• I Wolf kKCTtichUr. d/Jj tt/liûo.

MÏL VUS KE 6AIIS

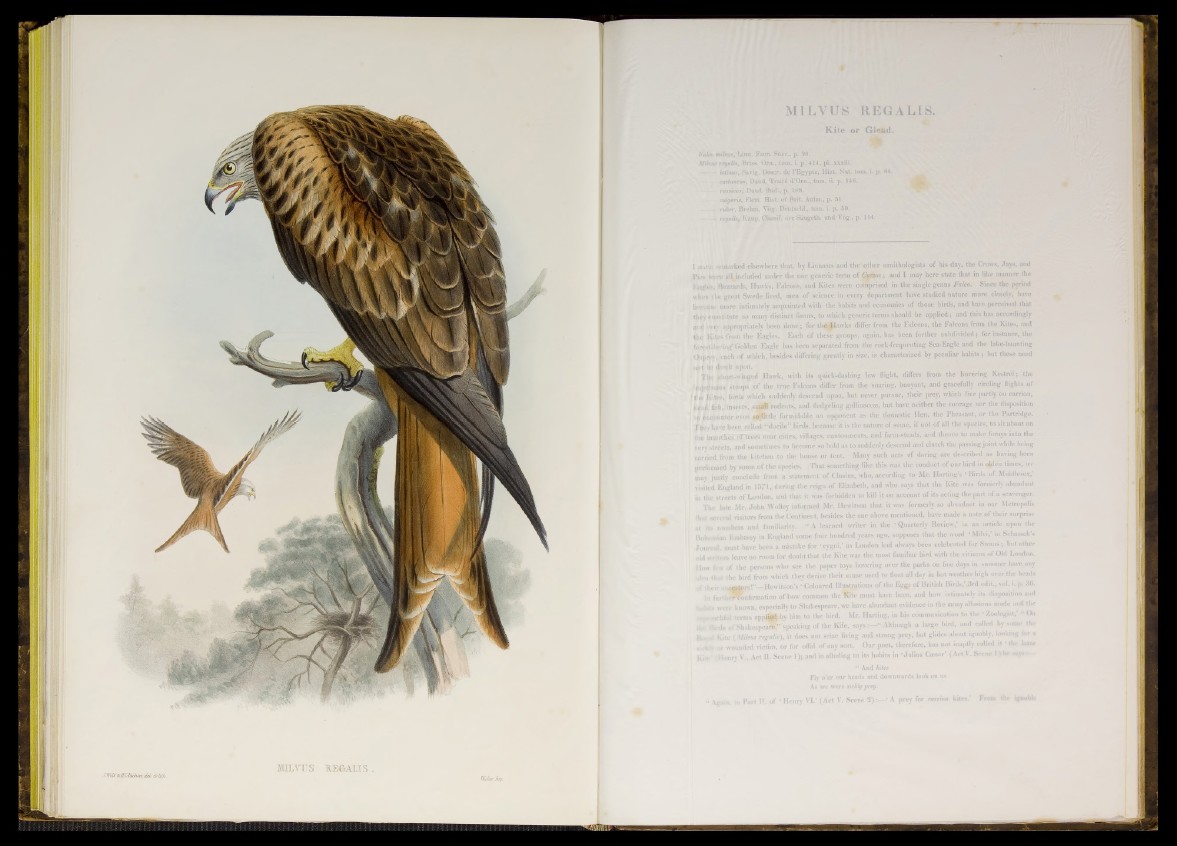

M1 L V U S REGAL I 8 .

Kite or Glead.

Falctt milvus, Linn. Faun. Suec., pi 20.

Mihus regaiis, Briss. Orn., tom. i. p. 414, pi. xxxiii.

ictinus, Savig. Descr. de l’Egypte, Hist. Nat. tom. i. p. 88.

- castaneus, Daud. Traité d’Orn., tom. ii. p. 146.

- russieusi Daud. ibid., p. 188.

- - vulgaris, Flem. Hist, of B rit Anim., p. 51.

- ruber, Brehm, Vbg. Deutschl., tom. i. p. 50.

- r e g a iis , Kaup, Classif. derSaugeth. und Vog., p. 114.

