mm

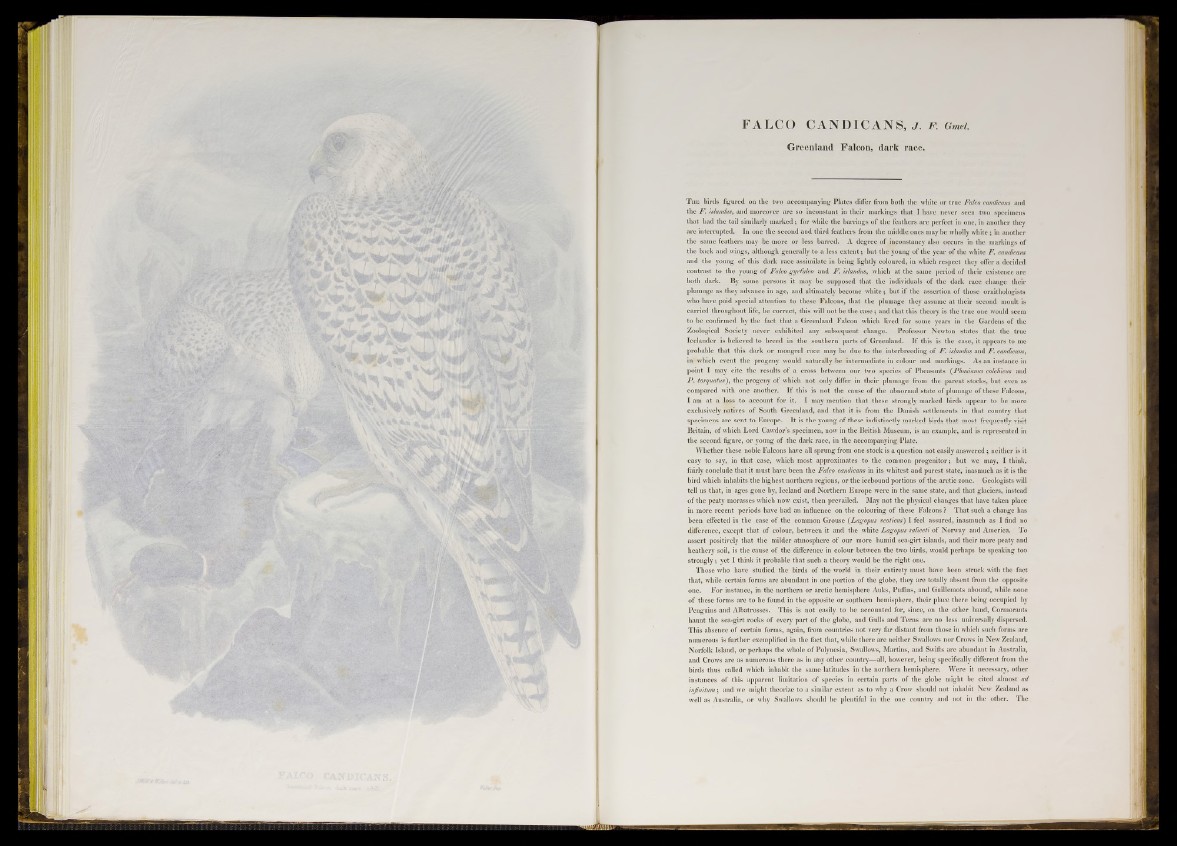

FALCO CANDICANS, j . f . Gmd.

Greenland Falcon, dark race.

