the southward as to overpower and deflect that portion of the stream which bears

the drift-timber across.

Aug. 12.—Whatever may be the aspect of Greenland in its winter garb, or

under lowering skies, it is a very enjoyable place on a bright day in August.

Notwithstanding the scanty nature of the vegetation, there is quite enough

verdure observable to soften the asperities of the landscape, whilst the brilliant

sun and piu’e atmosphere impart a degree of warmth to its colouring that is

heightened, instead of being destroyed, by the cold whiteness of the ice-covered

fiords.

The quantity of ice is somewhat less today; but it fluctuates so rapidly as it

happens to be influenced either by the -wind or tide, that it is impossible to

foretell one houi* what may be the state of the fiords the next. Yesterday the

pack streamed in so suddenly, that a large party of the Danish residents who had

come round from the colony, by boat, to visit the ship, were obliged to make

their way home in the dark, across a mile of heavy swamp.

The temperature in the middle of the day is producing marked effects on the

ice. On every side the ear catches the sound of the melted drops as they trickle

from the projecting ledges into the -water. Many of the pieces seem akeady to

be honey-combed, and break up when subjected to pressure by the surrounding

masses, the immediate alteration in their centres of gravity causing them to turn

over and set the whole of the neighbouiing pieces in motion. This is probably

the reason why disintegration, when it has once commenced, goes on so rapidly,

and even continues for some time after the midday heat is over; for the temperature

of the air does not rise above 64° Fahr., and the water of the fiord is

too cold to admit of the hand being plunged in it for many minutes without

causing acute pain.

The great depth of the fiords constitutes one of their most striking characteristics.

During my attempts to dredge, I rarely met with less than 20 fathoms

close to the shore, whilst as the centre of the fiords was approached it ranged

from that up to 150 fathoms. At one portion of the large hay stretching across

from Hernhutt towards the sea the di-edge was let go in 200 fathoms, and from

that great depth brought up a number of Sea Urchins {Echinus Sphoira).

But the depth was by no means the only obstacle to the use of the dredge.

The powerful tide, the quantities of drifting ice, and the nature of the bottom,

which seems to consist almost entirely of boulders, all tended to render it both

tedious and hazardous; and on more than one occasion I had cause to be

thankful that, during my endeavours to clear the dredging-line from the large

masses of ice that continually drifted against and fouled it, their sudden

plunging over did not send my small crew and myself on a sounding expedition

for which we were but ill prepared.

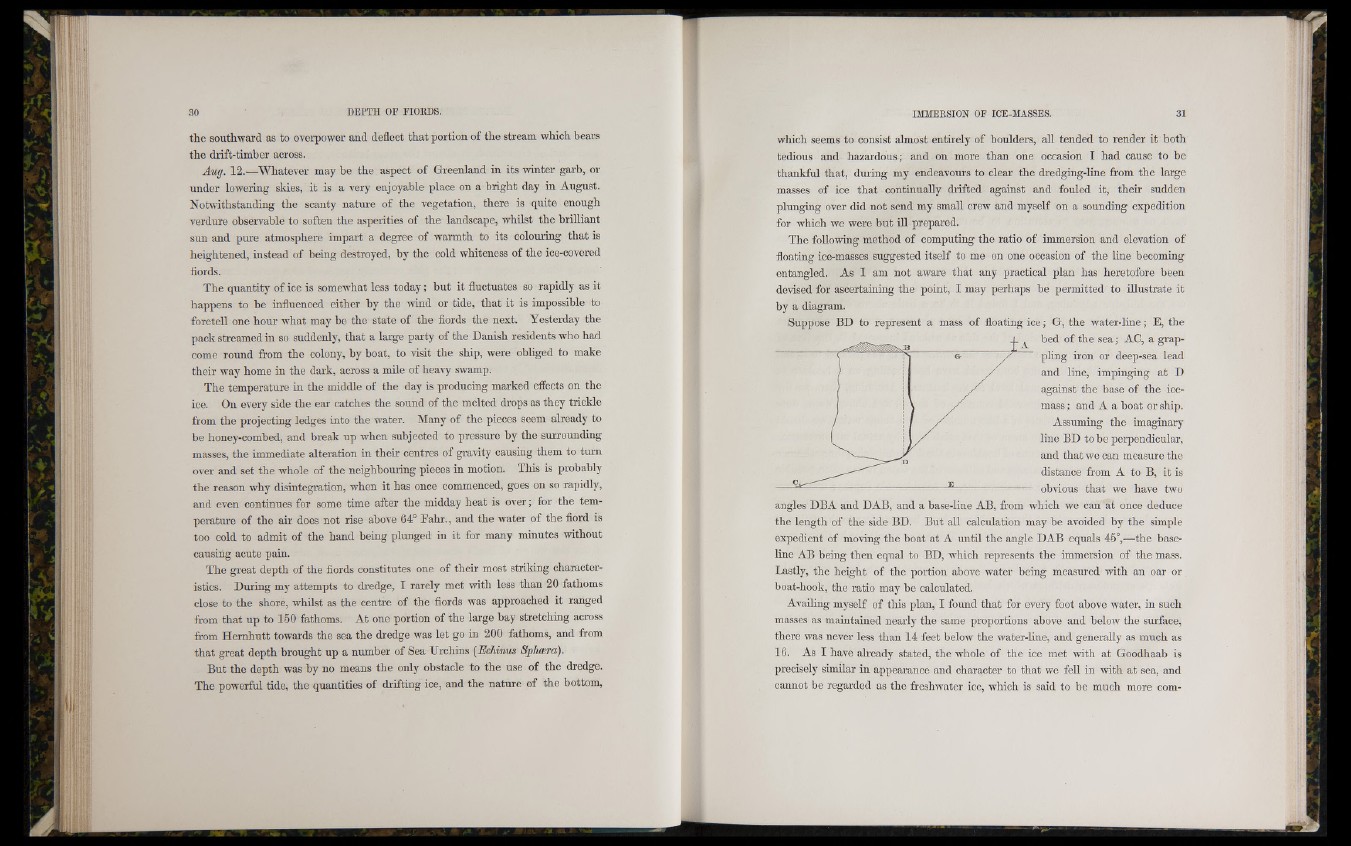

The following method of computing the ratio of immersion and elevation of

floating ice-masses suggested itself to me on one occasion of the line becoming

entangled. As I am not aware that any practical plan has heretofore been

devised for ascertaining the point, I may perhaps be permitted to illustrate it

by a diagram.

Suppose BD to represent a mass of floating ic e ; G, the water-line; E, the

^ ^ bed of the sea; AC, a grappling

iron or deep-sea lead

and line, impinging at D

against the base of the ice-

mass ; and A a boat or ship.

Assuming the imaginary

line BD to be perpendicular,

and that we can measure the

distance from A to B, it is

ob-vious that we have two

5 DBA and DAB, and a base-line AB, from which we can at once deduce

the length of the side BD. But all calculation may be avoided by the simple

expedient of moving the boat at A until the angle DAB equals 45'’,—the baseline

AB being then equal to BD, which represents the immersion of the mass.

Lastly, the height of the portion above water being measured with an oar or

boat-hook, the ratio may be calculated.

Availing myself of this plan, I found that for every foot above water, in such

masses as maintained nearly the same proportions above and below the surface,

there was never less than 14 feet below the water-line, and generally as much as

16. As I have already stated, the whole of the ice met with at Goodhaab is

precisely similar in appearance and character to that we fell in -with at sea, and

cannot be regarded as the freshwater ice, which is said to be much more com