lii:

iw

ever through the hard. Fourthly, that, at nearly four hundred paces from the loss of the

Móne, the water runs tolerably tranquil over a hard calcareous stratum, which it has not

worn through, but that, in consequence of the discontinuance of that stratum, the river,

with tremendous noise, has there formed a kind of subterraneous cataract. And fifthly,

that the channel in which the Rhône afterward runs through, which is still five and

thirty feet lower, having probably a very trifling declivity, the current naturally retains

after the fall nearly the same placid state, although much confined between its irregular

and chamfreted sides, until, again meeting with other calcareous strata which have

remained perfect, that is, without being worn through, the river has been forced to

make its way under them, thereby disappearing for the space of three hundred and fifty

feet, which is the length of the vault or irregular cavity in which it loses itself.

The first time I visited this remarkable spot, which is as curious as it is romantic, I

expected that a river, which, previous to its disappearance, is in itself so considerable,

and in many places rapid and impetuous, woul d re-appear with some degree of velocity;

but, on the contrary, I could scarcely discern the direction of its course j for, except

some trifling bubbles and eddies (occasioned no doubt by the confined particles of air

which disengage themselves from the water, and the resistance it experiences among the

craggy rocks in the interior of the mountain), it ascends, from its subterraneous channel,

with a most surprising placidness, unaccountable, unless upon the following principle :—

I t may, I presume, be attributed to the form of the channel, which is most probably

that of a siphon, with the leg or end, where the Rhone re-appears, more vertical than

the other;—a conjecture which seems the more probable, as it in a great measure accounts

for the total loss of a variety of objects, such as dogs, pigs, large pieces of timber, &c.

which have at different times been thrown in, by way of experiment. But, what is

more singular, this stagnant and almost motionless current re-assumes, at a short distance

from where it emerges from the subterraneous passage, the whole of its original

rapidity, and, by again becoming considerable, continues navigable until it reaches the

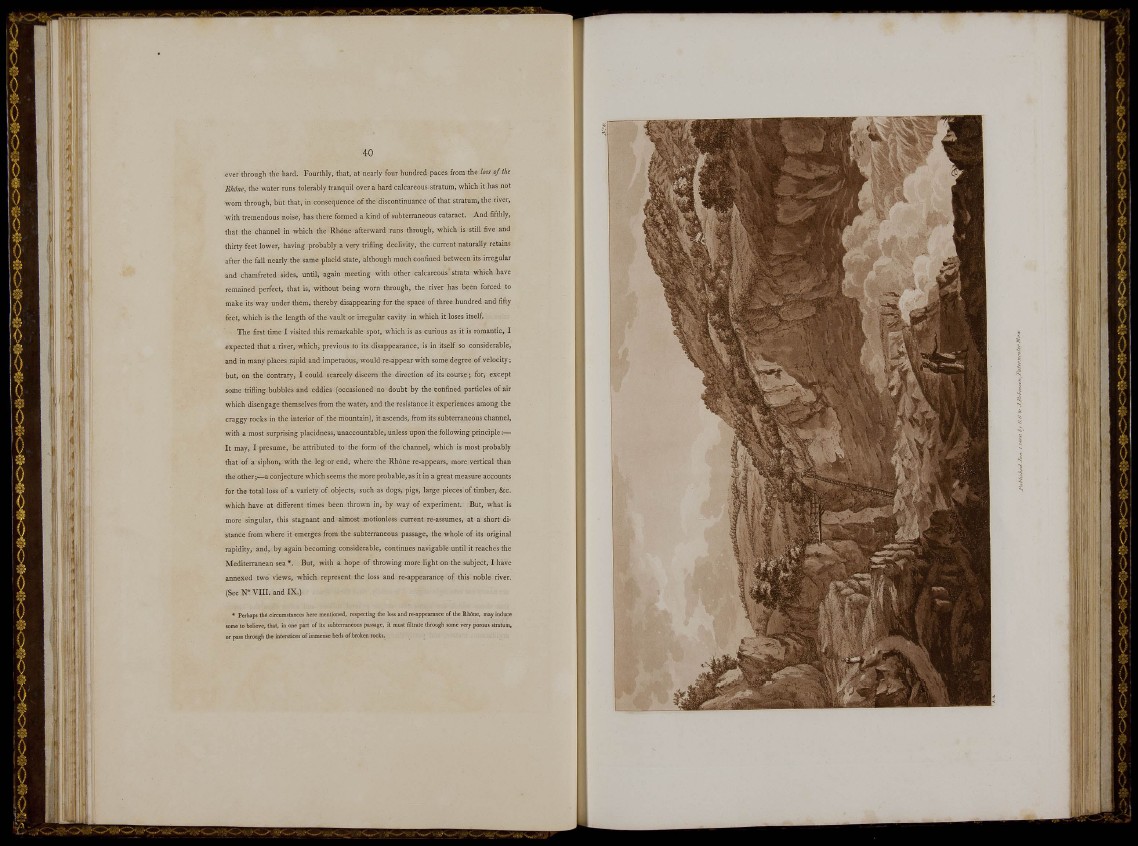

Mediterranean sea*. But, with a hope of throwing more light on the subject, I have

annexed two views, which represent the loss and re-appearance of this noble ri'

(See N" VI I I . and IX.)

• Perhaps thé circumstances here mentioned, respecting the loss and re-appcarance of the RhOnc, may induce

some to believe, that, in one part of its subterraneous passage, it must filtrate through some very porous stratum,

or pass through the intersUces of immense be<ls of broken rocks.