PASSERES. ERIN GILLIDÆ.

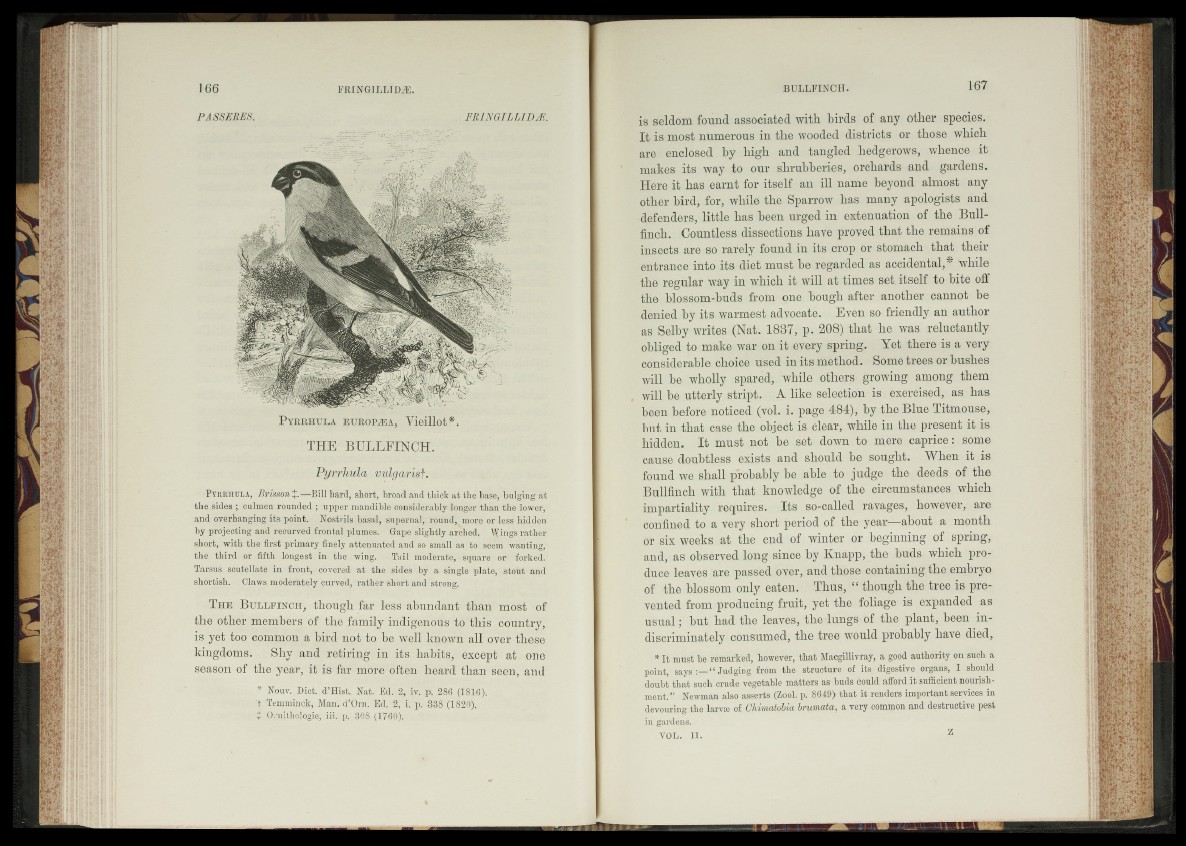

P y r r h u la e u r o pæ a , Vieillot*.

THE BULLFINCH.

Pyrrhula vulgarisé.

Pyrrhula, Brisson%.—Bill hard, short, broad and thick at the base, bulging at

the sides ; culmen rounded ; upper mandible considerably longer than the lower,

and overhanging its point. Nostrils basal, supernal, round, more or less hidden

by projecting and recurved frontal plumes. Gape slightly arched. Wings rather

short, with the first primary finely attenuated and so small as to seem wanting,

the third or fifth longest in the wing. Tail moderate, square or forked.

Tarsus scutellate in front, covered at the sides by a single plate, stout and

shortish. Claws moderately curved, rather short and strong.

T h e B u l l f in c h , though far less abundant than most of

the other members of the family indigenous to this country,

is yet too common a bird not to be well known all over these

kingdoms. Shy and retiring in its habits, except at one

season of the year, it is far more often heard than seen, and

* Nouv. Diet. d’Hist. Nat. Ed. 2, iv. p. 286 (1816).

t Temminck, Man. d’Orn. Ed. 2, i. p. 338 (1820).

î Ornithologie, iii. p. 308 (1760).

is seldom found associated with birds of any other species.

It is most numerous in the wooded districts or those which

are enclosed by high and tangled hedgerows, whence it

makes its way to our shrubberies, orchards and gardens.

Here it has earnt for itself an ill name beyond almost any

other bird, for, while the Sparrow has many apologists and

defenders, little has been urged in extenuation of the Bullfinch.

Countless dissections have proved that the remains of

insects are so rarely found in its crop or stomach that their

entrance into its diet must he regarded as accidental,* while

the regular way in which it will at times set. itself to bite off

the blossom-buds from one hough after another cannot be

denied by its warmest advocate. Even so friendly an author

as Selby writes (Nat. 1837, p. 208) that he was reluctantly

obliged to make war on it every spring. Yet there is a very

considerable choice used in its method. Some trees or bushes

will be wholly spared, while others growing among them

will be utterly stript. A like selection is exercised, as has

been before noticed (vol. i. page 484), by the Blue Titmouse,

but in that case the object is clear, while in the present it is

hidden. It must not be set down to mere caprice: some

cause doubtless exists and should be sought. When it is

found we shall probably be able to judge the deeds of the

Bullfinch with that knowledge of the circumstances which

impartiality requires. Its so-called ravages, however, are

confined to a very short period of the year—about a month

or six weeks at the end of winter or beginning of spring,

and, as observed long since by Knapp, the buds which produce

leaves are passed over, and those containing the embryo

of the blossom only eaten. Thus, “ though the tree is prevented

from producing fruit, yet the foliage is expanded as

usual; but had the leaves, the lungs of the plant, been indiscriminately

consumed, the tree would probably have died,

* It must be remarked, however, that Macgillivray, a good authority on such a

point, says “ Judging from the structure of its digestive organs, I should

doubt that such crude vegetable matters as buds could afford it sufficient nourishment.”

Newman also asserts (Zool. p. 8649) that it renders important services in

devouring the larvae of ChimatoUa brumata, a very common and destructive pest

in gardens.

VOL. H , Z