the disembowelment of

others, the inconvenience experienced by persons when carried down only a few

fathoms in the diving-bell, the long and arduous training undergone by the

pearl-fisher, the hacloieyed experiments on submerged logs of wood and legs of

mutton, and, lastly, the fact that limestone could be fused under the pressure

present without parting with its carbonic acid, have one and all been more or

less emphatically dwelt on and handed down from writer to writer, until, like a

troubled dream which the mind finds it diificult to shake off, a fictitious belief

in the analogy of the cases was engendered.

To air-breathing terrestrial animals the diminution of pressure accompanying

increase of elevation above the sea-level stands in the same relation as the

increase of pressure attendant on augmented depth does to water-breathing

creatures in the ocean. Every one is aware that, at the level of the sea, the

pressui’e of the atmospheric column upon every square inch of surface is equal to

14J lbs., and, hence, that the pressure distributed over the body of an averagesized

man amounts to about 33,600 lbs., or nearly 15 tons. Now, since at an

elevation of 18,480 feet the weight of the superincumbent column is reduced

one-half, according to the law of the expansion of gases, these 14J lbs. would be

reduced to —a degree of rarefication which is constantly undergone by

travellers without danger and but a very moderate degree of inconvenience if

gradually encountered, and not greatly in excess of that present in the great

mountain-ranges of tropical America and Asia, where we meet with flourishing

cities and villages, surrounded by abundant cultivation*. I t is obvious, therefore,

that the human frame, endowed as it is with an unparalleled degree of complexity

and susceptibility to external conditions, may nevertheless thrive for any

length of time in an atmosphere so rarefied that the too abrupt transition to

it from the sea-level would be attended with serious if not fatal consequences.

* Quito is situated at an elevation of 10,000 ft. above the sea-level. The Potosi mines, on the tableland

of Bolivia, occur a t 16,000 ft. Some passes in the Himalayah have an elevation of 20,000 ft.

In the Condor of the Andes we have a notable example of the power

possessed by the Vultures to accommodate themselves to rapid changes of atmospheric

pressure. Humboldt describes this bird as soaring for protracted periods

at an elevation of 18,000 feet; and it is known to live and breed at from 10,000

to 15,000 feet. I have myself seen the common Eagle of the Himalayas soaring

for hours at very little short of the same height. Fishes abound in mountain-

lakes up to 13,000 feet; whilst there is no elevation, short of the limit of

perpetual snow, at which the microscopic forms both of the animal and vegetable

kingdoms do not habitually live; and it is highly probable that, in the latter

case, it is the diminution of temperature, and not the increase of rarefaction of

the atmosphere, which determines their ascending limit.

Again, plants flourish at very great heights. In Chili and Peru, wheat grows

abundantly up to 13,000 feet; in Mexico, the limit of trees and shrubs is said

to be 13,000 feet also ; whilst in the Himalayas, as recorded by Captain Gerard,

the Genista, a kind of broom, is to be met with at from 17,000 to 18,000 feet

above the level of the sea.

