E EM E a tó íBM S

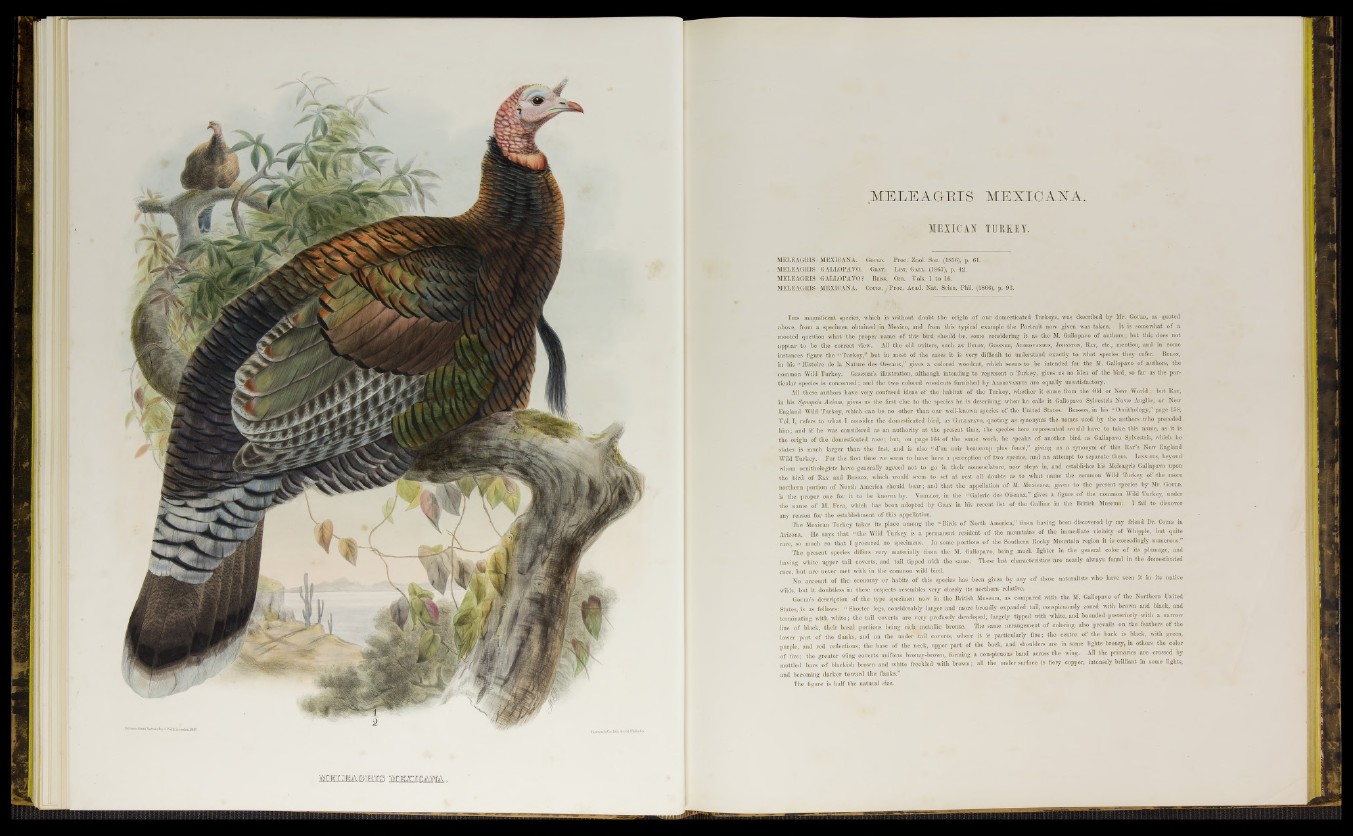

MELEAGRIS MEXICANA.

MEXICAN T U R K E Y .

MELEAGRIS - MEXIOANA. Goo»». Proc. Zool. So©.. (185% p. Cl. '**:•

MELEAGRIS GALLOPAYO. G ra y , L ist. G a l l . (1867), p. 42.

MBLBAGRIS GALLOPAYO? Brass1, Ora. Vols. 1 to 16.

MBLBAGRIS MEXIOANA. C o d e s./Proc. Acad. Nat. Scien. Phil. (1866), p. 93.

