S oil. The following extract from Mr. McClelland’s report descriptive of the- first tea

colony the deputation visited near Cuju will explain hoth the appearance of the spot and the-

■character of the soil. On entering the forest in which the plants were- growing he observes-

p. 19.“

The first remarkable thing that presented itself here; was the peculiar irregularity of the

surface ; which- in places was excavated into natural trenches, and in other situations raised

into rounded accumulations at the roots, and trunks of trees, and clumps of banfboos, as in

the annexed figure. The excavations seemed as if they had been formed artificially, and were

from two; to three, and even four feet deep; of very irregular shapes, and seldom communicating

with each other. After many conjectures, I found the size of the excavations bear exact proportion

to the size and height of the nearest adjoining trees* and that they never appeared im*

mediately under the shade of large branches. The cause then-appeared to be the collection of

rain on the foliage of lofty trees ; from which- the water so collected is precipitated in heavy,

volumes on the loose andy light soil, excavating it in the manner described.

The trenches are from one yard-to ten in length, and generally a yard; or two yards wide ;

and their general figures correspond to the form of the interstices bet ween the-branches above.

The tea plants are most numerous along the margins of these natural excavations, as well on

the accumulations of dry soil raised around the-roots of bamboos. The soil is perfectly loose,

and sinks under the-feet with-a certain degree of elasticity, derived from dense meshes of

succulent fibres; prolonged in every direction from various roots. Its colour is light grey,

perfectly dry and dusty; although the surrounding country was still wet, from the effects of

rain that had-fallen for several days immediately prior to our visit;

Even the trenches were dry, and froirr their not communicating with each other, it seemed

quite evident, that the soil and substratum must be highly porous, and different in this respect

from the structure of the surrounding-surface of the country.

Extending examinations farther, I founds the peculiar character of the-soil in regard to

colour, consistency, and inequality of surface disappear, with the tea plant itself, beyond the

extent of a circular space of about 309 yards in diameter.”

Again he says (p. 22.) of another colony at Nigroo; “ surrounded by tea plants we ascend^

ed the mound, the soil of which is light, fine, and of a yellow colour, having no sandy character”

“ We then traced the plants along the summit of the mound for about 50 yards when

they disappeared where the soil became dark. Now descending to the foot of the mound I

found the tea plant disappear where the soil instead of being sandy or clayey became rich;

and stiff.” Again (p; 28.) at Noadwar. “ Having entered the skirts of a forest which

though not under water, was wet and slippery, and- in some cases deeply- covered with

mud ; we suddenly ascended from the dry. bed' of an occasional water course,- and at first

sight discovered a total change of soil and vegetation. From floundering in mud we

now stood on a light, red; dry, and dusty soil; notwithstanding the rain to- which it was

exposed in common with eveFy part of the country at the time.” Still speaking of the soil at

Noadwar, he continues “ the-colour of the surface is dark yellowish brown, but on* being opened'

it appears much brighter, and on sinking to the depth of three-feet, it changes progressively to

a deep, pure, orange-coloured» sand, quite distinct from any of the other soils; or subsoils in this

part of the district; and in this remarkable situation the tea plants are so numerous that they

constitute a third part, probably, of the entire vegetation of the spot. The red soil disappears

gradually within the limit occupied by the tea plants. T observed the level of the waters in the

wells in this neighbourhood; to be about ten feet below the surface of the ground.

From these examples it will be observed that a light, porous, yellow or redish soil, is the kind

which this plant naturally prefers, but situated in the midst of water and inundation on slightly

elevated mounds, supposed by Mr. McClelland to be themselves sometimes inundated. It will

further be observed that the sites, always of-small extent, occupied by the tea plant’were invariably

in forests under the shade of trees, both of which circumstances ought to-be well attended

to in any attempts made to extend its cultivation.

