It is now generally conceded that the structure of all

animals is, as remarked by Macgillivray, in every way correlated

with their mode of life, and in no one animal more so

than in any other; but sometimes we are able to trace

clearly the connexion between a curious structure and its

results, and this is especially so as regards the tongue of

the Woodpeckers. That of the present species, with its

appendages, has been frequently figured and described, and

reference may be particularly made to the description and

figures given by the careful author just named (Br. B. iii.

pp. 57-60, pi. xv.). This organ is capable of extraordinary

protrusion, a property obtained by the elongation of the

posterior branches of its bones (the ceratohyal and apohyal),

which, after diverging and extending backwards and downwards

in a long loop, pass upwards round the back of the

head and forwards over the right orbit till they are attached

to the cavity of the right nostril.* Each of these elongations

is accompanied by a slender muscle, one end of which

is attached to the tip of the apohyal and the other to the

lower jaw, so that by its contraction the loop is straightened

and the tongue thrust o u t: another pair of muscles folded

twice round the upper part of the trachea, and adhering

thereto, are attached to the anterior part of the tongue (the

basihyal), and by their contraction the tongue is withdrawn.

The tip of the tongue is a horny point beset with a few stiff

barbs, pointing backwards. On each side of the head,

behind and below the ear, is a large elongated parotid

gland, whence a duct passes forward to the symphysis of

the mandible, and just where the tip of the tongue habitually

rests. Through this duct the glutinous secretion of the

glands flows copiously, keeping the tip constantly moist, and

thus fitted for securing the smaller insects on which the bird

* Nitzsch found that they are sometimes, but rarely, diverted to the left^ side

(Naumann, Voeg. Deutschl. v. p. 252). In other Picidee, as Macgillivray

observes (Audubon, Orn. Biogr. v. p. 542 and B. Am. iv. p. 289), the arrangement

is different. For instance in Dryobates villosus, the prolonged bones recurve

round the right orbit to reach the line of the posterior angle of the eye, while

in Sphyrapicus varius, as well as in the two species next to be described, they

extend only to the middle of the occiput.

so much feeds, while it is freely supplied with mucus each

time that it is retracted into the mouth. An examination of

the crop shews that the prey is not transfixed, as many

people have supposed, by the horny tip of the tongue, but

simply captured by the application of its slimy and adhesive

surface, though probably the barbs assist in detaching the

insects from their hold.

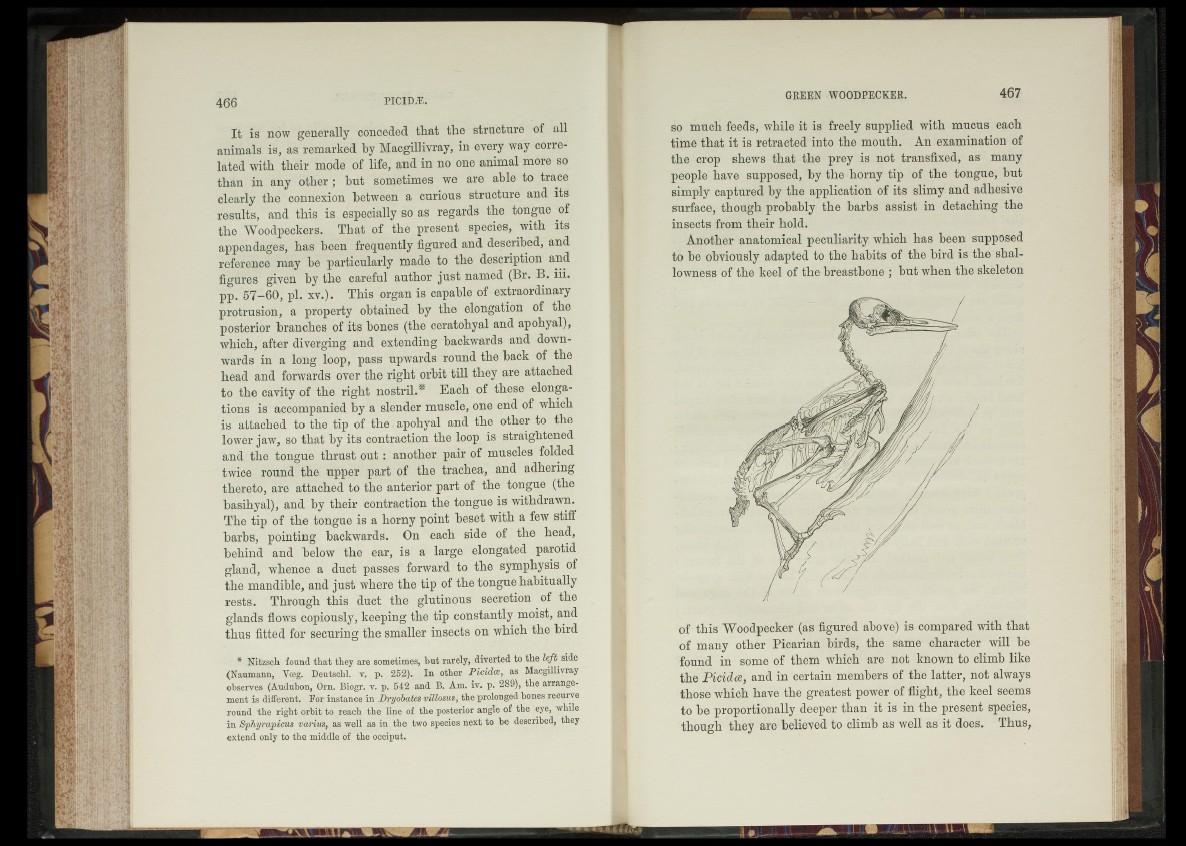

Another anatomical peculiarity which has been supposed

to be obviously adapted to the habits of the bird is the shallowness

of the keel of the breastbone ; but when the skeleton

of this Woodpecker (as figured above) is compared with that

of many other Picarian birds, the same character will be

found in some of them which are not known to climb like

the Picidce, and in certain members of the latter, not always

those which have the greatest power of flight, the keel seems

to be proportionally deeper than it is in the present species,

though they are believed to climb as well as it does. Thus,