and the neglect of wearing warmer clothing after sunset,

for weak lungs are liable to sniffer from the sudden

change of temperature that then ensues. But, on the

other hand, the possessors of weak chests and moderately

diseased lungs, to whom a European winter is a

positive danger, may with a modicum of care live in

physical ease and comfort breathing the glorious air of

this high Transvaalian tableland. It was to the want

of proper sanitary arrangements that the epidemic of

1889-1890 was doubtless due. This took the form of

typhoid fever, with a frequent complication of pneumonia

which attacked both lungs at the same time.

Two judges, two doctors, and a large number of Europeans

were quickly carried off, and the mortality was

greater at Johannesburg than in Pretoria. At present

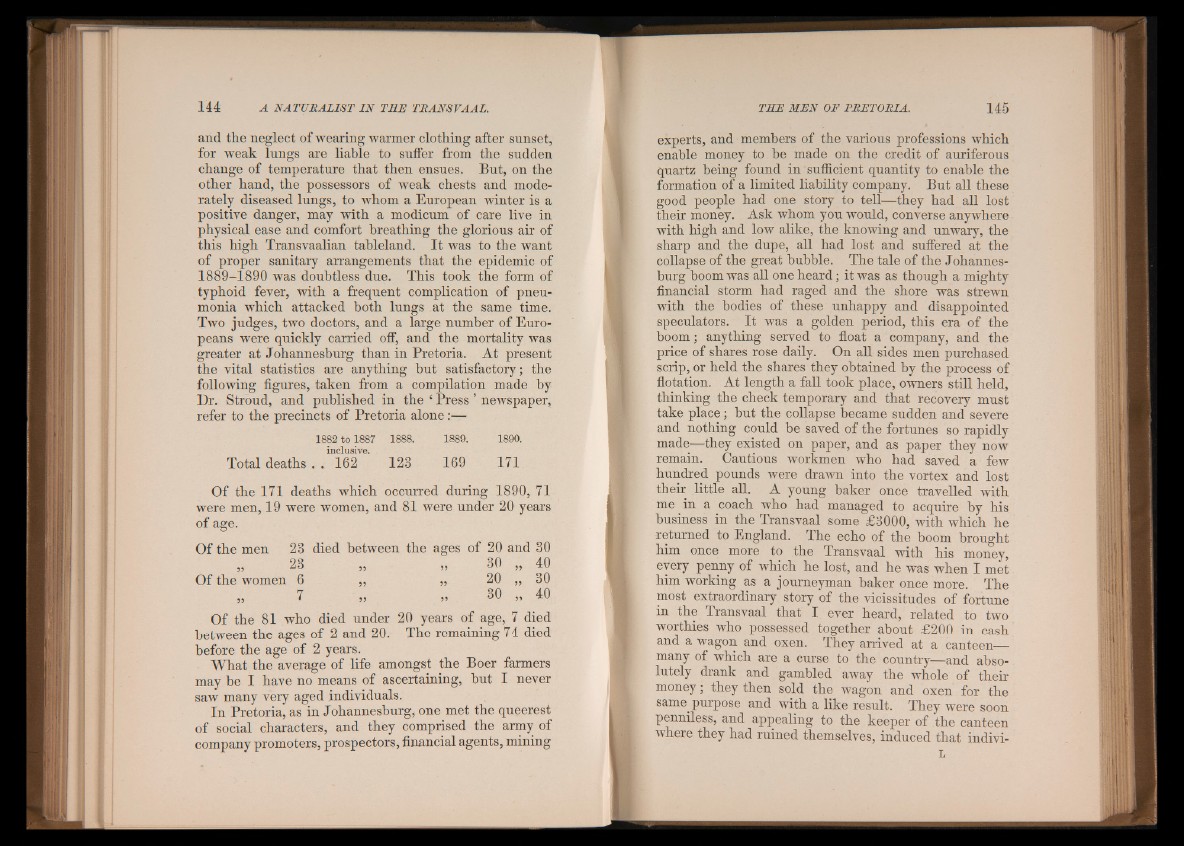

the vital statistics are anything but satisfactory; the

following figures, taken from a compilation made by

Dr. Stroud, and published in the c Press ’ newspaper,

refer to the precincts of Pretoria alone:—

1882 to 1887 1888. 1889. 1890.

inclusive.

Total deaths . . 162 123 169 171

Of the 171 deaths which occurred during 1890, 71

were men, 19 were women, and 81 were under 20 years

of age.

Of the men 23 died between the ages of 20 and 30

23 „ „ 30 „ 40

Of the women 6 „ „ 20 „ 30

7 „ „ 30 „ 40

Of the 81 who died under 20 years of age, 7 died

between the ages of 2 and 20. The remaining 74 died

before the age of 2 years.

What the average of life amongst the Boer farmers

may he I have no means of ascertaining, hut I never

saw many very aged individuals.

In Pretoria, as in Johannesburg, one met the queerest

of social characters, and they comprised the army of

company promoters, prospectors, financial agents, mining

experts, and members of the various professions which

enable money to be made on the credit of auriferous

quartz being found in sufficient quantity to enable the

formation of a limited liability company. But all these

good people had one story to tell—they had all lost

their money. Ask whom you would, converse anywhere

with high and low alike, the knowing and unwary, the

sharp and the dupe, all had lost and suffered at the

collapse of the great bubble. The tale of the Johannesburg

boom was all one heard; it was as though a mighty

financial storm had raged and the shore was strewn

with the bodies of these unhappy and disappointed

speculators. It was a golden period, this era of the

boom; anything served to float a company, and the

price of shares rose daily. On all sides men purchased

scrip, or held the shares they obtained by the process of

flotation. At length a fall took place, owners still held,

thinking the check temporary and that recovery must

take place; but the collapse became sudden and severe

and nothing could he saved of the fortunes so rapidly

made—they existed on paper, and as paper they now

remain. Cautious workmen who had saved a few

hundred pounds were drawn into the vortex and lost

their little all. A young baker once travelled with

me in a coach who had managed to acquire by his

business in the Transvaal some £3000, with which he

returned to England. The echo of the boom brought

him once more to the Transvaal with his money,

every penny of which he lost, and he was when I met

him working as a journeyman baker once more. The

most extraordinary story of the vicissitudes of fortune

in the Transvaal that I ever heard, related to two

worthies who possessed together about £200 in cash

and a wagon and oxen. They arrived at a canteen—

many of which are a curse to the country—and absolutely

drank and gambled away the whole of their

money; they then sold the wagon and oxen for the

same purpose and with a like result. They were soon

penniless, and appealing to the keeper of the canteen

where they had ruined themselves, induced that indivi-

L