C limate and E xposure. Under this head-1 find it most difficult to elicit precise-

information from the authorities before me, owing to the contradictory nature of the

details* originating, not in the - want of care on the part of the writers for they have

examined the subject with much attention, but owing to the vast extent of surface

over which, the tea plant is produced, and the remote situations of the countries in which.

it is cultivated. It is now grown with success in Java under the equator, and is said

to be cultivated as far north as the 40° of northern latitude, it is also cultivated on the banks of

the Rio Janeiro in 22| S. latitude. In Siam and Cochin-China between the 10th and 16th

parallels of N, latitude, it is produced in considerable quantity ; while in China, judging from

the enormous quantities exported, and the still greater consumed among themselves, it is clear

it must occupy very excensiv-e tracts- of country, and be subject, to very great varieties of

climate, both as relates to temperature and humidity, and in my opinion, goes far to prove that it

may be cultivated with success in almost any tropical climate, combining humidity with a moderate

range of temperature. It. is true we are told that unless the climate partakes more of the temperate

than tropical character, that the tea produced will be deficient in some of its most esteemed

qualities, the fine Aroma &c.., but these I suspect it owes more to soil and skilful

preparation of the leaves when gathered, than to the character of the climate under which they

have been produced. Peculiarities of soil, on which plants are grown, exert much influence on

the qualities of the products of vegetation, some plants growing in a very humid or marshy soil,

are in tensely acrid, the common garden celery for example, but which when raised on a rich dry soil

become mild and esculent. Other plants present the opposite phenomenon, that of losing their

acrid or aromatic properties, when removed from a dry to a wet soil. To quote examples of the

effect of soil in modifying the qualities of vegetable products would be to waste time, as every

one s experience and reading must have furnished him cases in point, and that too, under circum-

stances in all other respects the same. In like manner there is every reason to believe that, the

different qualities of tea are owing, not so much to1 differences of climate, as of soil, the

sickly or vigorous condition of the plant when gathered, and the more or less perfect course of

preparation, to which it has been subjected.

In throwing out these remarks. I da not. mean to infer that the plant might, under proper

cultivation, be made to produce tea of good quality under any climate in which it can be made to^

grow, but with the view of encouraging trials in such climates as the Indian Peninsula supplies,

and discouraging the idea that, because we have not a climate within these limits, with a range

of temperature extending from 30° to 80° of Fahrenheit’s scale, that therefore it would be in

v.ain to attempt its culture. This I do, because the regulation of the climate not being within our

power, to suppose it opposed; to our efforts, is at once to-declare all.attempts-at introduction futile^

but the selection, and modification., by.artificial means, of-the qualities of the soil, being an every

day occurrence in agriculture,- holds out good reason-to-hope for success if opposed by that only.-

To show however that in so far as temperature is concerned, we are not unprovided wilh

localities enjoying a climate if not the best, yet far from unsuitable for the culture of this shrub, L

extract from Mr. Griffiths’ report some tables showing the mean temperature of Canton and

jichya from which it will be perceived that both Malabar and Mysore are not very different,

while the former, as well as the south-west coast of Ceylon, enjoys a climate but little, if at all less-

humid, than is experienced in the vicinity of Canton.

