the recession of the water at the close of the warm season, might germinate and

gradually spread themselves.

Supposing the above theory to be admissible, it would throw some light on the

cave deposits and remains. In the event of herds of animals, such as reindeer,

congregating together in these subglacial valleys, should their egress be prevented

by the collapse of portions of the glacier, or the sudden irruption of floods, they

would be swept away with the current, and their remains imbedded in the

drift-bed, such as escaped into the more elevated crevices and caves (which

are nowhere more abundant than in the rock formation of South Greenland)

dying there, and being after a time covered over with detritus.

Where the Ruminants had penetrated, the indigenous Carnivora would follow,

and thus the remains of both orders might become mixed up in the same localities ;

whilst the drift-beds formed at the mouths of the valleys would become the

receptacle for the remains of the entire local fauna of the period, terrestrial as

well as marine.

Lastly, this view would tend to show that the deep furrows which occur on

the upper surface of the ancient drift-beds and are generally found filled up with

a muddy deposit, had been formed by the transit of ice-bergs, the traces of

previously formed furrows having become obliterated by the gradual subsidence

of gravel in lieu of the lighter mud originally occupying them.

Before closing my observations on icebergs, I would allude to an occurrence

which, although at first sight paradoxical, admits of a very simple explanation.

I t must have fallen under notice again and again ; but as it bears materially on

the safety of submerged telegraphic cables, and has not been taken into consideration

in connexion with that subject, I may be permitted to illustrate it. I

allude to the case of bergs which require deeper water for their flotation, after

being diminished in bulk by the breaking away of a portion, than they did previously,

and the consequent possibility of their grounding and inflicting injury

on a cable after having floated innocuously over the spur or shoal which is supposed

to divert all bergs of sufficient volume to ground within the barrier. The

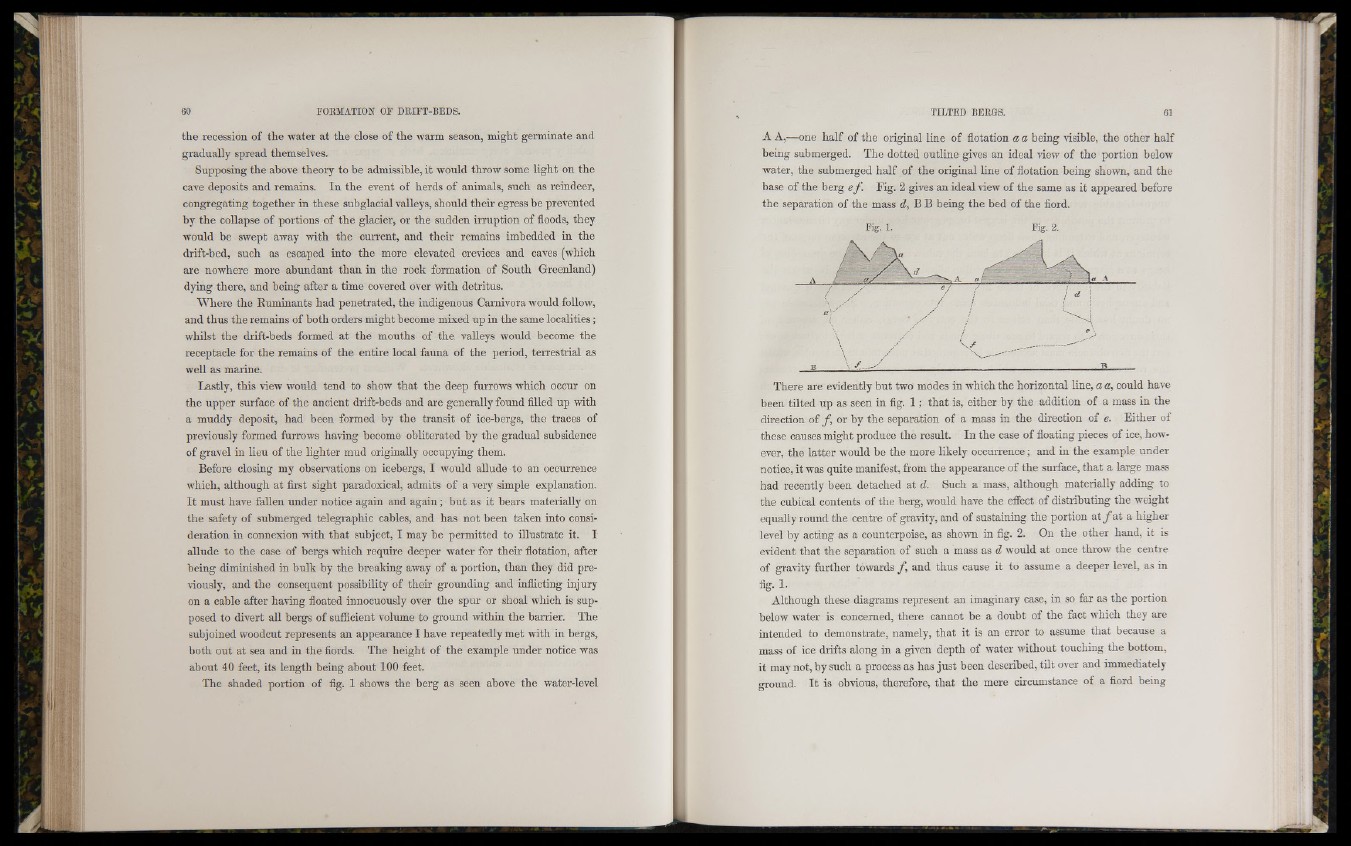

subjoined woodcut represents an appearance I have repeatedly met with in bergs,

both out at sea and in the fiords. The height of the example under notice was

about 40 feet, its length being about 100 feet.

The shaded portion of fig. 1 shows the berg as seen above the water-level

A A,—one half of the original line of flotation a a being visible, the other half

being submerged. The dotted outline gives an ideal view of the portion below

water, the submerged half of the original line of flotation being shown, and the

base of the berg e f . Tig. 2 gives an ideal view of the same as it appeared before

the separation of the mass (i, B B being the bed of the fiord.

Fig. 1. Fig. 2.

---

There are evidently but two modes in which the horizontal line, a a, could have

been tilted up as seen in fig. I ; that is, either by the addition of a mass in the

direction of / , or by the separation of a mass in the direction of e. Either of

these causes might produce the result. In the case of floating pieces of ice, however,

the latter would be the more likely occurrence; and in the example under

notice, it was quite manifest, from the appearance of the surface, that a lai-ge mass

had recently been detached at d. Such a mass, although materially adding to

the cubical contents of the berg, would have the effect of distributing the weight

equally round the centre of gravity, and of sustaining the portion a t / a t a higher

level by acting as a counterpoise, as sho-wn in fig. 2. On the other hand, it is

evident that the separation of such a mass as d would at once throw the centre

of gravity further towards / and thus cause it to assume a deeper level, as in

fig. I.

Although these diagrams represent an imaginary case, in so far as the portion

below water is concerned, there cannot be a doubt of the fact which they are

intended to demonstrate, namely, that it is an error to assume that because a

mass of ice drifts along in a given depth of water without touching the bottom,

it may not, by such a process as has just been described, tilt over and immediately

ground. I t is obvious, therefore, that tlie mere circumstance of a fiord being