Hi S C

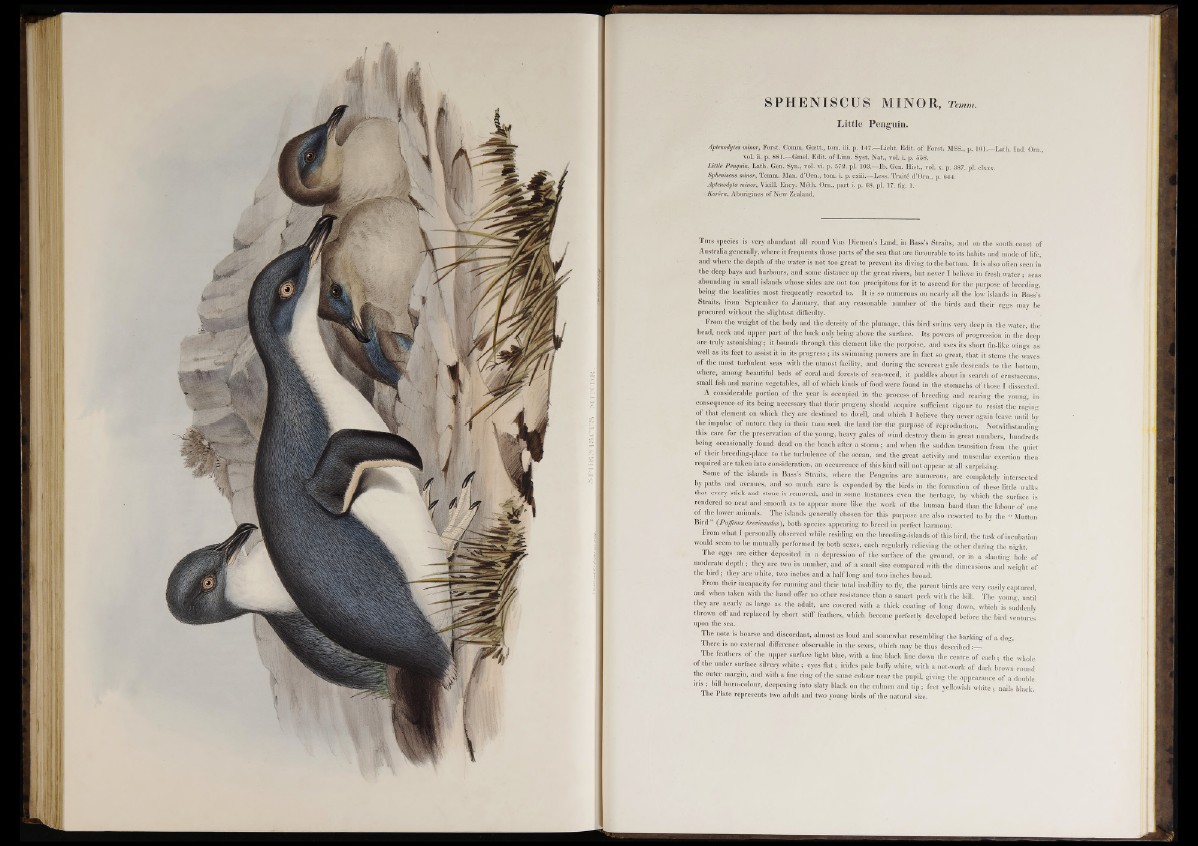

SPHENISCUS MINOR, Temm.

Little Penguin.

Aptenodytes minor, Forst. Comm. Goett., tom. iii. p. 147.— Licht. Edit, o f Forst. MSS., p. 101.— Lath. Ind. Ora.,

vol. ii. p. 881.—Gmel. Edit, of Linn. Syst. Na t., vol. i. p. 558.

Little Penguin, Lath. Gen. Syn., vol. vi. p. 572. pi. 103.— lb . Gen. Hist., vol. x. p. 387. pi. clxxx.

