compressed or inflated; linear or variously contracted between the seed; continuous or jointed;

dehiscent or indehiscent; membranous or woody; 'longitudinally one or 2-celled', or divided by

transverse partitions, transversely many-celled ; with or without enclosed pulp surrounding the

seed. The seed like all other parts exhibit the same want of uniformity, they are either naked

or imbedded in pulp, or sometimes furnished with an arillus or large carunculus ; the embryo is

either straight or curved along the edge of the cotyledons;' the cotyledons are either thin and

foliaceous or thick and fleshy, usually without, but occasionally furnished with a copious albumen

as in Fillcea, and the section Cathartocarpus of Cassia. The only points on which they seem

all to agree is in having the odd segments of the calyx anterior or remote from the axis. This

is the only mark by which this order can always be distinguished from Rosacece, the fruit even,

not being always leguminous, in one genus, D e ta rium , it is drupaceous.

If from Botanical, or structural peculiarities, we turn to properties we find similar variations.

Among the arboreous forms the wood in some is of hardest and most durable description,

witness some of the Dalb erg ia s and Acacias, in others the very reverse is the case, as in

E r y th r in a and A g a ti. Nearly the whole of the tribe Papilionacece afford edible nutritious

grains, (beans, pease, in one word, pulse of all kinds) while the Cassias or Ccesalpineas are distinguished

by the possession of both purgative and astringent properties, the leaves of Senna for

example and the pulp which surrounds the seed of Cassia fi s tu la being powerful purgatives,

while the bark of C. auriculata is in constant use for tanning. Some of the Mimosas yield by

boiling a powerfully astringent extract (catchu). while others, abound in the purest of gum,'

endowed with simply emolient or mucilaginous properties: gum arabic, gum tragacanth,

and gum kino, though differing so widely from each other in their properties are all the produce

of this order. From a species of A lh a g i a kind of Manna is procured, while the leaves of

A g a t i g ra n d ifio ra , are bitter and tonic.

Such are a few of the anomalies and contradictions presented by this order, enough I

presume to show the difficulty or rather impossibility^ of defining satisfactorily so polymorphous

a tribe, and the necessity that exists, towards attaining a clear understanding of the

whole, that its parts be considered in succession as if each formed a distinct order. This is

the method followed by Bartling, who, adopting the divisions first marked out by Brown and

extended by DeCandolle, has merely departed from their arrangement, in raising the suborders

of these eminent Botanists to the rank of orders, perhaps an unnecessary innovation, but

one which I intend partially to follow here, as enabling me to give a clearer exposition

of the whole, and in less space, than if I attempted it in the mass. Before however pro^

ceeding to characterize in detail the suborders referable to the Indian flora I shall extract from

De Candolle’s Prodromus, a table, (see below) presenting at one view, a clear and comprehen-

