MAL P IGIA CË.Æ-

M a l p i g i a ? H E T E R A N T H E R A . ( R .W . )

H. Merguienses, carpels surrounded with an orbicular The fruit of our H . indica is also unknown, and as it

thin transparent scarious reticulated wing. differs from Roxburgh’s plant in having the under sur-

In the two first the panicles are described as large, face of the leaves rather thickly clothed with soft ap-

eompound and clothed with appressed hairs, in the last pressed pubescence, not glabrous, it may, when the fruit

they are diffuse, glabrous, with few flowers, on long very * is found prove either Roxburgh’s H. nutans, or a dis-

slender jointed pedicels. tinct species* but for the present must remain undeter-

H. cor data, appears quite distinct from all these, but m*ne^*

the fruit is as yet unknown.

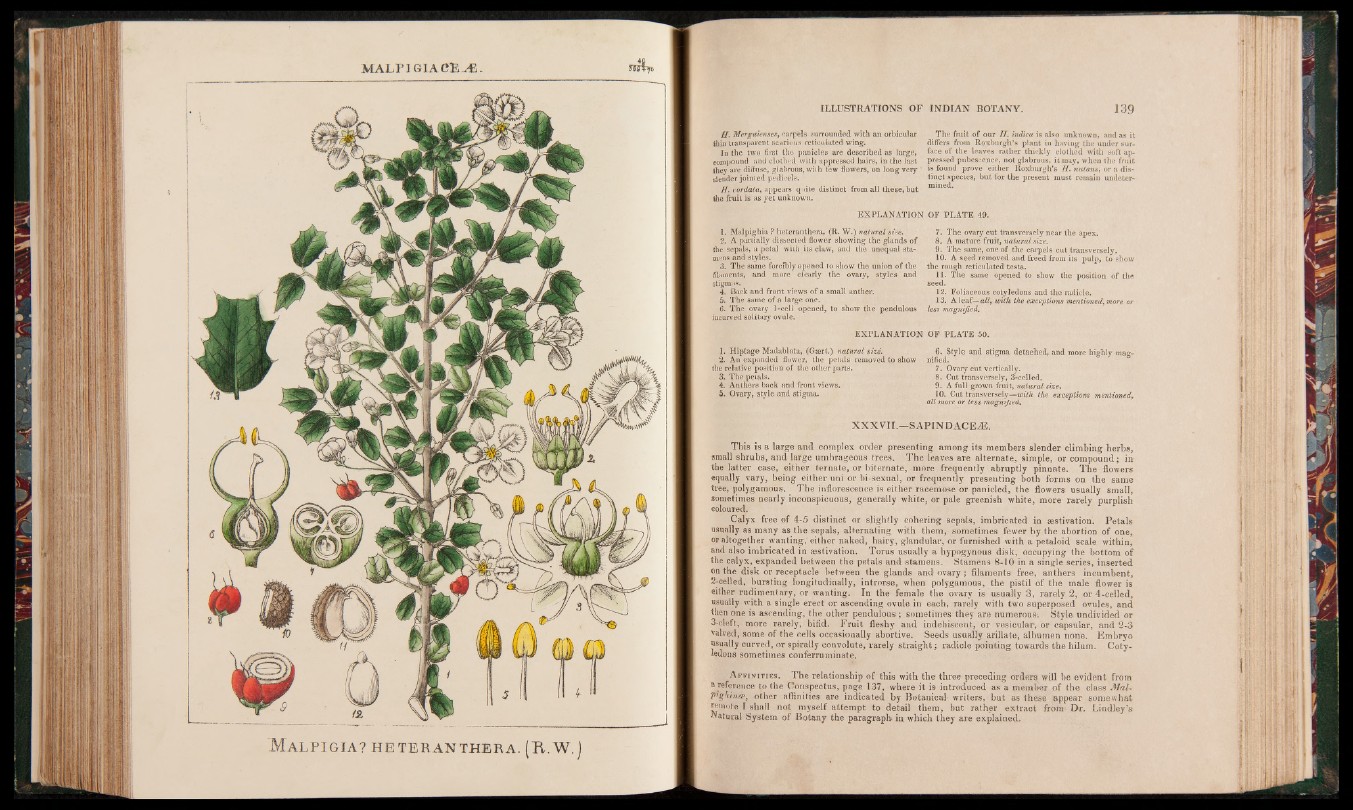

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 49.