T h e birds figured on the two accompanying Plates differ from both the white or true Falco candicans and

the F . islandus, and moreover are so inconstant in their markings that I have never seen two specimens

that had the tail similarly marked; for while the barrings o f the feathers are perfect iu one, in another they

are interrupted. In one the second and third feathers from the middle ones may be wholly w hite; in another

the same feathers may be more or less barred. A degree of inconstancy also occurs in the markings of

the back and wings, although generally to a less ex ten t; but the young o f the year of the white F. candicans

and the young of this dark race assimilate in being lightly coloured, in which respect they offer a decided

contrast to the young of Falco gyrfalco and F. islandus, which a t the same period of their existence are

both dark. By some persons it may be supposed that the individuals o f the dark race change their

plumage as they advance in age, and ultimately become white; but if the assertion of those ornithologists

who have paid special attention to these Falcons, that the plumage they assume at their second moult is

carried throughout life, be correct, this will not be the c ase; and that this theory is the true one would seem

to be confirmed by the fact that a Greenland Falcon which lived for some years in the Gardens of the

Zoological Society never exhibited any subsequent change. Professor Newton states that the true

Icelander is believed to breed in the southern parts o f Greenland. If this is the case, it appears to me

probable that this dark o r mongrel race may be due to the interbreeding o f F . islandus and F. candicans,

in which event the progeny would naturally be intermediate iu colour and markings. As an instance in

point I may cite the results o f a cross between our two species of Pheasants (Phasiams colchicus and

P . torquatus), the progeny of which not only differ in their plumage from the parent stocks, but even as

compared with one another. I f this is not the cause of the abnormal state o f plumage o f these Falcons,

I am a t a loss to account for it. I may mention that these strongly marked birds appear to be more

exclusively natives o f South Greenland, and that it is from the Danish settlements in that country that

specimens are sent to Europe. I t is the young of these indistinctly marked birds that most frequently visit

Britain, o f which Lord Cawdor’s specimen, now in the British Museum, is an example, and is represented in

the second figure, or young of the dark race, in the accompanying Plate.

Whether these noble Falcons have all sprung from one stock is a question not easily answered; neither is it

easy to say, in that case, which most approximates to the common progenitor; but we may, I think,

fairly conclude that it must have been the Falco candicans in its whitest and purest state, inasmuch as it is the

bird which inhabits the highest northern regions, or the icebound portions of the arctic zone. Geologists will

tell us that, in ages gone by, Iceland and Northern Europe were in the same state, and that glaciers, instead

o f the peaty morasses which now exist, then prevailed. May not the physical changes that have taken place

in more recent periods have had an influence on the colouring o f these Falcons ? That such a change has

been effected in the case o f the common Grouse (Lagopus scolicus) I feel assured, inasmuch as I find no

difference, except that o f colour, between it and the white Lagopus saliceti of Norway and America. To

assert positively that the milder atmosphere o f our more humid sea-girt islands, and their more peaty and

heathery soil, is the cause of the difference in colour between the two birds, would perhaps be speaking too

strongly; yet I think it probable that such a theory would be the right one.

Those who have studied the birds o f the world in their entirety must have been struck with the fact

that, while certain forms are abundant in one portion of the globe, they are totally absent from the opposite

one. F o r instance, in the northern or arctic hemisphere Auks, Puffins, and Guillemots abound, while none

o f these forms are to be found in the opposite or sopthern hemisphere, their place there being occupied by

Penguins and Albatrosses. This is not easily to be accounted for, since, on the other hand, Cormorants

haunt the sea-girt rocks o f every part o f the globe, and Gulls and Terns are no less universally dispersed.

This absence o f certain forms, again, from countries not very far distant from those in which such forms are

numerous is further exemplified in the fact that, while there are neither Swallows nor Crows in New Zealand,

Norfolk Island, o r perhaps the whole o f Polynesia, Swallows, Martins, and Swifts are abundant in Australia,

and Crows are as numerous there as in any o ther country—all, however, being specifically different from the

birds thus called which inhabit the same latitudes in the northern hemisphere. Were it necessary, other

instances of this apparent limitation o f species in certain parts of the globe might be cited almost ad

injinitum; and we might theorize to a similar extent as to why a Crow should not inhabit New Zealand as

well as Australia, or why Swallows should be plentiful in the one country and not in the other. The