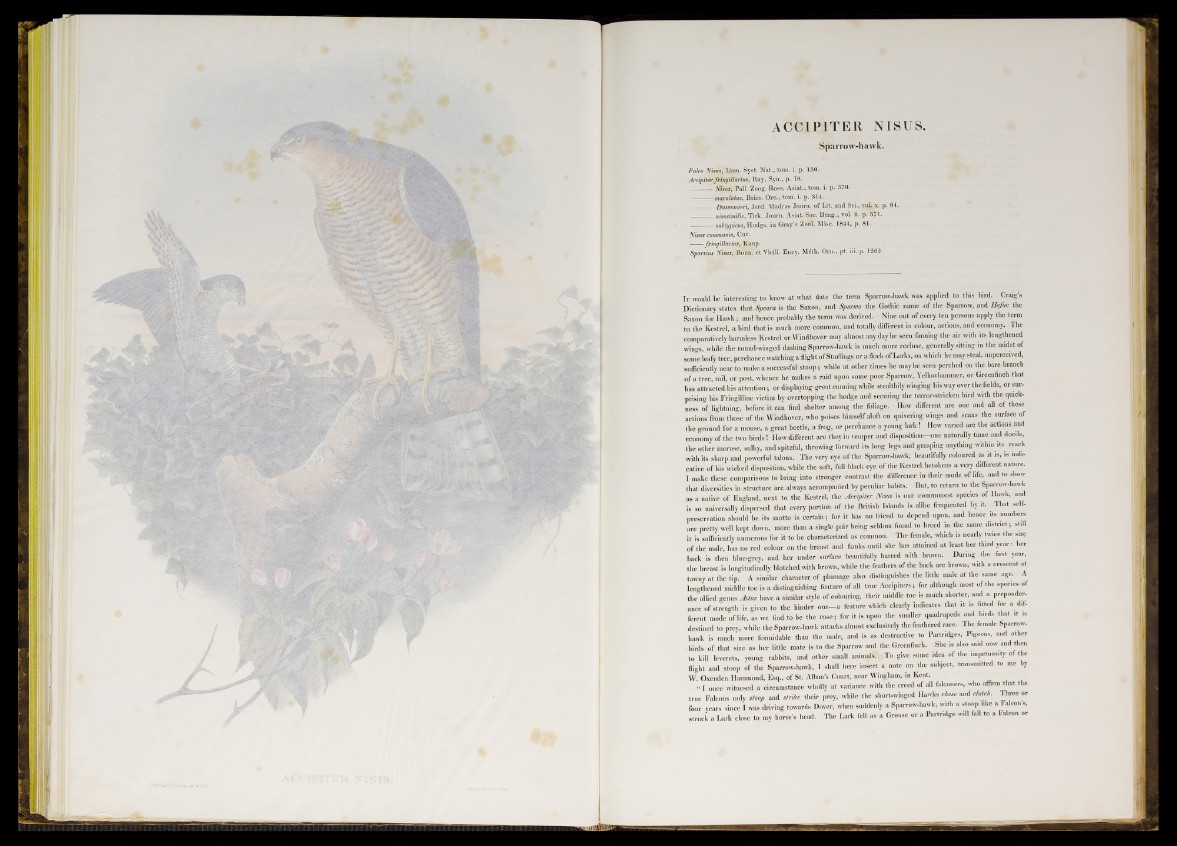

ACC1PITER NISUS .

Sparrow-hawk.

Falco Nisus, Lipn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 130.

Accipiter fringillarius, Ray, Syn., p. 18.

— Nisus, Pall. Zoog. Ross. Asiat., tom. i. p. 370.

----------maculatus, Briss. Orn., tom. i. p. 314.

— Dussumieri, Jerd. Madras Journ. of Lit. and Sei., vol. x. p. 84.

----------nisosimilis, Tick. Journ. Asiat. Sac. Beng., vol. ii. p. 571.

----------subtypicus, Hodgs. in Gray’s Zool. Misc. 1844, p. 81.

Nisus communis, Cuv.

. fringillarius, Kaup.

