PUFFINUS BREVICAUDUS , —

Short-tailed Petrel.

Pujjmus brevicaudus, B randt, MSS.—L ist o f B irds in Brit; Mus. Coll., p a rt iii. p. 189.— Gould in Ann. and Mag.

o f Nat. Hist., vol. xiii. p. 365.

T h i s b i r d is an inhabitant of all the Australian seas, particularly those surrounding Van Diemen’s Land and

the islands in Bass’s Straits, to some o f which, but especially to Green Island, it resorts during the summer

in countless numbers for the purpose of breeding and rearing its young; thither also resort the sealers,

the natives, and even the settlers, in order to procure the eggs and young birds, which are salted and extensively

used as au article of food; the feathers are also collected for the purposes o f commerce. I visited

this island in January 1839, when, although the season was far-advanced, both eggs and young were still so

numerous as to excite feelings of astonishment. I had previously heard much of this great nursery of

Petrels, and might lengthen this paper by my own observations ; but as I find that an excellent account of

the bird and its habits has been published by Mr. Davies, in the second volume of the ‘Tasmanian Journal,’

I prefer transcribing his words

“ About the commencement of September these birds congregate in immense flocks, and shortly afterwards

proceed at sunset to the different isles upon which they have established their rookeries. Here they

remain during the night for the space of about ten days, forming their burrows and preparing for the

ensuing laying-season. They then leave, and continue at sea for about five weeks.

“ About the 20th of November at sunset a few come in to lay, and gradually increase in numbers until

the night o f the 24th. Still there are comparatively few, and a person would find some difficulty in collecting

two dozen eggs on the morning of that day.

“ It is not in my power to describe the scene that presents itself at Green Island on the night of the

24th o f November. A few minutes before sunset flocks are seen making for the island from every quarter,

and that with a rapidity hardly conceivable; when they congregate together, so dense is the cloud, that

night is ushered in full ten minutes before the usual time. The birds continue flitting about the island for

nearly an hour and then settle upon it. The whole island is burrowed; and when I state that there are not

sufficient burrows for one-fourth of the birds to lay in, the scene of noise and confusion that ensues may be

imagined—I will not attempt to describe it. On the morning of the 25th the male birds take their

departure, returning again in the evening, and so they continue to do until the end of the season . . . . Every

burrow on the island contains, according to its size, from one to three or four birds, and as many eg g s;

one is the general rule. At least three-fourtlis of the birds lay under the bushes, and the eggs are so

numerous, that great care must be taken to avoid treading upon them. The natives from Flinders generally

live for some days on Green Island at this time of the year for the purpose of collecting the eggs, and again

in March or April for curing the young birds . . . . Besides Green Island, the principal rookeries o f these

birds are situated between Flinders’ Island and Cape Barren, and most of the smaller islands in Furneaux’s

group. The eggs and cured birds form a great portion of the food o f sealers, and, together with the

feathers, constitute the principal articles o f their traffic. The mode by which the feathers are obtained

has been described to me as follows

“ The birds cannot rise from the ground, but must first go into the water; in effecting which, they make

numerous tracks to the beach similar to those of a kangaroo; these are stopped before morning, with the

exception o f one leading over a shelving bank, at the bottom of which is dug a pit in the sand ; the birds,

finding all avenues closed but this, follow each other in such numbers, that, as they fall into the pit, they are

immediately smothered by those succeeding them. It takes the feathers o f forty birds to weigh a pound ;

consequently sixteen hundred must be sacrificed to make a feather-bed of forty pounds weight. Notwithstanding

the enormous annual destruction of these birds, I did not, during the five years that I was in

the habit o f visiting the Straits, perceive any sensible diminution in their number. The young birds leave

the rookeries about the latter end of April, and form one scattered flock in Bass’s Straits. I have actually

sailed through them from Flinders’ Island to the heads of the Tamar, a distance of eighty miles. They

shortly afterwards separate into dense flocks, and finally leave the coast. The old birds are very oily, but

the young are literally one mass of fat, which has a tallowy appearance, and hence I presume the name of

Mutton Bird.” To this I may add that the young birds are very good when fresh, and the old birds after

being skinned and preserved in lime are excellent eating.

The egg is very large for the size of the bird, being two inches and three-quarters long by one inch and

seven-eighths broad, and is of a snow-white. The white or albumen forms a very large proportion of its

contents; and it is remarkable that a small part of both the yolk and the white remains soft and watery,

however long the egg may be boiled.

