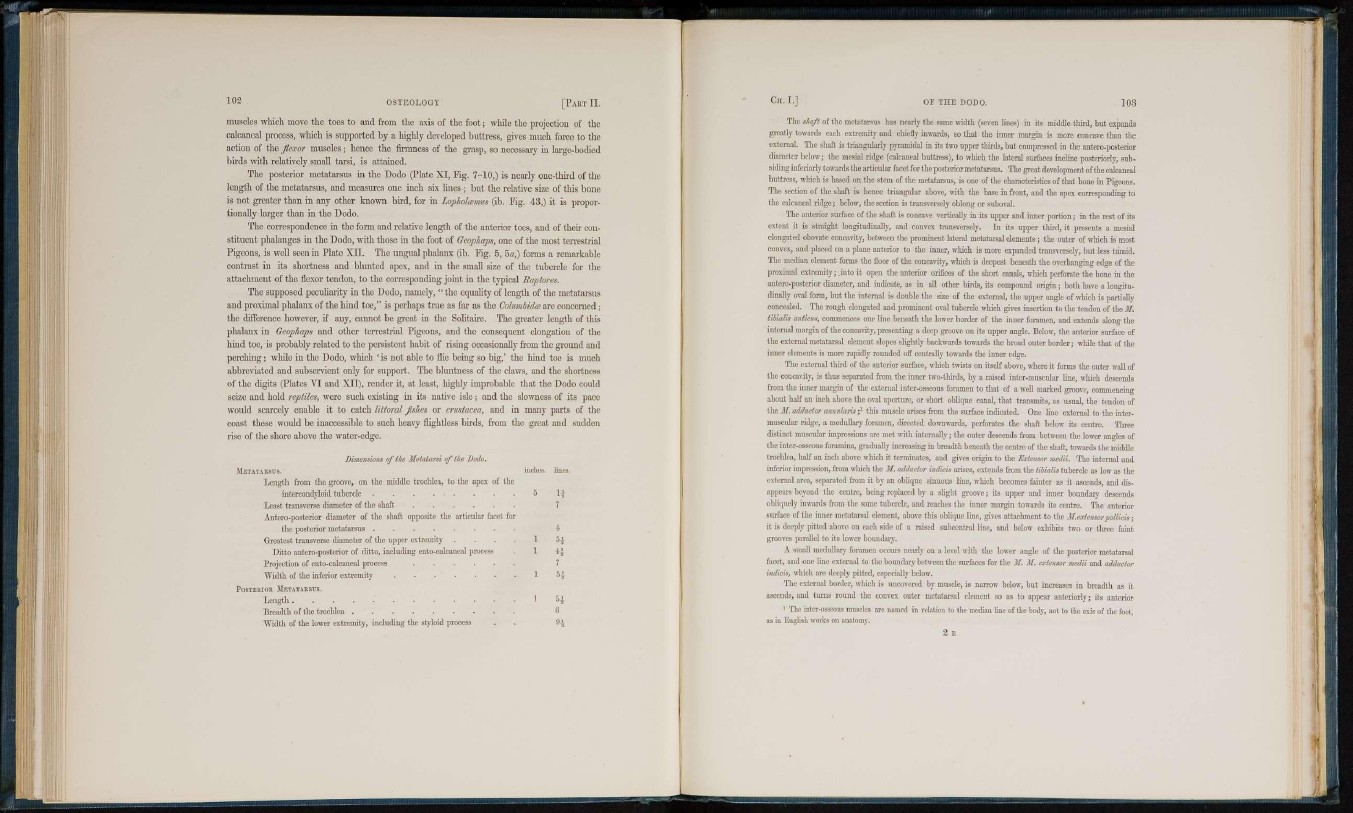

Dimensions of the Metatarsi of the Dodo.

METATARSUS. inches, lines.

Length from the groove, on the middle trochlea, to the apex of the

intercondyloid tubercle . . . . . . . . . 5 1-J

Least transverse diameter of the shaft 7

Antcro-postcrior diameter of the shaft opposite the articular facet for

the posterior metatarsus . . . . . . . . 4

Greatest transverse diameter of the upper extremity . . . . 1 5-J

Ditto antcro-postcrior of ditto, including cnto-calcaneal process . 1 4 J

Projection of cnto-calcaneal process 7

Width of the inferior extremity 1 5^

POSTERIOR METATARSUS.

Length. 1 H

Breadth of the trochlea 6

Width of the lower extremity, including the styloid process . . 9-|

The shaft of the metatarsus has nearly the same width (seven lines) in its middle third, but expands

greatly towards each extremity and chiefly inwards, so that the inner margin is more concave than the

external. The shaft is triangularly pyramidal in its two upper thirds, but compressed in t he antcro-posterior

diameter below; the mesial ridge (calcaneal buttress), to which the lateral surfaces incline posteriorly, subsiding

inferiorly towards the articular facet for the posterior metatarsus. The great development of the calcaneal

buttress, which is based on the stem of the metatarsus, is one of the characteristics of that bone in Pigeons.

