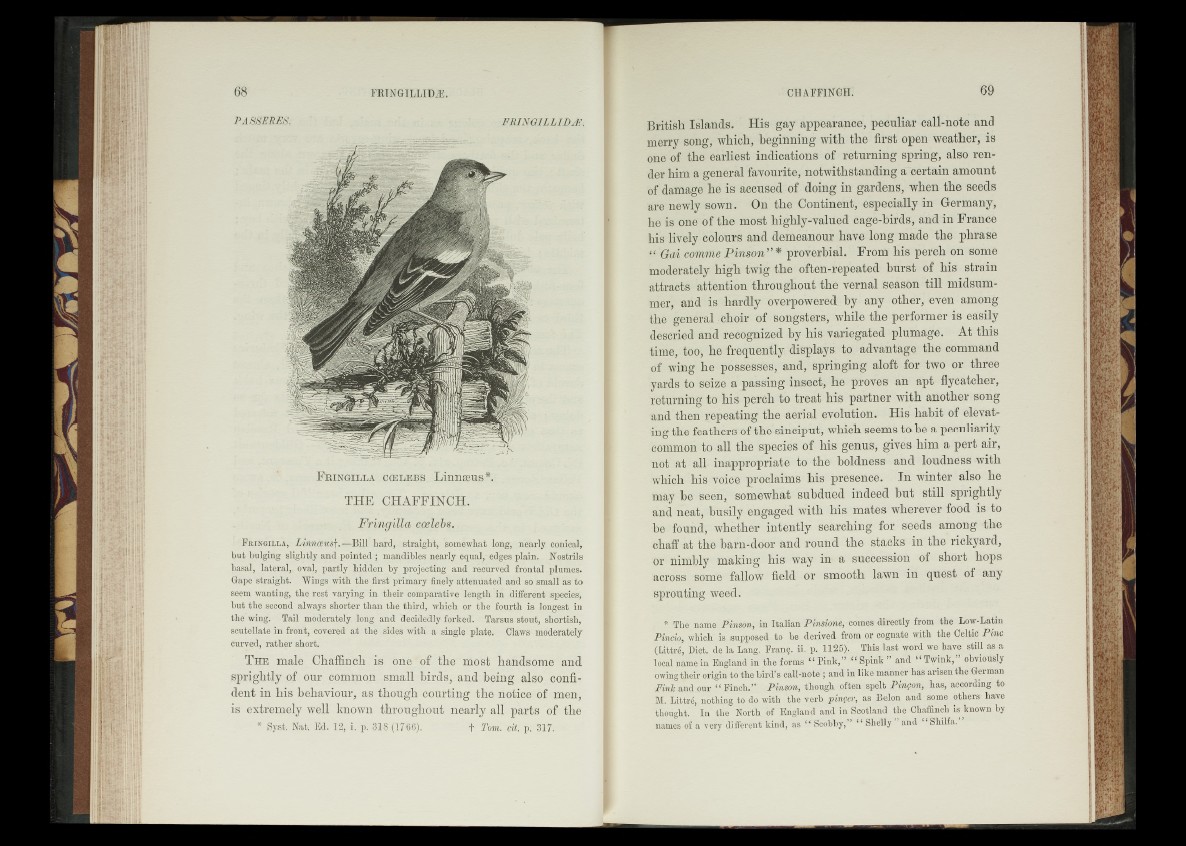

F r in g il l a c oe l e b s Linnæus*.

THE CHAFFINCH.

Fringilla coelebs.

Fringilla, Linnceus}.—Bill hard, straight, somewhat long, nearly conical,

but bulging slightly and pointed ; mandibles nearly equal, edges plain. Nostrils

basal, lateral, oval, partly hidden by projecting and recurved frontal plumes.

Gape straight. Wings with the first primary finely attenuated and so small as to

seem wanting, the rest varying in their comparative length in different species,

but the second always shorter than the third, which or the fourth is longest in

the wing. Tail moderately long and decidedly forked. Tarsus stout, shortish,

scutellate in front, covered at the sides with a single plate. Claws moderately

curved, rather short.

T h e male Chaffinch is one of the most handsome and

sprightly of our common small birds, and being also confident

in his behaviour, as though courting the notice of men,

is extremely well known throughout nearly all parts of the

* Syst. Nat. Ed. 12, i. p. 318 (1766). + Tom. cit. p. 317.

British Islands. His gay appearance, peculiar call-note and

merry song, which, beginning with the first open weather, is

one of the earliest indications of returning spring, also render

him a general favourite, notwithstanding a certain amount

of damage he is accused of doing in gardens, when the seeds

are newly sown. On the Continent, especially in Germany,

he is one of the most highly-valued cage-birds, and in France

his lively colours and demeanour have long made the phrase

“ Gai comme Pinson”* proverbial. From his perch on some

moderately high twig the often-repeated hurst of his strain

attracts attention throughout the vernal season till midsummer,

and is hardly overpowered by any other, even among

the general choir of songsters, while the performer is easily

descried and recognized by his variegated plumage. At this

time, too, he frequently displays to advantage the command

of wing he possesses, and, springing aloft for two or three

yards to seize a passing insect, he proves an apt flycatcher,

returning to his perch to treat his partner with another song

and then repeating the aerial evolution. His habit of elevating

the feathers of the sinciput, which seems to he a peculiarity

common to all the species of his genus, gives him a pert air,

not at all inappropriate to the boldness and loudness with

which his voice proclaims his presence. In winter also he

may he seen, somewhat subdued indeed but still sprightly

and neat, busily engaged with his mates wherever food is to

he found, whether intently searching for seeds among the

chaff at the barn-door and round the stacks in the rickyard,

or nimbly making his way in a succession of short hops

across some fallow field or smooth lawn in quest of any

sprouting weed.

* The name Pinson, in Italian Pinsione, comes directly from the Low-Latin

Pincio, which is supposed to be derived from or cognate with the Celtic Pine

(Littré, Diet, de la Lang. Franç. li p. 1125). This last word we have still as a

local name in England in the forms “ Pink,” “ Spink ” and “ Twink,” obviously

owing their origin to the bird’s call-note ; and in like manner has arisen the German

Finie and our “ Finch.” Pinson, though often spelt Pinçon, has, according to

M. Littré, nothing to do with the verb pinçer, as Belon and some others have

thought. In the North of England and in Scotland the Chaffinch is known by

names of a very different kind, as “ Scobby,” “ Shelly and Shilfa.