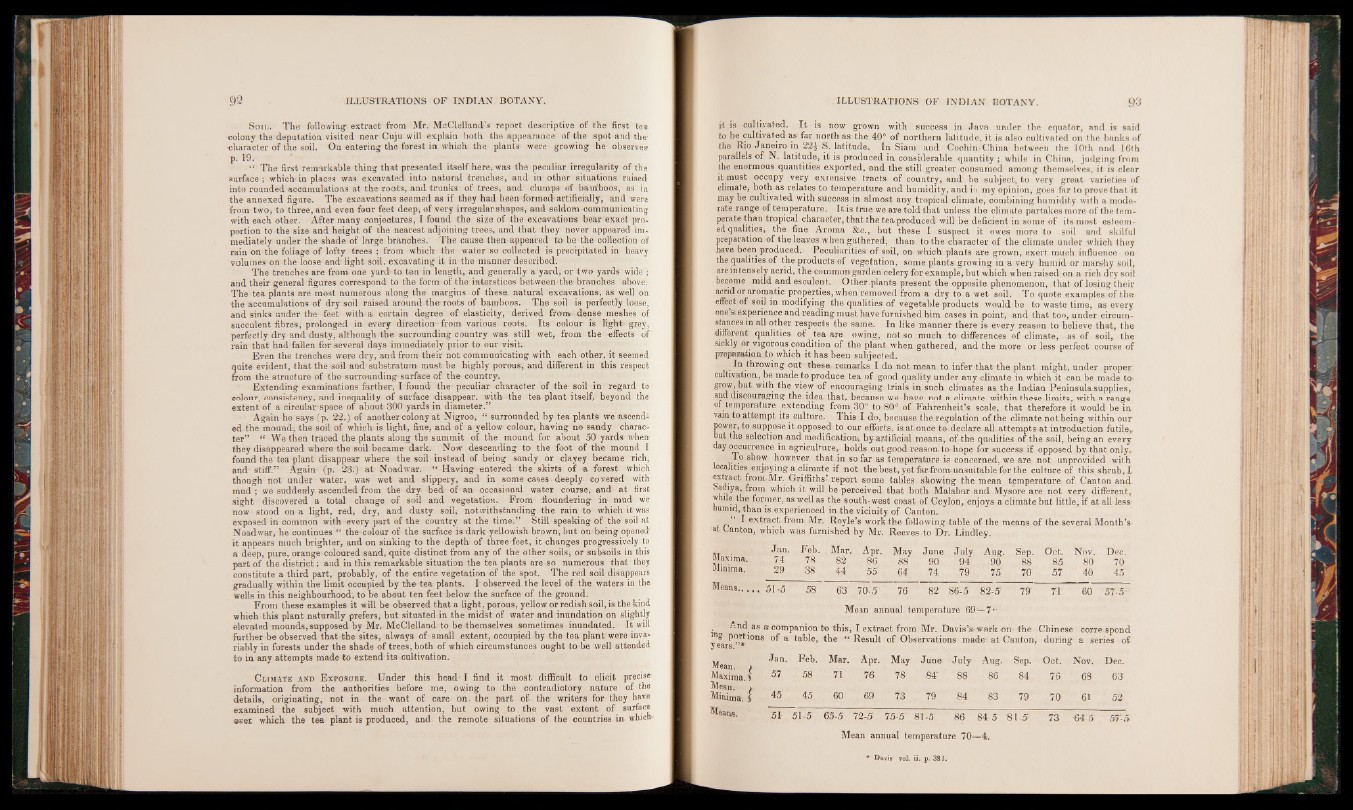

‘ 1 extract from Mr. Royle’s work the following table of the means of the several Month’s

at Canton, which was furnished by Mr. Reeves to Dr. Lindley.

Maxima;

Minima.

Means...,

Jan. Feb. . Mar. Apr. May June July Aug. Sep. Oct. N op. Dec.

74 78 82 86 88 90 94 90 88 85 80 70

29 38 44 55 64' 74 .79 75 70 57 | 40 45

51-5 58 63 70-5 76 82 86-5 82-5* 79' 71’ 60 57-5'

Mean annual temperature 69—7*

y ears.”*

Mean. » Maxima. 4 Mean, i

Minima. 4

Means,

of a table, the H Result of Observations made' at Canton, during a series of

Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May June July Aug. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec.

57 58 71 76 78 84" ' 88 86 84 76 68 63

45 45 60 69 73 . 79 84 83 79 70 61 52

51- 51-5 65-5 72 -5 75-5' 81-5 86 84-5 81-5 73 ■645 57-5

Mean annual temperature 70—4.

* D av is vol. ii. p . 38 L