Sparvius Nisus, Bonn, et Vieill. Ency. M6th. Orn., pt. iii. p. 1262.

I t would be interesting to know at what date the term Sparrow-hawk was applied to this bird. Craig’s

Dictionary states th at Speara is the Saxon, and Sparma the Gothic name of the Sparrow, and Hafoc the

Saxon for Hawk ; and hence probably the term was derived. Nine out of every ten persons apply the term

to the Kestrel, a bird that is much more common, and totally different in colour, actions, and economy. The

comparatively harmless Kestrel or Windhover may almost any day be seen fanning the air with its lengthened

wings, while the round-winged dashing Sparrow-hawk is much more reclnse, generally sitting in the midst of

some leafy tree, perchance watching a flight of Starlings o r a flock o f Larks, on which he may steal, unperceived,

sufficiently near to make a successful sto o p ; while a t other times he may be seen perched on the bare branch

o f a tree, rail, o r post, whence he makes a raid upon some poor Sparrow, Yellowhammer, or Greenfinch that

has attracted his attention; or displaying great cunning while stealthily winging his way over the fields, or surprising

his Fringilline victim by overtopping the hedge and seenring the terror-stricken bird with the quickness

o f lightning, before it can find shelter among the foliage. How different are one and all o f these

actions from those o f the Windhover, who poises himself aloft on quivering wings and scans the surface of

the ground for a mouse, a great beetle, a frog, or perchance a young la rk ! How varied are the actions and

economy o f the two b ird s! How different are they in temper and disposition—one naturally tame and docile,

the other morose, sulky, and spitefiil, throwing forward its long legs and grasping anything within its reach

with its sharp and powerful talons. The very eye o f the Sparrow-hawk, beautifully coloured as it is, is indicative

of his wicked disposition, while the soft, full black eye of the Kestrel betokens a very different nature.

I make these comparisons to bring into stronger contrast the difference in their mode of life, and to show

that diversities in structure are always accompanied by peculiar habits. But, to return to the Sparrow-hawk

as a native of England, next to the Kestrel, the Accipiter Nisus is oor commonest species o f Hawk, and

is so universally dispersed that every portion o f the British Islands is alike frequented by it. That self-

preservation should be its motto is certain; for it has no friend to depend upon, and hence its numbers

arc pretty well kept down, more than a single pair being seldom found to breed in the same d istrict; still

it is sufficiently numerous for it to he characterized as common. The female, which is nearly twice the size

of the male, has no red colour on the breast and flanks until she has attained at least her third y e a r: her

back is then blue-grcy, and her under surface beautifully barred with brown. During the first year,

the breast is longitudinally blotched with brown, while the feathers o f the back are brown, with a crescent of

tawny at the tip. A similar character of plumage also distinguishes the little male at the same age. A

lengthened middle toe is a distinguishing feature of all true Accipiters; for although most of the species of

the allied genus Aslur have a similar style o f colouring, their middle toe is much shorter, and a preponderance

o f strength is given to the hinder one—a feature which clearly indicates that it is fitted for a different

mode o f life, as we find to be the case; for it is upon the smaller quadrupeds and birds th a t.it is

destined to prey, while the Sparrow-hawk attacks almost exclusively the feathered race. The female Sparrow-

hawk is much more formidable than the mule, and is as destructive to Partridges, Pigeons, and other

birds of that size as her little mate is to the Sparrow and the Greenfinch. She is also said now and then

to kill leverets, young rabbits, and other small animals. To give some idea of the impetuosity of the

flight and stoop of the Sparrow-hawk, I shall here insert a note on the subject, transmitted to me by

W. Oxenden Hammond, Esq., of St. Alban's Court, near Wingham, in Kent.

i I once witnesed a circumstance wholly a t variance with the creed of all falconers, who affirm that the

true Falcons only M and strike their prey, while the short-winged Hawks chase and dutch. Three or

four years since I was driving towards Dover, when suddenly a Sparrow-hawk, with a stoop like n Falcon s,

struck a Lark close to my horse's head. The Lark fell as a Grouse or a Partridge will fall to a Falcon or