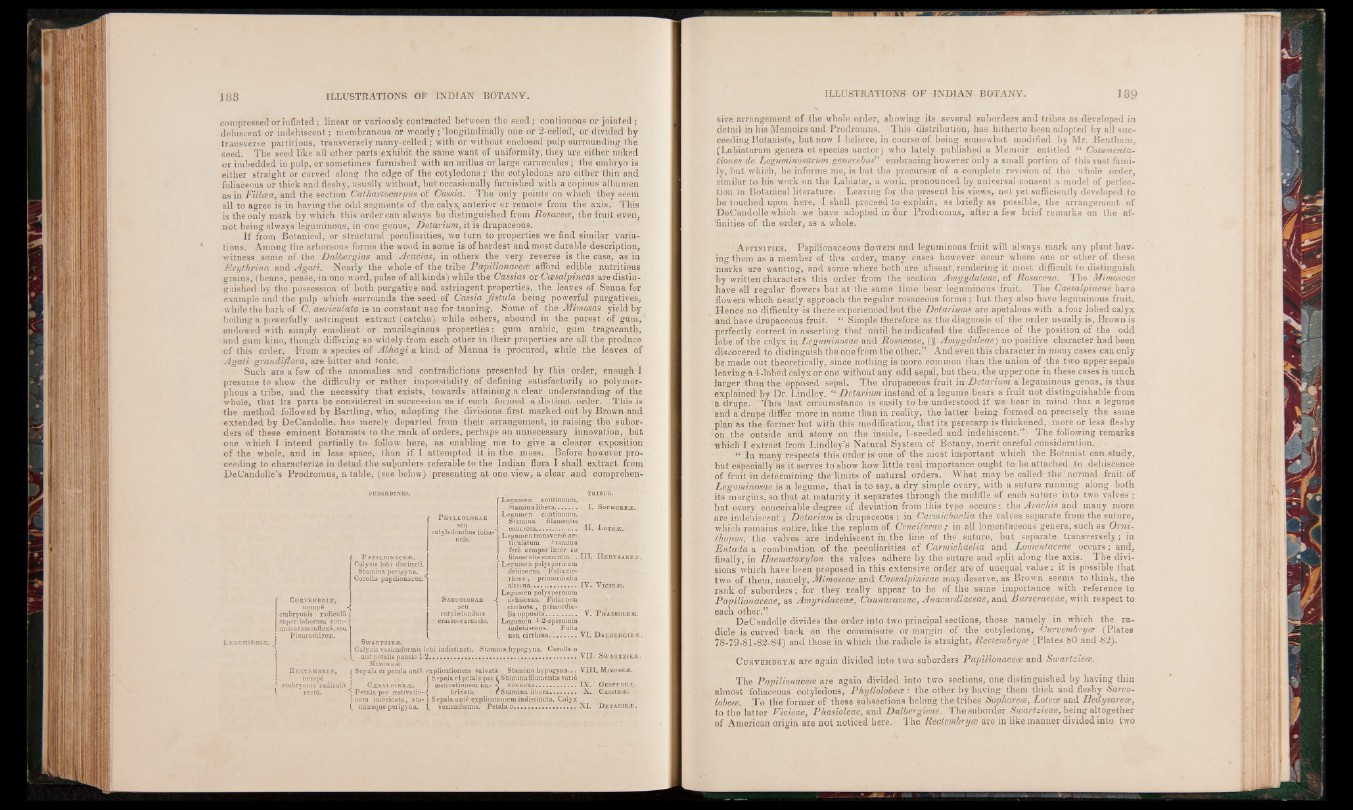

SUBORD1NES.

f P apilionaceæ,

* Calycis lobi d istincti.

S tam in a p e rig y n a .

Co ro lla p a p ilio n a ce a.

T.EGÜMIKOS-ÎE.

P hyllolobae

TRIBUS.

I f L eg um en co n tin u um . Stam in a lib e ra ......... .. I . Sophoreæ.

L eg um en con tin u um.

S tam in a filamentis

CURVEMBRI/E,

n em p è A

emb ry o n is r a d ic u lâ |

su p e r lo borum c om -j

missu ram in d e x a , seu

P leu ro rh iz eæ .

SwA RTZIEÆ.

, C a ly c is vesicæformis

a u t p e ta lis pau cis 1'

Mimoseæ;.

C S e p a la e t p e ta la a n te

cetyledombus 'fölia*; L “ ' “«ansVörVè' 1 1

c ‘ I tieulatum Stamina

I ferè semper inter se .

( filamen tis c o n creta . . I I I . H ed ÿ sa r eæ ,

f L eg um en p o lyspermum

d eh iscen s. F o lia c ir-

r h o s a , p rim o rd ia lia

.a lte r n a ............................ IV . V ic ie æ .

. Legumen polyspermum

S arcolobae -{ dehiscens. Folia non

cirrhosa , primordialia

opposita.. .......... V. P haseoleæ.

Legumen I-2-sperm um

iqdehiscens. Folia

non cirrhosa...................V I . Dabbergieæ,

embryonis radiculâ

ex p lica tio n em v a lv a ta S tam in a h y p o g y n a ... V I I I . Mimoseve.

f S e p a la e t p e ta la p e r C S tam in a filamentis varie

| aestivationem im - connexa.........................IX . Geoffrey.

b ric a ta . c S tam in a l ib e r a .......... .. X . Cassieas.

a j Cæ s a l p in eæ . I

j P e ta la p e r æstivatio—(

, n em im b r ic a ta , s t a - j S e p a la a n te exp lica tio n em in d is tin c ta . Ca ly x

(, m in a q u ep e rig y n a . (. vesicaeformis. P e t a l a ........................................ X I . D e t a iu e j j ,

sive arrangement of the whole order, showing its several suborders and tribes as developed in

detail in his Memoirs and Prodromus. This distribution, has hitherto been adopted by all succeeding

