‘ Mightiest o f all the beasts o f chase

That roam in woody Caledon,

Crashing the forest in his race

The Mountain Bull comes thundering on.

Fierce, on the hunter's quiver’d band

He rolls his eyes o f swarthy glow,

Spurns with black hoof and horn the sand,

And tosses high his mane o f snow.’

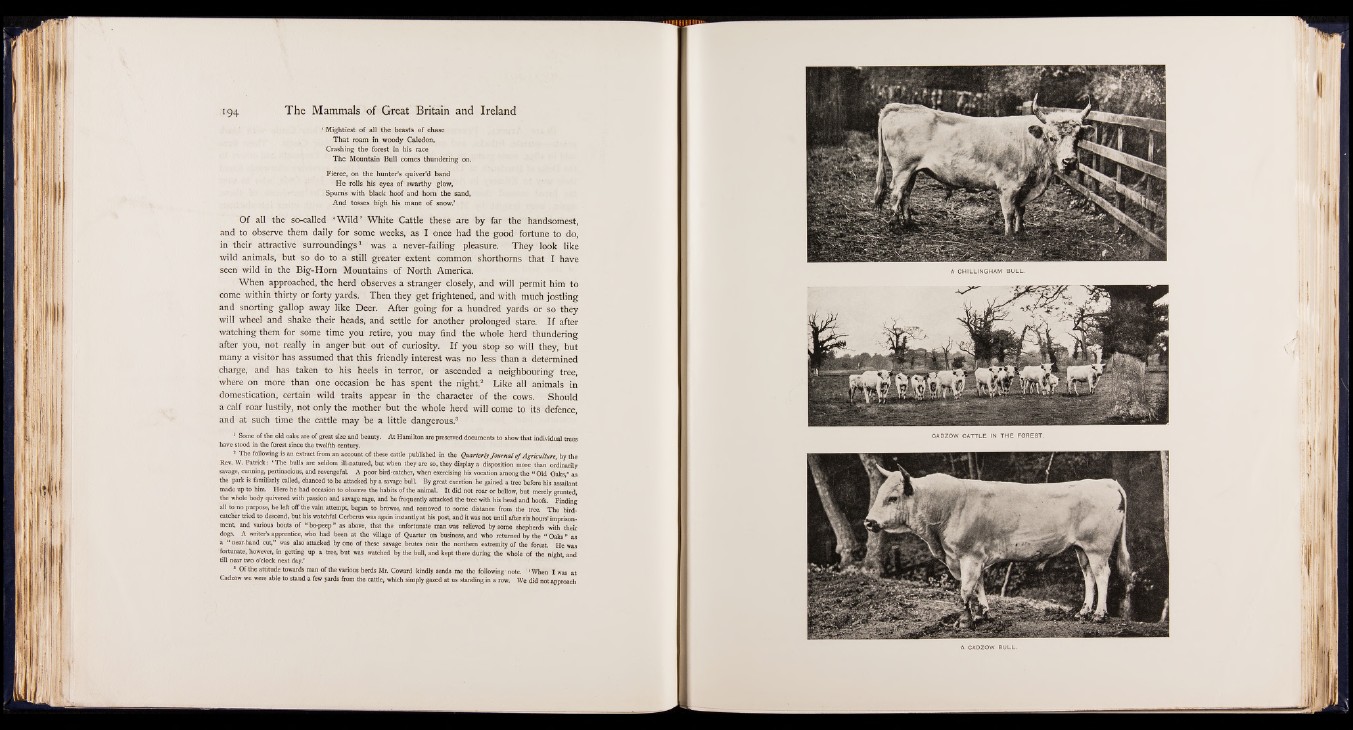

Of all the so-called ‘Wild ’ White Cattle these are by far the handsomest,

and to observe them daily for some weeks, as I once had the good fortune to do,

in their attractive surroundings1 was a never-failing pleasure. They look like

wild animals, but so do to a still greater extent common shorthorns that I have

seen wild in the Big-Horn Mountains of North America.

When approached, the herd observes a stranger closely, and will permit him to

come within thirty or forty yards. Then they get frightened, and with much jostling

and snorting gallop away like Deer. After going for a hundred yards or so they

will wheel and shake their heads, and settle for another prolonged stare. I f after

watching them for some time you retire, you may find the whole herd thundering

after you, not really in anger but out of curiosity. I f you stop so will they, but

many a visitor has assumed that this friendly interest was no less than a determined

charge, and has taken to his heels in terror, or ascended a neighbouring tree,

where on more than one occasion he has spent the night.2 Like all animals in

domestication, certain wild traits appear in the character of the cows. Should

a calf roar lustily, not only the mother but the whole herd will come to its defence

and at such time the cattle may be a little dangerous.8

1 Some of the old oaks are of great size and beauty. At Hamilton are preserved documents to show that individual trees

have stood in the forest since the twelfth century.

a The following is an extract from an account of these cattle published in the Quarterly Journal o f Agriculture, by the

Rev. W. Patrick: ‘The bulls are seldom ill-natured, but when they are so, they display a disposition more than ordinarily

savage, cunning, pertinacious, and revengeful A poor bird-catcher, when exercising his vocation among the “ Old Oaks ” as

the park is familiarly called, chanced to be attacked by a savage bull. By great exertion he gained a tree before his assailant

made up to him. Here he had occasion to observe the habits of the animal. It did not roar or bellow, but merely grunted,

the whole body quivered with passion and savage rage, and he frequently attacked the tree with his head and hoofs. Finding

all to no purpose, he left off the vain attempt, began to browse, and removed to some distance from the tree. The bird-

catcher tried to descend, but his watchful Cerberus was again instantly at his post, and it was not until after six hours’ imprisonment,

and various bouts of “ bo-peep ” as above, that the unfortunate man was relieved by some shepherds with their

dogs. A writer’s apprentice, who had been at the village of Quarter on business, and who returned by the “ Oaks ” as

a “ near-hand cut,” was also attacked by one of these savage brutes near the northern extremity of the forest. He was

fortunate, however, in getting up a tree, but was watched by the bull, and kept there during the whole of the night, and

till near two o’clock next day.’

* Of the attitude towards man of the various herds Mr. Coward kindly sends me the following note. 'When I was at

Cadzow we were able to stand a few yards from the cattle, which simply gazed at us standing in a row. We did not approach

A CADZOW BULL.