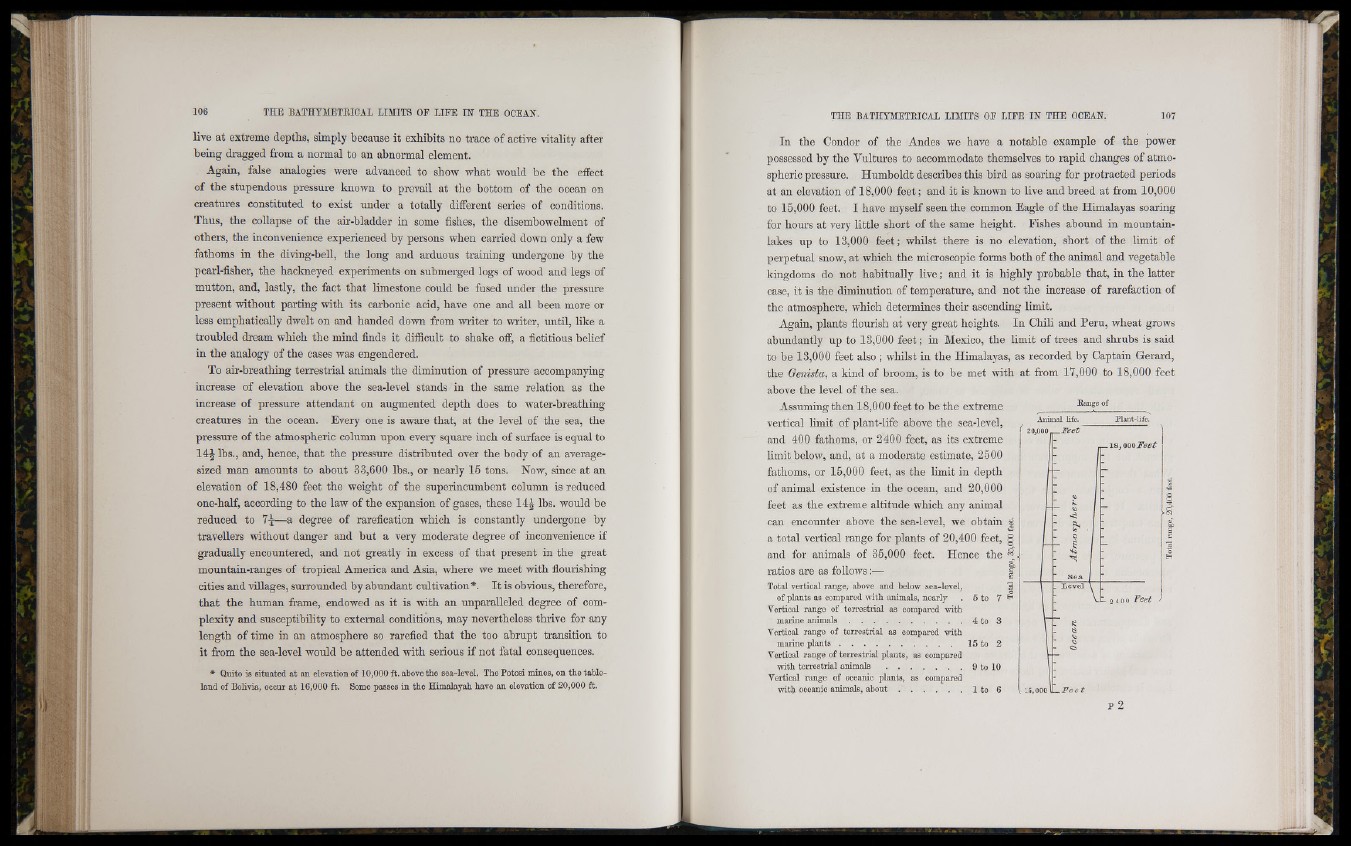

Assuming then 18,000 feet to be the e x t r e m e ______ ____________

vertical limit of plant-life above the sea-level,

and 400 fathoms, or 2400 feet, as its extreme

limit below, and, at a moderate estimate, 2500

fathoms, or 15,000 feet, as the limit in depth

of animal existence in the ocean, and 20,000

feet as the extreme altitude which any animal

can encounter above the sea-level, we obtain | i

a total vertical range for plants of 20,400 feet, |

and for animals of 35,000 feet. Hence the '

ratios are as follows;—

Total vertical range, above and below sea-level,

of plants as compared with animals, nearly . 5 to 7 '

Vertical range of terrestrial as compared with

marine a n im a l s ...................................................4 to 3

Vertical range of terrestrial as compared with

marine p l a n t s 15 to 2

Vertical range of terrestrial plants, as compared

with terrestrial a n im a l s .................................. 9 to 10

Vertical range of oceanic plants, as compared

Avith oceanic animals, a b o u t .............................1 to 6