The section of the shaft is hence triangular above, with the base in front, and the apex corresponding to

the calcaneal ridge; below, the section is transversely oblong or suboval.

The anterior surface of the shaft is concave vertically in its upper and inner portion; in the rest of its

extent it is straight longitudinally, and convex transversely. In its upper third, it presents a mesial

elongated obovate concavity, between the prominent lateral metatarsal elements ; the outer of which is most

convex, and placed on a plane anterior to the inner, which is more expanded transversely, but less tumid.

The median clement forms the floor of the concavity, which is deepest beneath the overhanging edge of the

proximal extremity; .into it open the anterior orifices of the short canals, winch perforate the bone in the

anteroposterior diameter, and indicate, as in all other birds, its compound origin; both have a longitudinally

oval form, but the internal is double the size of the external, the upper angle of which is partially

concealed. The rough elongated and prominent oval tubercle which gives insertion to the tendon of the M.

tibialis anticiis, commences one line beneath the lower border of the inner foramen, and extends along the

internal margin of the concavity, presenting a deep groove on its upper angle. Below, the anterior surface of

the external metatarsal element slopes slightly backwards towards the broad outer border; while that of the

inner elements is more rapidly rounded off centrally towards the inner edge.

The external third of the anterior surface, which twists on itself above, where it forms the outer wall of

the concavity, is thus separated from the inner two-thirds, by a raised intcr-muscular line, which descends

from the inner margin of the external inter-osseous foramen to that of a well marked groove, commencing

about half an inch above the oval aperture, or short oblique canal, that transmits, as usual, the tendon of

the M. adductor annularis j 1 this muscle arises from the surface indicated. One line external to the intermuscular

ridge, a medullary foramen, directed downwards, perforates the shaft below its centre. Three

distinct muscular impressions are met with internally; the outer descends from between the lower angles of

the inter-osseous foramina, gradually increasing in breadth beneath the centre of the shaft, towards the middle

trocldca, half an inch above which it terminates, and gives origin to the Extensor medii. The internal and

inferior impression, from which the M. adductor indicis arises, extends from the tibialis tubercle as low as the

external area, separated from it by an oblique sinuous line, which becomes fainter as it ascends, and disappears

beyond the centre, being replaced by a slight groove; its upper and inner boundary descends

obliquely inwards from the same tubercle, and reaches the inner margin towards its centre. The anterior

surface of the inner metatarsal element, above this oblique line, gives attachment to the M.cxtensorpollicis;

it is deeply pitted above on each side of a raised subcentral line, and below exhibits two or three faint

grooves parallel to its lower boundary.

A small medullar)- foramen occurs nearly on a level with the lower angle of the posterior metatarsal

facet, and one line external to the boundary between the surfaces for the M. M. extensor medii and adductor

indicis, which are deeply pitted, especially below.

The external border, which is uncovered by muscle, is narrow below, but increases in breadth as it

ascends, and turns round the convex outer metatarsal element so as to appear anteriorly; its anterior

1 The inter-osseous muscles are named in relation to the median line of the body, not to the axis of the foot,

as in English works on anatomy.

2 E

muscles which move the toes to and from the axis of the foot; while the projection of the

calcaneal process, which is supported by a highly developed buttress, gives much force to the

action of the flexor muscles; hence the firmness of the grasp, so necessary in large-bodied

birds with relatively small tarsi, is attained.

The posterior metatarsus in the Dodo (Plate X I , Fig. 7 - 1 0 , ) is nearly one-third of the

length of the metatarsus, and measures one inch six lines; but the relative size of this bone

is not greater than in any other known bird, for in Lopholamus (ib. Pig. 4 3 , ) it is proportionally

larger than in the Dodo.

The correspondence in the form and relative length of the anterior toes, and of their constituent

phalanges in the Dodo, with those in the foot of Gcophaps, one of the most terrestrial

Pigeons, is well seen in Plate X I I . The ungual phalanx (ib. Pig. 5, 5a,) forms a remarkable

contrast in its shortness and blunted apex, and in the small size of the tubercle for the

attachment of the flexor tendon, to the corresponding joint in the typical Baptores.

The supposed peculiarity in the Dodo, namely, " the equality of length of the metatarsus

and proximal phalanx of the hind toe," is perhaps true as far as the Columbidcc arc concerned;

the difference however, if any, cannot be great in the Solitaire. The greater length of this

phalanx in Geopliaps and other terrestrial Pigeons, and the consequent elongation of the

hind toe, is probably related to the persistent habit of rising occasionally from the ground and

perching; while in the Dodo, which ' is not able to flie being so big,' the hind toe is much

abbreviated and subservient only for support. The bluntness of the claws, and the shortness

of the digits (Plates V I and X I I ) , render it, at least, highly improbable that the Dodo could

seize and hold reptiles, were such existing in its native isle; and the slowness of its pace

would scarcely enable it to catch littoral fishes or Crustacea, and in many parts of the

coast these would be inaccessible to such heavy flightless birds, from the great and sudden

rise of the shore above the water-edge.