I iiavk e marked elsewhere that, by Linnaeus and the other ornithologists o f his day, the Crows, Jays, and

Pies w r e ail included under the one generic term o f Cg0us; and I may here state that in like manner the

Fade*, Buzzards, Hawks, Falcons, and Kites were comprised in the single genus Falco. Since the period

when the great Swede lived, men o f scieuce in every department have studied nature more closely, have

become more intimately acquainted with the habits and economies o f those birds, and have perceived that

they constitute so many distinct forms, to which generic terms should be applied ; and this has accordingly

and w rv appropriately been done; for the Hawks differ from the Falcons, the Falcons from the Kites, and

the Kites from the Eagles. Each of these groups, again, has been further subdivided; for instance, the

forest Joving Golden Eagle lias been separated from the rock-frequenting Sea-Eagle and the lake-haunting

O sp r e y , each of which, besides differing greatly in size, is characterized by peculiar habits; but these need

I** dwelt upon.

j IJ'I,,. idiort-mngcd Hank, with its quick-dashing low flight, differs from the hovering Kestrel; the

■htiteinons stoops o f the true Falcons differ from the soaring, buoyant, and gracefully circling flights of

f it Kites, birds which suddenly descend upon, but never pursue, their prey, which live partly on carrion,

t .e .i fi-lt, insects, sunfll rodents, and fledgeling gallinacete, but have neither the courage nor the disposition

t» fiieinmler even so little formidable an opponent as the domestic Hen, the Pheasant, or the Partridge.

They have been trailed "docile” birds, becaose it is the nature o f some, if not o f all the species, to sit about on

ttie branches o f trees near cities, villages, cantonments, and farm-steads, and thence to make forays into the

«err streets, and sometimes to become so hold as to suddenly descend and clutch the passing joint while being

carried from the kitchen to the house or tent. Many such acts of daring are described as having been

performed by some o f the species. That something like this was the conduct of our bird in olden times, we

may justly conclude from a statement o f Clusins, who, according to Mr. Harting’s ‘ Birds of. Middlesex,’

visited England in 1571, during the reign o f Elizabeth, and who says that the Kite was formerly abundant

in the streets of London, and that it was forbidden to kill it on account o f its acting the part of a scavenger.

The late Mr. John Woliey informed Mr. Hewitson that it was formerly so abundant in our Metropolis

that several visitors from the Continent, besides the one above mentioned, have made a note of their surprise

at it» numbers and familiarity. "A learned writer in the • Quarterly Review,’ in an artiele upon the

Bohemian Embassy in England some four hundred years ago, supposes that the word ■ Milvi,’ in Schassek’s

Journal, must have been a mistake for ■ cygni,’ as London had always been celebrated for Swans; hut other

„ « e r g leave no room for doubt that the Kite was the most familiar bird with the citizens of Old London.

How lew o f the persons who see the paper toys hovering over the parks on floe days in summer have any

nlea thm the bird from which they derive their name used to float all day in hot weather high over the heads

. their eestprs!” Hewitson’s ‘Coloured Illustrations o f the Eggs o f British Birds,’,3 rd edit., vol. i. p. 30.

in fur . nr confirmation of how common the Kite must have been, and how intimately its disposition and

teduls were known, especially to Shakespeare, we have abundant evidence in the many allusions made and the

, terms applied by him to the bird. Mr. Harting, in his communication to the ‘ Zoologist,' “ On

... ■ ,-tis in Shakespeare,” speaking o f the Kite, s a y s A l t h o u g h a large bird, and called by some the

Huvai Kite (Mi/tus regn/fr), it does not seize living and strong.prey, but glides about ignobly, looking for a

tieM» or wounded victim, or for offal of any sort. Our poet, therefore, has not inaptly called it ‘ the Inzer

Kite (Henry V., Act II. Scene 1); and in alluding to its habits in 'Ju liu s Csesar’ (Act V. Scene l ) b e mm» ;

“ And kites

Fly o’er onr heads and downwards look on us

As we were sickly prey.

■■ A earn, - i Part It. of ' Henry VI.’ (Act V. Scene 2 ) :—• A prey for rarrion kites.' From the ignoble