The food of the old birds consists o f shrimps, small crustaceans and mollusks, which they principally

procure from among the large beds of kelp along the coast. The young are fed with grass, sea-weed, &c.

The flight of this and the other species of Puffinus differs considerably from that of the Procellarice in

being straighter and performed close above the surface of the water; it is moreover so exceedingly rapid,

that Mr. Davies states it cannot be fairly estimated at less than sixty miles an hour.

The sexes are so much alike that they can only be distinguished by dissection.

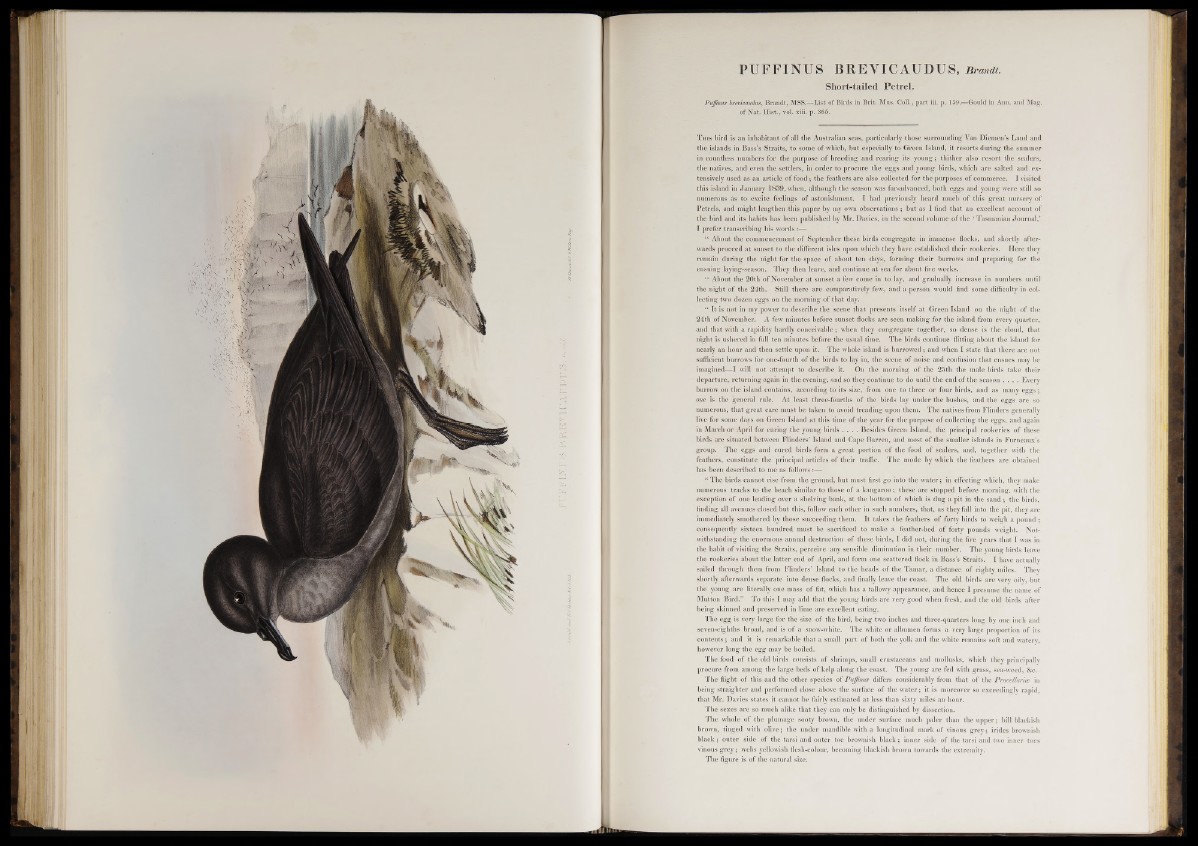

The whole of the plumage sooty brown, the under surface much paler than the upper; bill blackish

brown, tinged with olive; the under mandible with a longitudinal mark of vinous grey; irides brownish

black; outer side of the tarsi and outer toe brownish black; inner side of the tarsi and two inner toes

vinous grey; webs yellowish flesh-colour, becoming blackish brown towards the extremity.

The figure is of the natural size.