PA SSE RES. FRING1LL1DÆ.

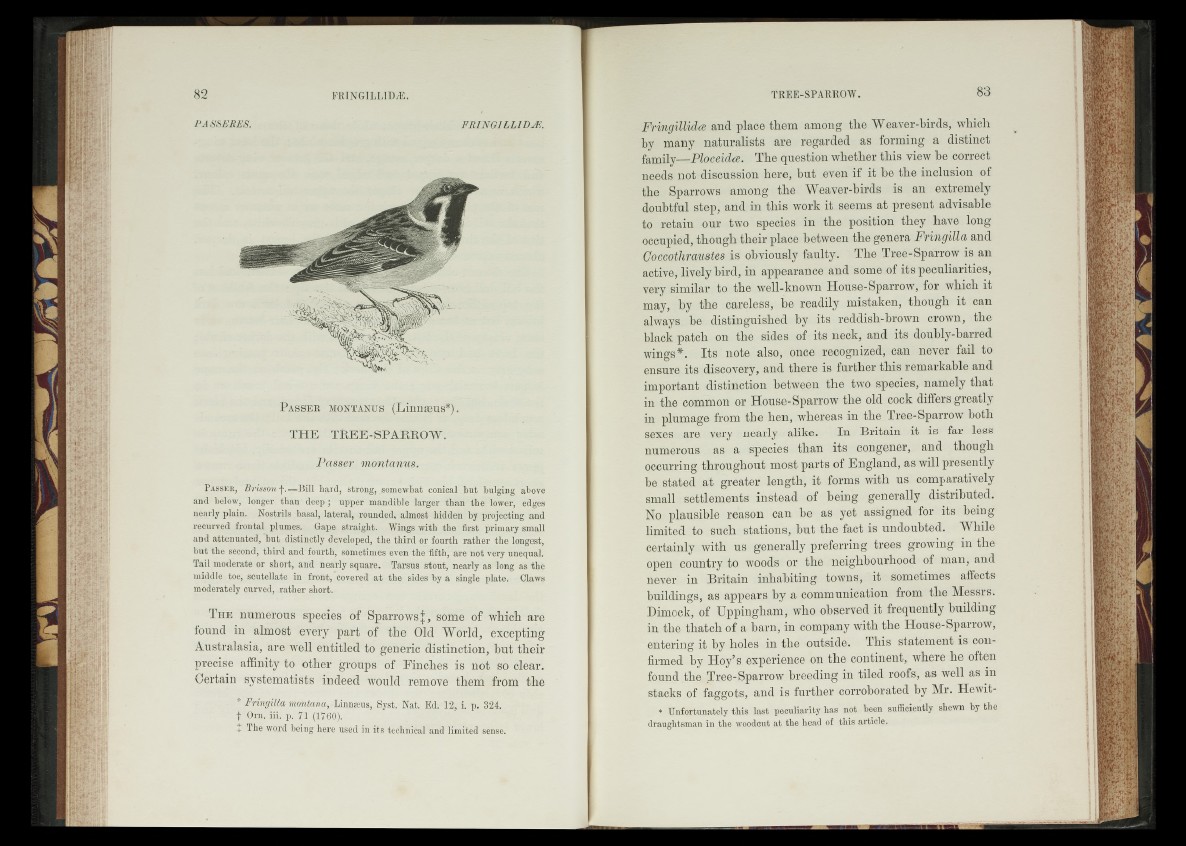

P a s s e r montanus (Linnaeus*).

THE TREE-SPARROW.

Passer montanus.

Passer, Brisson f .—Bill hard, strong, somewhat conical hut bulging above

and below, longer than deep; upper mandible larger than the lower, edges

nearly plain. Nostrils basal, lateral, rounded, almost hidden by projecting and

recurved frontal plumes. Gape straight. Wings with the first primary small

and attenuated, but distinctly developed, the third or fourth rather the longest,

but the second, third and fourth, sometimes even the fifth, are not very unequal.

Tail moderate or short, and nearly square. Tarsus stout, nearly as long as the

middle toe, scutellate in front, covered at the sides by a single plate. Claws

moderately curved, rather short.

T h e numerous species of Sparrows J, some of which are

found in almost every part of the Old World, excepting

Australasia, are well entitled to generic distinction, but their

precise affinity to other groups of Finches is not so clear.

Certain systematists indeed would remove them from the

* Fringilla mon tan a, Linnseus, Syst. Nat. Ed. 12, i. p. 324.

f Orn. iii. p. 71 (1760).

-^e w°rd being here used in its technical and limited sense.

Fringillidce and place them among the Weaver-birds, which

by many naturalists are regarded as forming a distinct

family—Ploceidce. The question whether this view he correct

needs not discussion here, but even if it be the inclusion of

the Sparrows among the Weaver-birds is an extremely

doubtful step, and in this work it seems at present advisable

to retain our two species in the position they have long

occupied, though their place between the genera Fringilla and

Coccothraustes is obviously faulty. The Tree-Sparrow is an

active, lively bird, in appearance and some of its peculiarities,

very similar to the well-known House-Sparrow, for which it

may, by the careless, be readily mistaken, though it can

always be distinguished by its reddish-brown crown, the

black patch on the sides of its neck, and its doubly-barred

wings*. Its note also, once recognized, can never fail to

ensure its discovery, and there is further this remarkable and

important distinction between the two species, namely that

in the common or House-Sparrow the old cock differs greatly

in plumage from the hen, whereas in the Tree-Sparrow both

sexes are very nearly alike. In Britain it is far less

numerous as a species than its congener, and though

occurring throughout most parts of England, as will presently

be stated at greater length, it forms with us comparatively

small settlements instead of being generally distributed.

No plausible reason can be as yet assigned for its being

limited to such stations, but the fact is undoubted. While

certainly with us generally preferring trees growing in the

open country to woods or the neighbourhood of man, and

never in Britain inhabiting towns, it sometimes affects

buildings, as appears by a communication from the Messrs.

Dimock, of Uppingham, who observed it frequently building

in the thatch of a barn, in company with the House-Sparrow,

entering it by holes in the outside. This statement is confirmed

by Hoy’s experience on the continent, where he often

found the Tree-Sparrow breeding in tiled roofs, as well as in

stacks of faggots, and is further corroborated by Mr. Hewit-

* Unfortunately this last peculiarity has not been sufficiently shewn by the

draughtsman in the woodcut at the head of this article.