Botanists, but now I believe, in course of being somewhat modified by Mr. Bentham,

(Labiatarum genera et species auctor) who lately published a Memoir entitled (i Commenta-

tiones de heguminosarum generehus” embracing however only a small portion of this vast family,

but which, he informs me, is but the precursor of a complete revision of the whole order,

similar to his work on the Labiatæ, a work, pronounced by universal consent a model of perfection

in Botanical literature. Leaving for the present his views, not yet sufficiently developed to

be touched upon here, I shall proceed to explain, as briefly as possible, the arrangement of

DeCandolle which we have adopted in ôur Prodromus, after a few brief remarks on the af-

■finities of the order, as a whole.

Affinities. Papilionaceous flowers and leguminous fruit will always mark any plant having

them as a member of this order, many cases however occur where one or other of these

marks are wanting, and some where both are absent,rendering it most difficult to distinguish

by written characters this order from the section Am yg daleae, of Rosaceae. The Mimoseae

have all regular flowers but at the same time bear leguminous fruit. The Caesalpineae have

flowers which nearly approach the regular rosaceous forms ; but they also have leguminous fruit.

Hence no difficulty is there experienced but the D eta r ium s are apetalous with a four lobed calyx

and have drupaceous fruit. “ Simple therefore as the diagnosis of the order usually is, Brown is

perfectly correct in asserting that until he indicated the difference of the position of the odd

lobe of the calyx in Leguminosae and Rosaceae, (§ Amyg d a lea e) no positive character had been

discovered to distinguish the one from the other.” And even this character in many cases can only

be made out theoretically, since nothing is more common than the union of the two upper sepals

leaving a4-lobed calyx or one without any odd sepal, but then, the upper one in these cases is much

larger than the opposed sepal. The drupaceous fruit in D e ta r ium a leguminous genus, is thus

explained by Dr. Lindley. “ D eta rium instead of a legume bears a fruit not distinguishable from

a drupe. This last circumstance is easily to be understood if we bear in mind that a legume

and a drupe differ more in name than in reality, the latter being formed on precisely the same

plan as the former but with this modification, that its perecarp is thickened, more or less fleshy

on .the outside and stony on the inside, 1-seeded and indehiscent.” The following remarks

which I extract from Lindley’s Natural System of Botany, merit careful consideration.

“ In many respects this order is1 one of thé most important which the Botanist can study,

hùt especially’as it serves to show how little real importance ought to be attached to dehiscence

of fruit in determining the limits of natural orders. What may be called the normal fruit of

L eguminosae is a legume, that is to say, a dry simple ovary, with a suture running along both

its margins, so that at maturity it separates through the middle of each suture into two valves ;

but every conceivable degree of deviation from this type occurs : the Avachis and many more

are indehiscent ; D e ta r ium is drupaceous ; in Carmichaelia the valves separate from the suture,

which remains entire, like the replum of Cruciferae ; in all lomentaceous genera, such as Orn i-

thopus, the valves are indehiscent in the line of the suture, but separate transversely ; in

E n ta d a a combination of the peculiarities of Carmichaelia and Lomentaceae occurs ; and,

finally, in Haematoxylon the valves adhere by the suture and split along the axis. The divisions

which have been proposed in this extensive order are of unequal value ; it is possible that

two of them, namely, Mimoseae and Caesalpinieae may deserve, as Brown seems to think, the

rank of suborders; for they really appear to be of the same importance with reference to

Papilionaceae, as Amyridaceae, Connaraceae, Anacardiaceae, and Burseraceae, with respect to

each other.’?

DeCandolle divides the order into two principal sections, those namely in which the radicle

is curved back on the commisure or margin of the cotyledons, Curvembryce (Plates

78-79-81-82-84) and those in which the radicle is straight, R ectembryoe (Plates 80 and 82).

Curvembryæ are again divided into two suborders Papilionacece and Sw a rtzieoe .

The Papilionacece are again divided into two sections, one distinguished by having thin

almost foliaceous cotyledons, Phyllolobece : the other by having them thick and fleshy arco-

lobece. To the former of these subsections belong the tribes Sophoreee, Loteoe and Hedÿsareæ,

to the latter Vicieae, Phasioleae, and Dalbergieae. The suborder Sw artzieae, being altogether

of American origin are not noticed here. The Rectembryoe are in like manner divided into two