and convey the food to the gullet, or oesophagus, and hinder

its return so as to enter the windpipe. This orifice is

bounded on either side by the arytsenoid cartilages, seen

more plainly in Fig. 2 (6, 6), where the greater part of the

cricoid cartilage (a, a, a) has been removed, together with

the investments of the windpipe (c), that the bony rings of

which this is composed may appear more clearly. Figs. 3

and 4 illustrate the muscles which control the size of the

orifice, and constitute one of the accessory means by which

the sound of the voice is regulated. Of these there are

two pairs. The first, of which a portion is shewn in (Fig. 8

(a) and the whole displayed in Fig. 4 (a, a), extend from

the upper portion of the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 2, a) along

the two branches of the arytaenoid cartilages (Fig. 2, b) in

the outer edge of each of which they are respectively

inserted, and serve to close the orifice. The second,

sufficiently visible in Fig. 3 (6, 6), are those which open the

orifice, and arise from the lateral and posterior portion of

the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 2, a), and their fibres, passing

over the closing muscles just described, are inserted on the

inner edge of each arytaenoid cartilage (Fig. 2, 6).

The tube of the windpipe, or trachea, is composed of two

membranes enclosing numerous rings forming a cylinder

from end to end. At first cartilaginous, they become bony

as the bird grows older, and their ossification begins in

front and gradually extends backward towards the gullet*.

So far then there is no essential difference between the

Raven and other birds in the parts described.

The inferior larynx or syrinx, which is the real seat of

^ In certain birds ossification of all the tracheal rings is not completed.

Various inequalities of diameter and convolutions of the tube (some of which

will be hereafter described and figured) also occur, producing, as might be

expected particular effects on the voice. Generally the proportionate length of

the trachea deserves consideration, for shrill notes are produced by short tubes

and mce versâ. On the structure of the tube, too, certain effects depend. As a

general rule, though not without exceptions, birds which possess strong and

broad cartilages or bony rings have a monotonous and loud voice, while slenderer

rings with wider interspaces allow a freedom of motion producing a corresponding

variety in the scale of tone. ' P

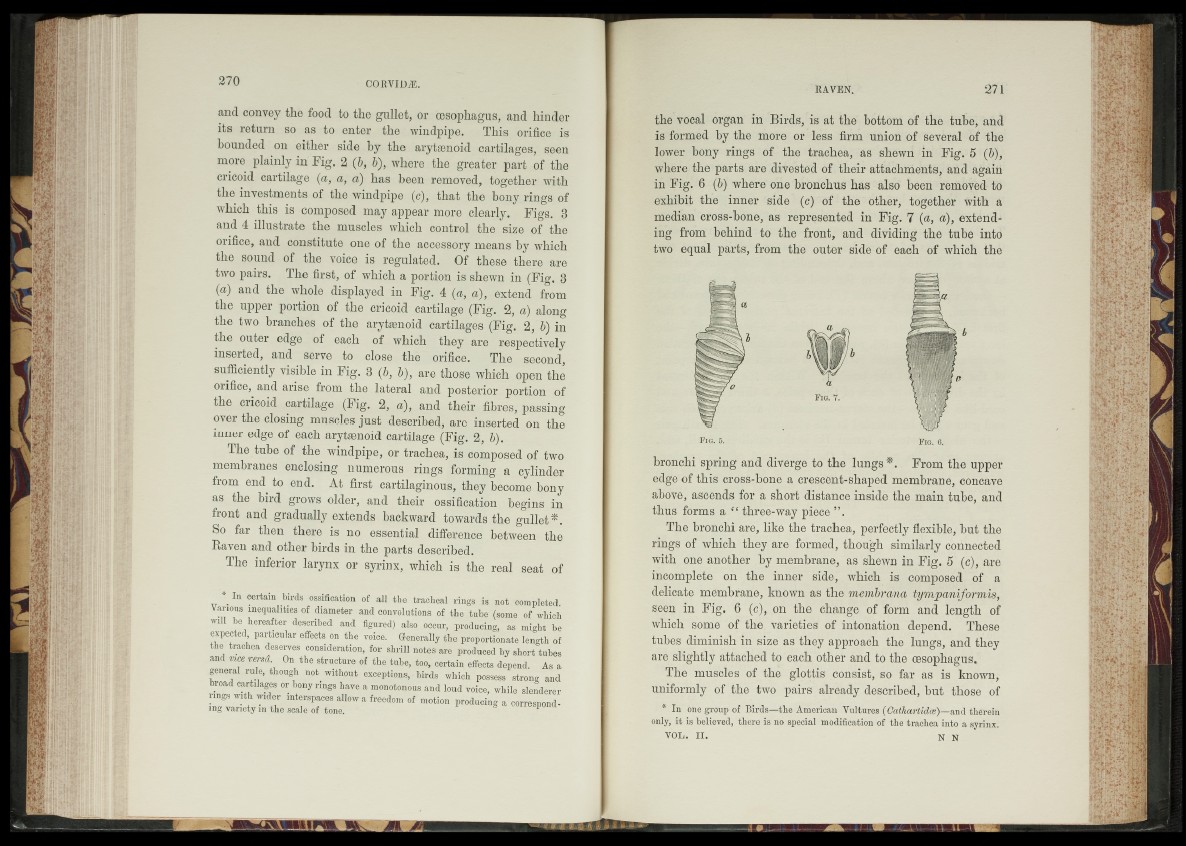

the vocal organ in Birds, is at the bottom of the tube, and

is formed by the more or less firm union of several of the

lower bony rings of the trachea, as shewn in Fig. 5 (b),

where the parts are divested of their attachments, and again

in Fig. 6 (6) where one bronchus has also been removed to

exhibit the inner side (c) of the other, together with a

median cross-bone, as represented in Fig. 7 (a, a), extending

from behind to the front, and dividing the tube into

two equal parts, from the outer side of each of which the

Pig. 5. Fig. 6,

bronchi spring and diverge to the lungs*. From the upper

edge of this cross-bone a crescent-shaped membrane, concave

above, ascends for a short distance inside the main tube, and

thus forms a “ three-way piece ” .

The bronchi are, like the trachea, perfectly flexible, but the

rings of which they are formed, though similarly connected

with one another by membrane, as shewn in Fig. 5 (c), are

incomplete on the inner side, which is composed of a

delicate membrane, known as the membrana tympaniformis,

seen in Fig. 6 (c), on the change of form and length of

which some of the varieties of intonation depend. These

tubes diminish in size as they approach the lungs, and they

are slightly attached to each other and to the oesophagus.

The muscles of the glottis consist, so far as is known,

uniformly of the two pairs already described, but those of

* In one group of Birds—the American Vultures (Cathartidce)—and therein

only, it is believed, there is no special modification of the trachea into a syrinx.