f i l l i

1 t

I

l i

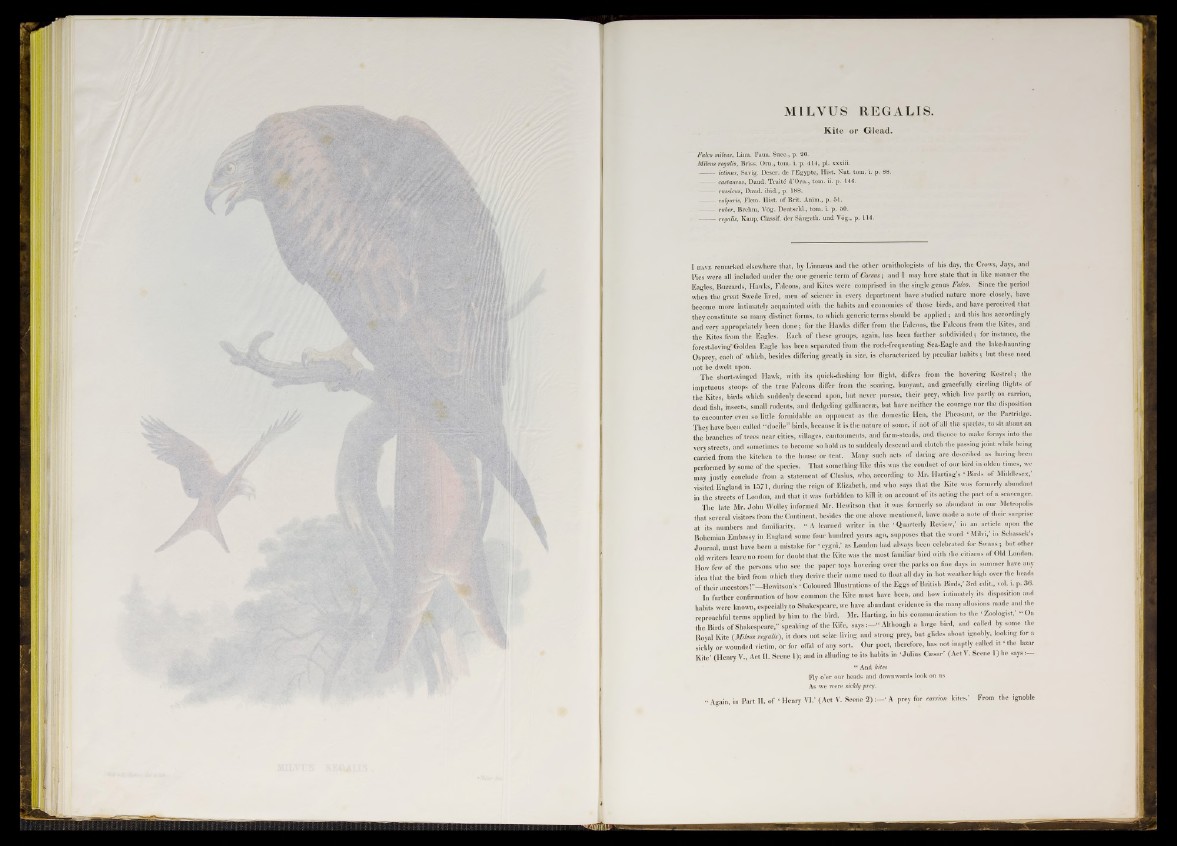

M1LVUS REGALIS.

Kite or Glead.

Falco mileiis, Liim. Faun. Suec., p. 20.

M ilv u s r e g a lia , Briss. Orn., tom. i. p. 41t, pi. xxxiii.

— ic lin u s , Savig. Descr. de l’Egypte, Hist. Nat. tom. i. p. 88.

— castaneus, Daud. Traité d’Om., tom. ii. p. 146.

— r u s s i c u s , Daud. Ibid., p. 188.

— v u lg a r is , Flem. Hist, of Brit. Anirn., p. 51.

— ru b e r , Brehm, Vog. Deutschl., tom. i. p. 50.

r e g a lis , Kaup, Classif. der Saugeth. und Vog., p. 114.

