to bolt, and then dash away on tottering legs towards its mother, who is generally

circling around. The calf can gallop a considerable distance at full speed with the

mother, who will head it suddenly into some piece of fresh cover and force it to lie

again by pressing down its hind quarters with her chin. Even before the young

are dropped, hinds have an instinctive dread of dogs, and will boldly charge

any small canine that comes near them and strike it with their fore feet. A small

spaniel of mine was nearly killed by an infuriated hind whose calf I was photographing.

The hind knocked the dog over three times, and, had there not been a

fenced-in covert close by, the dog would doubtless have ended its career. As it

was, even when I picked it up and carried it away the angry hind followed me

closely, grinding her teeth with such rage that I thought she would try to strike

the dog as I held i t . ,

It has never been satisfactorily explained why in some seasons nearly all the

calves are males, and in another there is a preponderance of females. Yet this

is undoubtedly the case, as I have noticed when marking calves in Wamham Park;

it .is also true that more male calves die than those of the opposite sex. They

are like boys, more delicate.

Young Stags will breed with the hinds at eighteen months old, but grow

somewhat slowly after the third year. They are usually considered fit to shoot at

six or seven years, being then fulkgrown, but they do not reach their prime in a

wild state till eleven.1

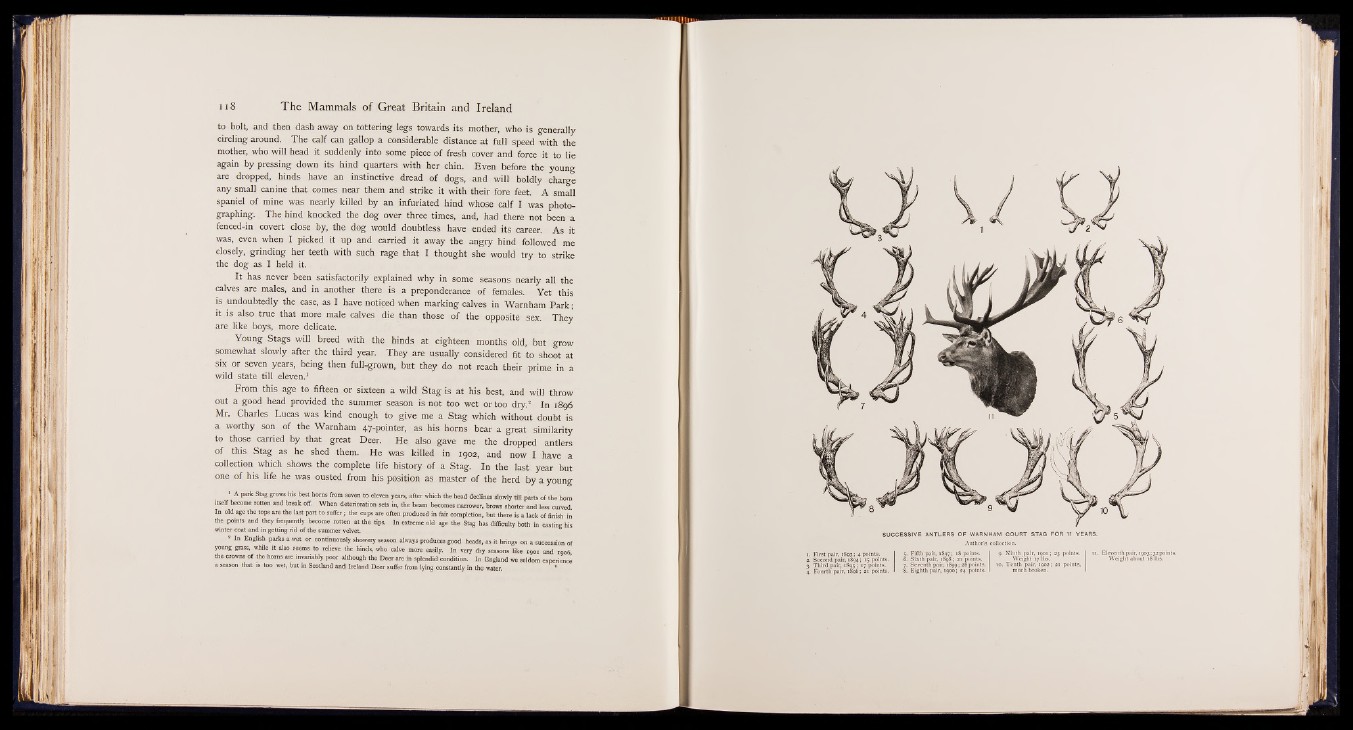

From this age to fifteen or sixteen a wild Stag is at his best, and will throw

out a good head provided the summer season is not too wet or too dry.2 In 1896

Mr. Charles Lucas was kind enough to give me a Stag which without doubt is

a worthy son of the Warnham 47-pointer, as his horns bear a great similarity

to those carried by that great Deer. He also gave me the dropped antlers

of this Stag as he shed them. He was killed in 1902, and now I have a

collection which shows the complete life history of a Stag. In the last year but

one of his life he was ousted from his position as master of the herd by a young

1 A park Stag grows his best horns from seven to eleven years, after which the head declines slowly till parts of the horn

itself become rotten and break off. When deterioration sets in, the beam becomes narrower, brows shorter and less curved.

In old age the tops are the last part to suffer; the cups are often produced in fair completion, but there is a lack of finish in

the points and they frequently become rotten at the tips. In extreme old age the Stag has difficulty both in casting his

winter coat and in getting rid of the summer velvet.

8 In English parks a wet or continuously showery season always produces good heads, as it brings on a succession of

young grass, while it also seems to relieve the hinds, who calve more easily. In very dry seasons like 1901 and 1906,

the crowns of the horns are invariably poor although the Deer are in splendid condition. In England we seldom experience

a season that is too wet, but in Scotland and Ireland Deer suffer from lying constantly in the water.