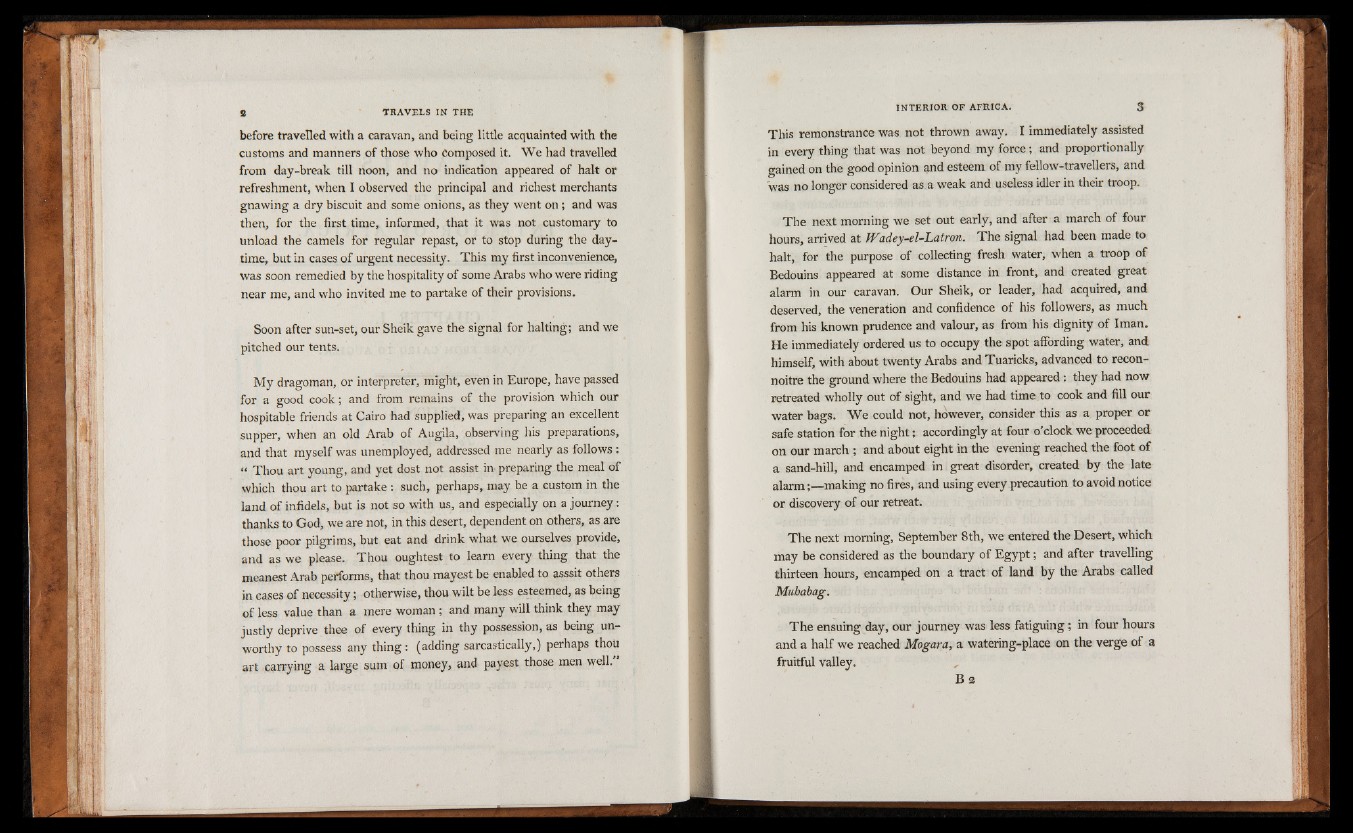

before travelled with a caravan, and being little acquainted with the

customs and manners of those who Composed it. We had travelled

from day-break till noon, and no indication appeared of halt or

refreshment, when I observed the principal and richest merchants

gnawing a dry biscuit and some onions, as they went on; and was

then, for the first time, informed, that it was not customary to

unload the camels for regular repast, or to stop during the daytime,

but in cases of urgent necessity. This my first inconvenience,

was soon remedied by the hospitality of some Arabs who were riding

near me, and who invited me to partake of their provisions.

Soon after sun-set, our Sheik gave the signal for halting; and we

pitched our tents.

My dragoman, or interpreter, might, even in Europe, have passed

for a good cook; and from remains of the provision which our

hospitable friends at Cairo had supplied, was preparing an excellent

supper, when an old Arab of Augila, observing his preparations,

and that myself was unemployed, addressed me nearly as follows :

“ Thou art young, and yet dost not assist in preparing the meal of

which thou art to partake: such, perhaps, may he a custom in the

land of infidels, but is not so with us, and especially on a journey:

thanks to God, we are not, in this desert, dependent on others, as are

those poor pilgrims, but eat and drink what we ourselves provide,

and as we please. Thou oughtest to learn every thing that the

meanest Arab performs, that thou mayest be enabled to asssit others

in cases of necessity; otherwise, thou wilt be less esteemed, as being

of less value than a mere woman; and many will think they may

justly deprive thee of every thing in thy possession, as being unworthy

to possess any thing: (adding sarcastically,) perhaps thoU

art carrying a large sum of money, and payest those men well.

This remonstrance was not thrown away. I immediately assisted

in every thing that was not beyond my force; and proportionally

gained on the good opinion and esteem of my fellow-travellers, and

was no longer considered as a weak and useless idler in their troop.

The next morning we set out early, and after a march of four

hours, arrived at JVadey-el-Lutron. The signal had been made to

halt, for the purpose of collecting fresh water, when a troop of

Bedouins appeared at some distance in front, and created great

alarm in our caravan. Our Sheik, or leader, had acquired, and

deserved, the veneration and confidence of his followers, as much

from his known prudence and valour, as from his dignity of Iman.

He immediately ordered us to occupy the spot affording water, and

himself, with about twenty Arabs and Tuaricks, advanced to reconnoitre

the ground where the Bedouins had appeared : they had now

retreated wholly out of sight, and we had time to cook and fill our

water bags. We could not, however, consider this as a proper or

safe station for the night; accordingly at four o’clock we proceeded

on our march ; and about eight in the evening reached the foot of

a sand-hill, and encamped in great disorder, created by the late

alarm;— making no fires, and using every precaution to avoid notice

or discovery of our retreat.

The next morning, September 8th, we entered the Desert, which

may be considered as the boundary of Egypt; and after travelling

thirteen hours, encamped on a tract of land by the Arabs called

Mubabag.

The ensuing day, our journey was less fatiguing; in four hours

and a half we reached Mogara, a watering-place on the verge of a

fruitful valley.

B s