I h a v e remarked elsewhere that, hy Linnmus and the other ornithologists of his day, the Crows, Jays, and

Pies were all included under the one generic term of Corvus; and I may here state that in like manner the

Eagles, Buzzards, Hawks, Falcons, and Kites were comprised in the single genus Falco, Since the period

when the great Swede lived, men o f science in every department have studied nature more closely, have

become more intimately acquainted with the habits and economies o f those birds, and have perceived that

they constitute so many distinct forms, to which generic terms should be applied; and this has accordingly

and very appropriately been d o n e ; for the Hawks differ from the Falcons, the Falcons from the Kites, and

the Kites from the Eagles. Each o f these groups, again, has been further subdivided; for instance, the

forest-loving'Golden Eagle has been separated from the rock-freqiieutiug Sea-Eagle and the lake-haunting

Osprey, each of which, besides differing greatly in size, is characterized hy peculiar habits; but these need

not he dwelt upon.

The short-winged Hawk, with its quick-dashing low flight, differs from the hovering Kestrel; the

impetuous stoops of the true Falcons differ from the soaring, buoyant, and gracefully circling flights of

the Kites, birds which suddenly descend upon, hut never pursue, their prey, which live partly on carrion,

dead fish, insects, small rodents, and fledgeling gallinaceK, but have neither the courage nor the disposition

to encounter even so little formidable an opponent as the domestic Hen, the Pheasant, or the Partridge.

They have been called “ docile” birds, because it is the nature of some, if not of all the species, to sit about on

the branches of trees near cities, villages, cantonments, and farm-steads, and thence to make forays into the

very streets, and sometimes to become so hold as to suddeidy descend and clutch the passing joint whde being

carried from the kitchen to the house or tent. Many such acts of daring are described as having been

performed by some o f the species. That something like this was the conduct of our bird in oldeu times, we

may justly conclude from a statement o f Clusius, who, according to Mr. Hartiug's ‘ Birds of Middlesex,'

visited England in 1571, during the reign o f Elizabeth, and who says that the Kite was formerly abundant

in the streets of London, and that it was forbidden to kill it on account o f its acting the p art of a scavenger.

The late Mr. John Wolley informed Mr. Hewitson that it was formerly so abundant iu our Metropolis

that several visitors from the Continent, besides the one above mentioned, have made a note of their surprise

at its numbers and familiarity. “ A learned writer in the ’ Quarterly Review,' in an article upon the

Bohemian Embassy in England some four hundred years ago, supposes that the word ■ Milvi,’ in Schassek's

Journal, must have been a mistake for ‘ cygni,’ as London had always been celebrated for Swans ; but other

old writers leave no room for doubt that the Kite was the most familiar bird with the citizens of Old London.

How few o f the persons who see the paper toys hovering over the parks on fine days iu summer have any

idea that the bird from which they derive their name used to float all day in hot weather high over the heads

o f their ancestors!”—Hewitson's ‘ Coloured Illustrations of the Eggs o f British Birds,’ 3rd edit., vol. i. p. 30.

In further confirmation o f how common the Kite must have been, and how intimately its disposition anti

habits were known, especially to Shakespeare, we have abundant evidence in the many allusions made and the

reproachful terms applied hy him to the bird. Mr. Harting, in his communication to the ’ Zoologist,’ fl Ou

the Birds o f Shakespeare," speaking of the Kite, s a y s A l t h o u g h a large bird, and called by some the

Royal Kite (Milms regalis), it does not seize living and strong prey, but glides about ignobly, looking for a

sickly or wounded victim, o r for offal of any sort. Our poet, therefore, has not inaptly called it ‘ the lazar

Kite’ (Henry V., Act II. Scene I ); aud in alluding to its habits in • Julius Cffisar’ (Act V. Scene 1) he says

“ And kites

Fly o’er our heads and downwards look on us

As we were sickly prey.

Again, in Part II. of ' Henry VI.’ (Act V. Scene 2 ) ’ A prey for carrion kites.’ From the ignoble