ornithologist’s eyes ; but here it is not intended to go into

the vexed question of the comparative profit or loss of

his existence, as l’egards the gardener and agriculturist.

Very much is to he said on each side, and the bird’s best

friends will do wisely by eschewing any violent partizanship

until far more careful observations— especially by disinterested

and unprejudiced persons—have been made. It

may be freely admitted that in many instances the damage

done to pease and ripening grain is incalculable; but equally

incalculable is the service as often performed by the destruction

of insect-pests. Not only are the young, during the

earlier part of the breeding-season, mainly fed on destructive

caterpillars, but the parents, for their own sustenance

then capture, even on the wing, a large number of noxious

insects in their perfect stage*. Thus it is still a question

whether the benefit conferred is not an equivalent for the

corn and seeds stolen during the rest of the year, and it

must be always borne in mind that a very large portion of

the food of this and other species of granivorous birds is

such as could never be turned to any useful end. What,

however, are called “ Sparrow Clubs ” for the indiscriminate

destruction of this and other small birds deserve nevertheless

to be regarded with the utmost abhorrence.

The great attachment of the parents to their young has

been frequently noticed. Prof. Bell,, in 1824, stated (Zool.

Journ. i. p. 10, note) that a pair of Sparrows, which had

built in a thatched roof at Poole, were seem to continue

their regular visits to the nest long after the time when the

young usually take flight. This went on for some months,

till in the winter, a gentleman who had all along observed

them, determined on investigating the cause. Mounting a

ladder, he found one of the young detained a prisoner by a

piece of string or worsted, which formed part of the nest,

having become accidentally twisted round its leg. Being thus

unable to procure its own sustenance, it had been fed by the

continued exertions of its parents. A parallel instance had

* Particularly Phyllopertha horticola—the chovy, as it is called in East

Anglia, where in some seasons it swarms and is most mischievous.

already been recorded by Graves, who, finding a nestling

Sparrow in like manner entangled by a thread, observed

that the parents fed it during the whole of the autumn and

part of the winter, but, the weather becoming very severe

soon after Christmas, he disengaged it lest its death might

ensue. In a day or two it accompanied the old birds, and

they continued to feed it till the month of March, by which

time it may be presumed to have learnt to get its own living.

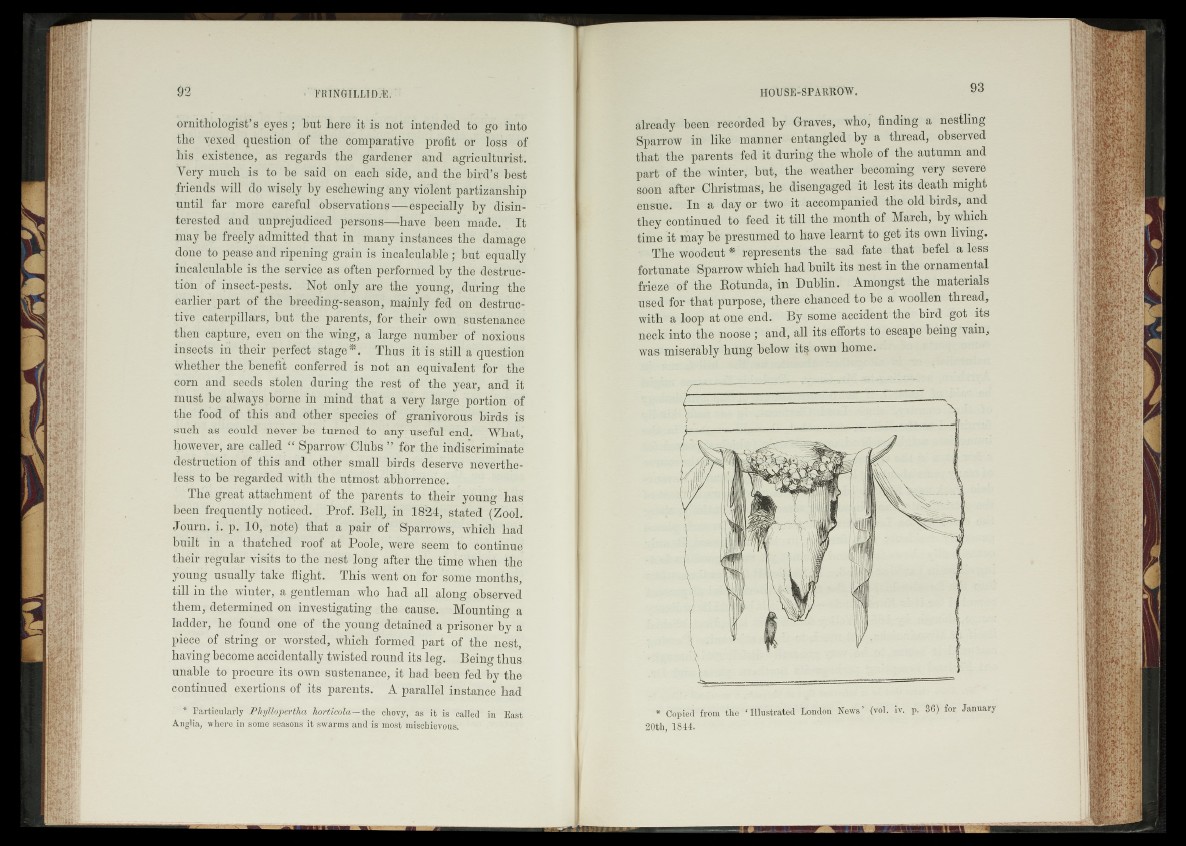

The woodcut * represents the sad fate that befel a less

fortunate Sparrow which had built its nest in the ornamental

frieze of the Rotunda, in Dublin. Amongst the materials

used for that purpose, there chanced to be a woollen thread,

with a loop at one end. By some accident the bird got its

neck into the noose ; and, all its efforts to escape being vain,

was miserably hung below its own home.

i

* Copied from the ‘ Illustrated London News’ (vol. iv. p. 36) for January

20th, 1844.