This magnificent species, which is without doubt the origin of our domesticated Turkeys, was described by Mr. Gould, as quoted

above, from a specimen obtained^in Mexico, and from this typical example the Portrait now given was taken. It is somewhat of a

mooted question what the proper .name of this bird should be, some considering it as the M. Gallopavo of authors; but this does not

appear to bo the correct view. All the old writers, such as Belon, Gessner, Aldrovandus, Jo h n sto n , Ray, etc., mention, and in some

instances figure the “ Turkey/.but in most o f the cases it is very difficult to understand exactly to what species they refer. Belon,

ini his “ Histo'ire de la Nature des Oiseaux,” gives a colored woodcut, which seems to be intended for the M. Gallopavo of authors, the

common Wild Turkey. Gessner’s illustration, although intending to represent a Turkey, gives us no idea of the bird, so far as the particular

species is concerned ; and the two colored woodcuts furnished by Ald ro v an d u s are equally unsatisfactory.

All these authors have very confused ideas of the habitat of the Turkey, whether it came from the Old or New World; but Ray,

in his ¡Synopsis Avium, gives us the first clue to the species he is describing when he calls it Gallopavo Sylvestris Nova Angli», or New

England Wild Turkey, which can bo no other than our well-known species of the United States. Brisson, in his “ Ornithology,” page 158,

' Yol. I , refers to what I consider the domesticated bird, as G allap a v o , quoting as synonyms the names used by the authors who preceded

him;, and if he was considered as ah authority at the present time, the species here represented would have to take this name, as it is

the origin o f the domesticated race; but, on page 164 of the same work, he speaks of another bird as Gallapavo Sylvestris, which he

states is much larger than the first, and is also “ d’un noir beauconp plus foncé,” giving as a synonym of this Ray’s New England

Wild Turkey. For the first time we seem to have here a perception of two species, and an attempt to separate them. Linnjsus, beyond

whom ornithologists have generally agreed not to go in their nomenclature, now steps in, and establishes his Melcagris Gallapavo upon

the bird of R ay and Brisson, which would seem to set at rest all doubts as to what name the common Wild Turkey of the more

northern portion o f North America should bear; and that the appellation o f M. Mexicana, given to the present species by Mr. Gould,

is the proper one for it to be known by. Yieillot, in the “ Galerie des Oiseaux,” gives a figure o f the common Wild Turkey, under

the name of M. Fera, which has been adopted by G ra y in his recent list of the Gallinm in the British Museum. I fail to discover

any reason for the establishment of this appellation.

The Mexican Turkey takes its place among the “ Birds of North America,” from having been discovered by my friend Dr. Codes in

Arizona. He says that “ the Wild Turkey is a permanent resident of the mountains of the immediate vicinity o f Whipple, but quite

rare, so much so that I procured no specimens. In some portions of the Southern Rocky Mountain region it is* exceedingly numerous.”

The present species differs very materially from the M. Gallopavo, being much lighter in the general color o f its plumage, and

having white upper tail coverts, and tail tipped with the same. These last characteristics are nearly always found in the domesticated

race, but are never met with in the common wild bird.

No account of tho economy or habits of this species has been given by any of those naturalists who have seen it in its native

wilds, but it doubtless in these respects resembles very closely its northern relative.

Gould’s description of the type specimen now in the British Museum, as compared with the M. Gallopavo o f the Northern United

States, is as follows: “Shorter legs, considerably larger and more broadly expanded tail, conspicuously zoned with brown and black, and

terminating with white; the tail coverts are very profusely developed, largely tipped with white, and bounded posteriorly with a narrow

line of black, their basal portions being rich metallic bronze. The same arrangement of coloring also prevails on the feathers of the

lower part of the flanks, and on the under tail coverts, where it is particularly fine; the centre of the back is black, with green,

purple, aud red reflections; the base of the neck, upper, part of the back, and shoulders are in some lights bronzy, in others the color

of fire; the greater wing coverts uniform bronzy-brown, forming a conspicuous band across the wing. All the primaries are crossed by

mottled bara o f blackish brown and white freckled with brown ; all the under surface is fiery copper, intensely brilliant in some lights,

and becoming darker toward the flanks.”

The figure is half the natural size.