I. Malpighia ? heteranthera, (R. W.) natural sise. 7. The ovary cut transversely near the apex.

2. A partially dissected flower showing the glands of 8. A mature fruit, natural size.

the sepals, a petal with its claw, and the unequal sta- 9; The same, one of the carpels cut transversely,

mens and styles. 10. A seed removed and freed from its pulp, to show

3. The same forcibly opened to show the union of the the rough reticulated testa.

filaments, and more clearly the ovary, styles and 11. The same opened to show the position of the

stigmas. seed.

4. Back and front views of a small anther. 12. Foliaceous cotyledons and the radicle.

5. The same of a large one. ;• -13. A leaf—all, with the exceptions mentioned, more or

6. The ovary 1-cell opened, to show the pendulous less magnified.

incurved solitary ovule;

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 50.

1. Hiptage- Madablota, (Gsert.) natural size.

2. An expanded flower, the petals removed to show

the relative position of the other parts.

31. The petals.

4. Anthers back and front views.

5. Ovary, style and stigma.

6. Style and stigma detached, and more highly magnified.

7. Ovary cut vertically.

8. Cut transversely, 3-celled.

9. A full grown fruit, natural size.

10. Cut transversely—with the exceptions mentioned,,

all more or less magnified.

XXXVII.—SAPINDACEÆ.

This is a large and complex order presenting among its members slender climbing herbs,

small shrubs, and large umbrageous trees. The leaves are alternate, simple, or compound; in

the latter case, either ternate, or biternate, more frequently abruptly pinnate. The flowers

equally vary, being either uni or bi sexual, or frequently presenting both forms on the same

tree, polygamous. The inflorescence is either racemose or panicled, the flowers usually small,

sometimes nearly inconspicuous, generally white, or pale greenish white, more rarely purplish

coloured.

Calyx free of 4-5 distinct or slightly cohering sepals, imbricated in aestivation. Petals

usually as many as the sepals, alternating with them, sometimes fewer by the abortion of one,

or altogether wanting, either naked, hairy, glandular, or furnished with a petaloid scale within,

and also imbricated in aestivation-. Torus usually a hypogynous disk, occupying the bottom of

the calyx, expanded between the petals and stamens. Stamens 8-10 in a single series, inserted

on the disk or receptacle between the glands and ovary; filaments free, anthers incumbent,

2- celled, bursting longitudinally, introrse, when polygamous, the pistil of the male flower is

either rudimentary, or wanting. In the female the ovary is usually 3, rarely 2, or 4-celled,

usually with a single erect or ascending ovule in each, rarely with two superposed ovules, and

then one is ascending, the other pendulous ; sometimes they are numerous'. Style undivided or

3- cleft, more rarely, bifid. Fruit fleshy and indehiscent, or vesicular, or capsular, and 2-3

valved, some of the cells occasionally abortive. Seeds usually arillate, albumen none. Embryo

usually curved, or spirally convolute, rarely straight; radicle pointing towards the hilum. Cotyledons

sometimes conferruminate.

Affinities. The relationship of this with the three preceding orders will be evident from

u reference to the Conspectus, page 137, where it is introduced as a member of the class Mal-

pfghinrp, other affinities are indicated by Botanical writers, but as these appear somewhat

p®iRofe I shall not myself attempt to detail them, but rather extract from Dr. Lindley’s

Natural System of Botany the paragraph in which they are explained.