Spheniscus minor, Temm. Man. d’Orn., tom. i. p. cxiii.— Less. Traité d’Om., p. 644.

Aptenodyta minor, Yieill. Ëncy. Méth. Orn., p a r t i. p. 68. pi. 17. fig. l.

Korôra, Aborigines of New Zealand.

T h is species is very abundant all round Van Diemen’s Land, in Bass’s Straits, and on the south coast of

Australia generally, where it frequents those parts o f the sea that are favourable to its habits and mode of life,

and where the depth of the water is not too great to prevent its diving to the bottom. It is also often seen in

the deep bays and harbours, and some distance up the great rivers, but never I believe in fresh water; seas

abounding in small islands whose sides are not too precipitous for it to ascend for the purpose of breeding,

being the localities most frequently resorted to. It is so numerous on nearly all the low islands in Bass’s

Straits, from September to January, that any reasonable number of the birds and their eggs may be

procured without the slightest difficulty.

From the weight of the body and the density of the plumage, this bird swims very deep in the water, the

head, neck and upper part of the back only being above the surface. Its powers o f progression in the deep

are truly astonishing; it bounds through this element like the porpoise, and uses its short fin-like wings as

well as its. feet to assist it in its progress ; its swimming powers are in fact so great, that it steins the waves

o f the most turbulent seas with the utmost facility, and during the severest gale descends to the bottom,

where, among beautiful beds of coral and forests o f sea-weed, it paddles about in search of crustaceans!

; small fish and marine vegetables, all of which kinds of food were found in the stomachs of those I dissected.

A considerable portion o f the year is occupied in the process o f breeding and rearing the young, in

consequence o f its being necessary that their progeny should acquire sufficient vigour to resist the raging

Of that element on which they are destined to dwell, and which I believe they never again leave until by

the impulse of nature they in their turn seek the land for the purpose of reproduction. Notwithstanding

this care for the preservation of the young, heavy gales of wind destroy them in great numbers, hundreds

being occasionally found dead on the beach after a storm ; and when the sudden transition from the quiet

o f their breeding-place to the turbulence o f the ocean, and the great activity and muscular exertion then

required are taken into consideration, an occurrence o f this kind will not appear at all surprising.

Some of the islands in Bass’s Straits, where the Penguins are numerous, are completely intersected

by paths and avenues, and so much care is expended by the birds in the formation of these little walks

that every stick and stone is removed, and in some instances even 'ihe herbage, by which the surface is

rendered so neat and smooth as to appear more like the work o f the human hand than the labour o f one

of the lower animals. The islands generally chosen for this purpose are also resorted to by the “ Mutton

Bird ” (Puffinus trmamdui), both species appearing to breed in perfect harmony.

From what I personally observed while residing on the breeding-islands o f this bird, the task of incubation

would seem to he mutually performed by both sexes, each regularly relieving the other during the night.

The eggs are either deposited in a depression of the surface of the ground, or in a slanting hole of

moderate depth; they are two in number, and of a small size compared with the dimensions and weight of

the bird; they are white, two inches and a half long and two inches broad.

From their incapacity for running and their total inability to fly, the parent birds are very easily captured,

and when taken with the hand offer no; other resistance than a smart peck with the bill. The young, until

they are nearly as large as the adult, are covered with a thick coating of long down, which is suddenly

thrown off and replaced by short stiff feathers, which become perfectly developed before the bird ventures

upon the sea.

The note is hoarse and discordant, almost as loud and somewhat resembling the barking o f a dog.

There is no external difference observable in the sexes, which may be thus described

The feathers of the upper surface light blue, with a fine black line down the centre o f each ; the whole

of the under surface silvery white; eyes flat; irides pale buffy white, with a net-work of dark brown round

the outer margin, and with a fine ring of the same colour near the pupil, giving the appearance o f a double

iris ; bill horn-colour, deepening into slaty black on the culmen and tip ; feet yellowish white ; nails black.

The Plate represents two adult and two young birds of the natural size.